Up Next

War! What is it good for?

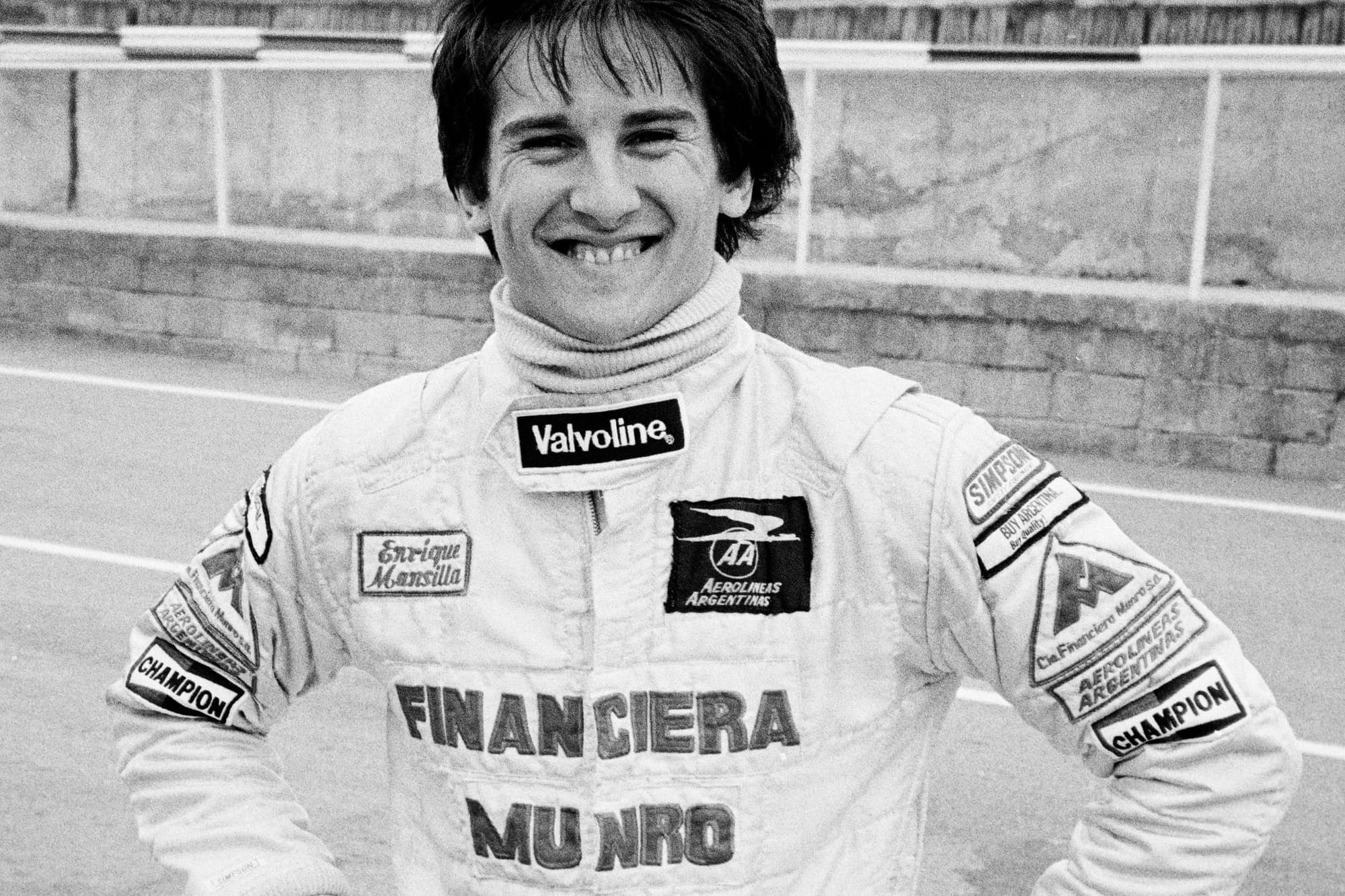

Absolutely nothing...if you were up-and-coming junior single-seater driver Enrique Mansilla in the 1980s.

That’s because his professional life at that time was ultimately defined by two separate international crises and he was an unwilling and unlucky victim on both occasions.

All images courtesy of Jeff Bloxham and Enrique Mansilla

The first, as an Argentinian national racing in the UK in Formula 3 in 1982, was the Falklands conflict, and the other was a terrifying civil war in Liberia just when he was trying to re-establish his life away from motorsport to make money for another crack at a career in racing.

His life at this time reads like a long forgotten Norman Mailer novel, full of complexity, questioning, global events and the existential wonder of ‘what ifs’.

As a driver who finished a close second to one of the all-time greats, Ayrton Senna, in Formula Ford 1600 in 1981 and then to one of the 1980s' greatest lost talents, Tommy Byrne, in F3 a year later, Mansilla is perhaps a driver who has a claim to being the unluckiest of that decade.

Quick out of the blocks

Born in Buenos Aires in 1958, Mansilla didn’t even sit in a racing car until he was 19 years of age. But what he lacked in practice as a boy he made up for as a man.

Enrolling at a local race school in 1978 after his mandatory military service had been completed, Mansilla, known universally as ‘Quique’, soon discovered he had a natural aptitude for the art of controlling racing cars.

His tutors were astonished that with no prior experience he could vanquish several others who had been karting and competing in other forms of racing for years.

As a result, he won a scholarship to travel to the UK to follow in the footsteps of other talented Argentinian racers such as Carlos Reutemann, Ricardo Zunino and Oscar Larrauri.

Showing up at the famed Jim Russell Racing School in the summer of 1979, Mansilla hit his straps quickly and thoroughly impressed then head of the school John Kirkpatrick.

Kirkpatrick is unequivocal in his praise for Mansilla, telling The Race he was “a talent who would have made a mark in F1 had he got a chance” and a driver who was “a complete natural, a bit wild at times but the speed was most definitely there”.

His first Formula Ford season in the UK in 1980 fits that summary. He ran as a consistent top-six driver but the inevitable incidents while learning a whole new variety tracks ensured he finished his first-ever racing season ninth in the standings in what was his first-ever season of competition.

It was a massive culture change for the affable kid from Buenos Aires but he relished being in the UK.

“I was in this cold, wet place and I couldn’t speak a word of English but I was happy,” Mansilla tells The Race from his native Buenos Aires.

“I just felt so at home in the Formula Ford 1600 car and I ended up winning the world scholarship at the end of ’79.”

That enabled him to enter six RAC FF1600 races but that turned into a full campaign as he dredged in money from “anywhere and everywhere”.

“I sold my cat, my dog and some fish!” recalls Mansilla.

By 1981, he was “quite ready” for a crack at the title with the factory Van Diemen team. That opportunity came after boss Ralph Firman had been impressed by his commitment when he had equalled 1980 champion Roberto Moreno’s benchmark in a hastily arranged test at Snetterton.

Offered a seat immediately, Mansilla was paired with Marlboro Mexico-backed Alfonso Toledano in a strong looking team. But as January turned to February and the cusp of the season approached, Firman wanted a word about a possible expansion of the team.

“Ralph got me in the office and said if I had anything against a third car being entered for a friend of Chico Serra’s,” says Mansilla.

“He went, ‘Yeah I’ve been recommended this guy da Silva’. I had not heard much about him but Emerson Fittipaldi was telling people he was something special.”

"‘OK, no big deal’ I thought. He’s probably just a bit overhyped. I was wrong!”

Fighting Senna (literally)

That driver turned out to be a 21-year-old karting prodigy called Ayrton Senna da Silva.

A few races into the 1981 season and several intra-South American incidents later, the works Van Diemen squad became ever more fractious.

Mansilla and Senna started to take points off each other and then matters came to a head at Mallory Park at the end of March when Senna was put on the grass on the final lap by the eventual winner Mansilla.

Words were exchanged in the paddock afterwards and Senna grabbed Mansilla by the throat. The pair had to be forcibly separated by several onlookers.

“Once, twice he hit me before in races,” says Mansilla. “The third time I knock him off. That’s when things started to get wrong. That's why at Mallory Park I did it to him the same way he did it to me many times.

“The only difference is that that this time he lost it and he came and grabbed me by the neck. So, we had an issue.”

So did Firman, who felt inclined to split them into different series that ran in FF1600 back then.

In an intriguing microcosm, Mansilla had experienced peak-Senna before it really existed. Little did he know it at the time but he was a kind of test case for Nigel Mansell, Nelson Piquet and particularly Alain Prost a few years down the line. The great man often dished it out but seldom could he take it. That was always a chink in his armour.

That 1981 season they each won a title apiece. Senna won the Townsend Thoreson championship and Mansilla the P&O Ferries campaign. While the blood pressure was up on the track their relationship thawed somewhat off it.

“Ayrton was very introverted and he wouldn’t come out of himself easily,” Mansilla remembers.

“But our girlfriends [Senna was actually married to Liliane Vasconcelos for a few years] got on and we used to cook for each other, a Brazilian dish one night and an Argentine BBQ the next. We had some fun times as well as the difficult times too.

“But you know, Ayrton had been racing for 10 years longer than me in karts. I didn’t drive a car until I was 19. Big difference.”

In light of that, Mansilla’s 1981 had been an extraordinary success and perhaps it was overlooked, not only because Senna had come with so much fanfare but also a lot more experience.

“Quique was one of those guys that was just a free spirit,” recalls Kirkpatrick.

“He knew he was good and whatever challenge he was given, he faced it and he found the answer, and I'm sure he would have found the answer in F1 too.

“When you think how closely he ran Senna in ‘81 with such a comparative lack of experience, well that just tells you how good he really was.”

But if Mansilla thought Senna might have a bearing on his career, something way beyond his control in the deep South Atlantic was brewing to affect his 1982 ambitions in an unlikely but damaging way.

The Falklands (and taking it to Tommy Byrne)

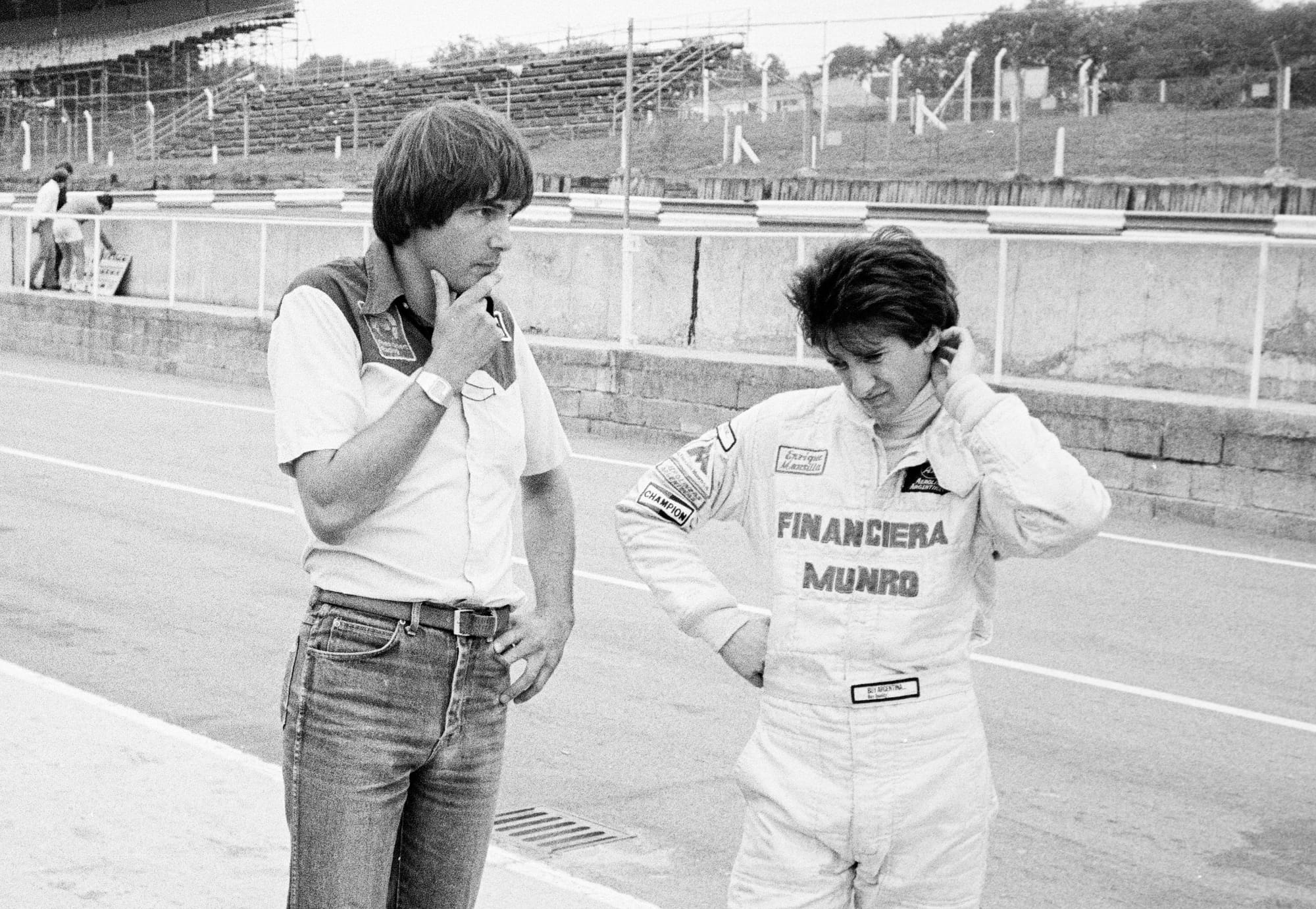

A move to F3 in 1982 with the Dick Bennetts-led West Surrey Racing squad seemed to be the dream ticket for Mansilla with an immaculately prepared Ralt RT3.

The season got off to an inauspicious start when he was disqualified for overtaking under yellow flags in the opener at Silverstone, but by the next round at Thruxton he was a close third to Tommy Byrne and James Weaver.

Mansilla, starting just his third-ever season of racing, was still ultimately processing wings and slicks, something that he himself acknowledges took him “at least five or six races to fully feel and understand”.

But this positivity, in a very strong F3 field that included Weaver, Martin Brundle and Dave Scott, was about to be checked. Thousands of miles away in the South Atlantic, an island that few had heard of before started to hit global headlines.

On April 2, just two days before the fourth round of the British F3 season at Donington Park, Argentinian forces invaded the British-held territory of the Falkland Islands and occupied the largest town on the islands, Port Stanley.

While President Leopoldo Galtieri, leader of the ruling Third Junta in Argentina between 1981 and 1982, planned to populate the island, Mansilla was preparing for free practice at Donington.

Like other Argentinian sports stars in the UK at the time, such as the Tottenham Hotspur football team's cultured playmaking duo Ricardo Villa and Osvaldo Ardiles, Mansilla was in a highly awkward position.

“It was a struggle,” sighs Mansilla. “The situation was very complicated with complicated feelings. I had friends in the Falklands and people were dying.

“War like this is crazy. Killing a lot of people and creating misery for nothing. Why? Crazy.”

While Mansilla juggled a host of new emotions, the speed eventually came and with Bennetts he was able to match the turn of pace with consistency in the summer months with four podiums. But his first of four wins that season didn’t come until August when he triumphed at Mallory Park.

By this stage, Byrne had started a largely ill-fated F1 odyssey with a decaying Theodore Racing operation and while he was away, Mansilla strung together a trio of wins at Oulton Park, Snetterton and Silverstone to thrust himself into title reckoning.

Byrne, though, in his Murray Taylor Ralt RT3, scored a crucial win at Silverstone in October. Yet, when Mansilla finished ahead of him in the penultimate round at Brands Hatch (pictured below) the two were tied on 95 points heading to Thruxton for the final race of the season under the full glare of BBC Grandstand cameras.

It started badly for Mansilla when he suffered issues with his Nicholson-McLaren-prepared Toyota engine in practice.

He qualified third behind Byrne and polesitter Brundle for the race, which was held in greasy conditions. It was a tense encounter, which although close never really caught alight as an out-and-out title scrap.

Mansilla burned up his wet tyres on the steadily drying track and it ended as it started, with second place enough for Byrne to take the championship and give himself a chance to impress McLaren with his legendary F1 test at Silverstone a few weeks later.

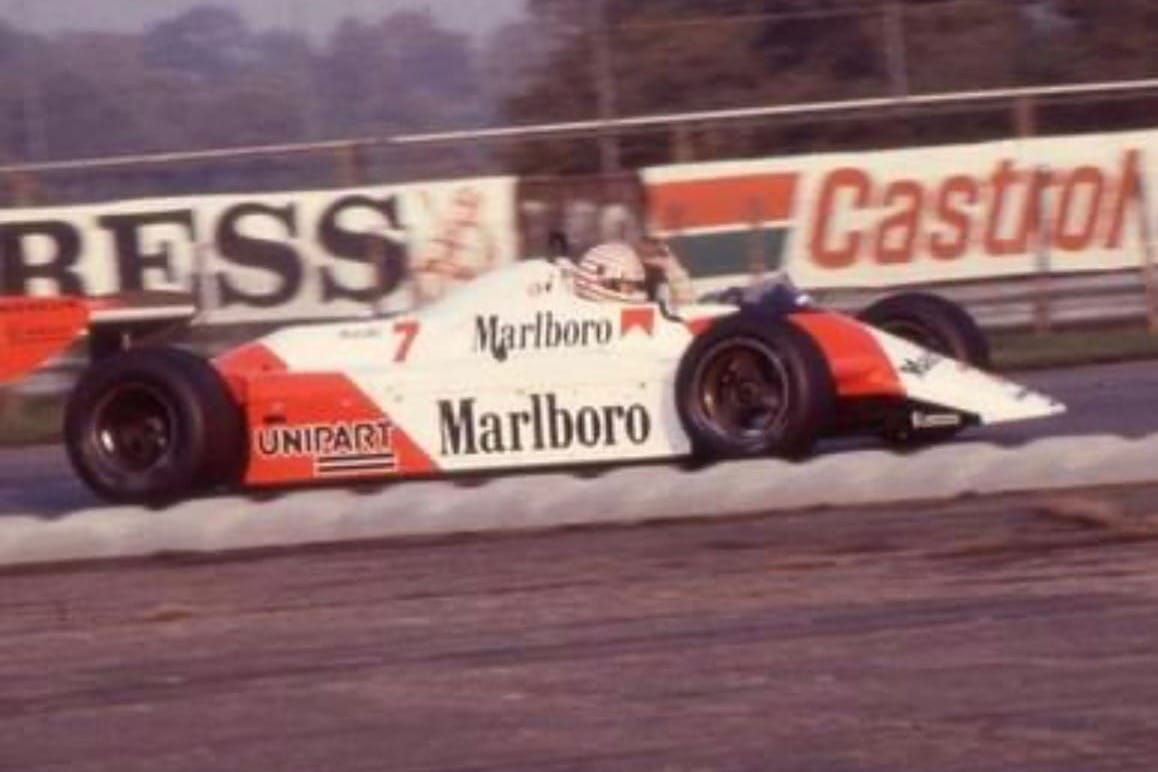

What many don’t recall is that Mansilla also got a crack at the big time in Niki Lauda’s MP4/1B, as did third in the British F3 Championship, Dave Scott, then sponsored by Marlboro.

While the test went well, Mansilla was aware that everything was coming at him very fast, and in his own words “I was testing a Formula 1 [car], it was too much”.

“So, my way of thinking then was, ‘I'm not supposed to do Formula 1, I was supposed to do testing and maybe one or two races'.”

“I got an offer,” says Mansilla cryptically, although he is talking generally about what was needed for some F1 teams at the time. “It was to do 5000 or 6000 miles of testing and two races.

The offer though was dependent on some budget being found and when Mansilla went back to a post-Falklands War homeland in the winter of 1982-83 “nobody gave a s*** about me anymore”.

“There was no money and I just couldn't do it,” he adds. “But you know, I never had an issue in England.

“I have British friends living in Buenos Aires and they didn't have any issues either. Buenos Aires is like London, very cosmopolitan and most people just recognised the war for what it was: madness.”

While Mansilla dealt with a complex situation while living and working in the UK admirably, the harsh reality was that getting money out of Argentina or any kind of serious backing to make the leap into F2 was nigh on impossible.

Kidnap in Liberia

Diamonds aren’t forever!

After a few races in F2, courtesy of Robin Herd of March, and in CART with Hemelgarn Racing in the mid-1980s, Mansilla acknowledges now that by the latter part of the decade he “wanted to get away from racing for a while” because it was “hurting me mentally and financially at every turn”.

That’s not to say Mansilla was bitter, far from it. There was, and still is, a benign resignation that circumstances beyond his control proved to be insurmountable for career progression. He’s long since been able to digest and understand the poor cards he was dealt.

If his meteoric rise in motorsport was remarkable, intense, and full of jeopardy, then the next phase of his life made all that look like a picnic in the park.

The racing world is familiar with Juan Manuel Fangio’s extraordinary shortlived kidnap in Havana in 1958, but very few know about Mansilla’s own horrendous ordeal in 1990.

Motorsport’s lesser-known kidnap story involves a harrowing ordeal for the then 32-year-old, who had elected to pursue opportunities in the mining industry, initially with a faint idea of perhaps making his fortune and re-engaging with racing.

Initially, the mining work was successful and Mansilla enjoyed his time in Liberia, a country that had abundant mineral reserves, particularly gold, iron ore and diamonds.

But by 1990 with the boom came extreme danger when the country was plunged into a brutal civil war. Incumbent dictator Charles Taylor of the National Patriotic Front (NPF) of Liberia was challenged by splinter organisation the Independent National Patriotic Front, led by Prince Johnson, and full-scale civil war broke out in many territories from the start of 1990.

Mansilla, who had a base in the country via the company that he was involved in, was aware of the dangers but they became all too real in February of 1990 when the hotel Mansilla was staying on the outskirts of the Liberian capital, Monrovia, was stormed by gun-toting operatives of the INPF.

“A bunch of rebels came into the hotel with guns and grenades and took us,” recalls Mansilla. “They thought I was American and I had to shout at them and tell them, ‘no I am Argentinian’.

“They still wouldn’t believe me and said, ‘We go to your ambassador to do something for you to help stop the war’.

“I said, ‘I don’t have an ambassador here, so am I screwed? Because I really am Argentinian’.”

“Then one guy shouts, ‘Argentinian? Ahhh Maradona! Maradona!’”

“I couldn’t believe it. Here we were in this situation and he is chanting Diego’s name. I had to laugh!”

While the few light-hearted moments sustained Mansilla, 5000 people died in the first months of the war and no resolution looked possible. For Mansilla, that meant a six-month ordeal as a captive of unpredictable soldiers of the INPF.

“It was very tough because we were in this house surrounded by guys pointing [guns] at us,” describes Mansilla.

“But we managed. I mean, amazingly. No one got killed. No one got hurt, no one got sick in all that time.

“They didn't mistreat us. We just sat there doing f*** all.

“We did listen to the radio - the BBC World Service - so we knew what was happening in the outside world but we ran out of batteries pretty quickly. But the grand prix coverage was not so good on that station!”

Eventually, Mansilla and some of the other captives were freed when it became clear to the INPF that their currency was weakening and no deals could be done.

Astonishingly, Mansilla kept working in the country for a time after that and still has some land there (as well as machinery capable of excavating diamonds).

“The country [Liberia] I love and some of the people too,” he says. “I am in contact with children of old friends that have gone now and it is nice but I needed to return to Argentina because my experiences outside of my homeland were obviously a mix of good and bad. But that’s life.”

'My story isn't over'

“You make your own luck, but you have to be lucky as well,” says Kirkpatrick.

“Whenever Quique had the opportunity he made his own luck in terms of whatever he was pursuing.

“He was quick and competitive but just so bloody unlucky that the Falklands war came along at the same time as he was making a name for himself.

“I'm sure Argentina recognised what a talent they had. But nobody dared put him in a decent car in Europe and he was just unable to generate the necessary backing to get the momentum he needed. He was so bloody unlucky and it was by no means fair on him.”

Mansilla concurs, saying that his life has been “quite something really, but I still have a good chunk of it to live too, so my story isn’t over”.

Today, he’s still embedded in motorsport in his homeland where he has run teams, acted as a consultant and organised many aspects of national series. Mansilla also heads up title-winning TCR South America outfit PMO Motorsport.

“I had a lot of fun racing Senna and loads of other quick guys,” concludes Mansilla.

“I have those memories forever, even the bad ones which are a big part of my life. It’s just the way it goes sometimes. You get lucky, you get unlucky.

“You have to accept things and just keep going. We all need to do that, right?”