IndyCar will have more power than it has for two decades from this weekend, thanks to a radical new hybrid unit totally different to the ones used by other series.

The new unit, which adds 60bhp, has been implemented mid-season and makes its debut at this weekend’s Mid-Ohio race.

The series says it’s had over 30,000 miles of testing, but we haven’t had a race weekend with it yet and the final rules weren’t published until days before the weekend, so there’s plenty to unpack and get stuck into in explaining the unit and how it might impact the racing.

Below, we’ve tried to answer the key questions, predict outcomes and highlight what to look for:

How is this hybrid different to others?

Most hybrids you see in motorsport use 'normal' lithium-ion batteries as you would see in a hybrid road car.

IndyCar’s new unit is different because instead of standard batteries, it uses supercapacitors (sometimes called ultracapacitors, one is pictured below).

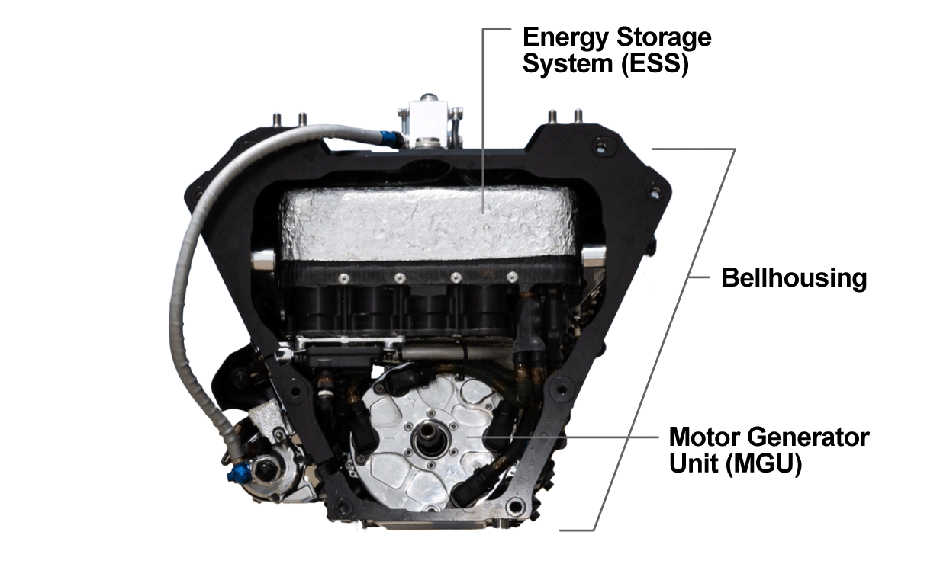

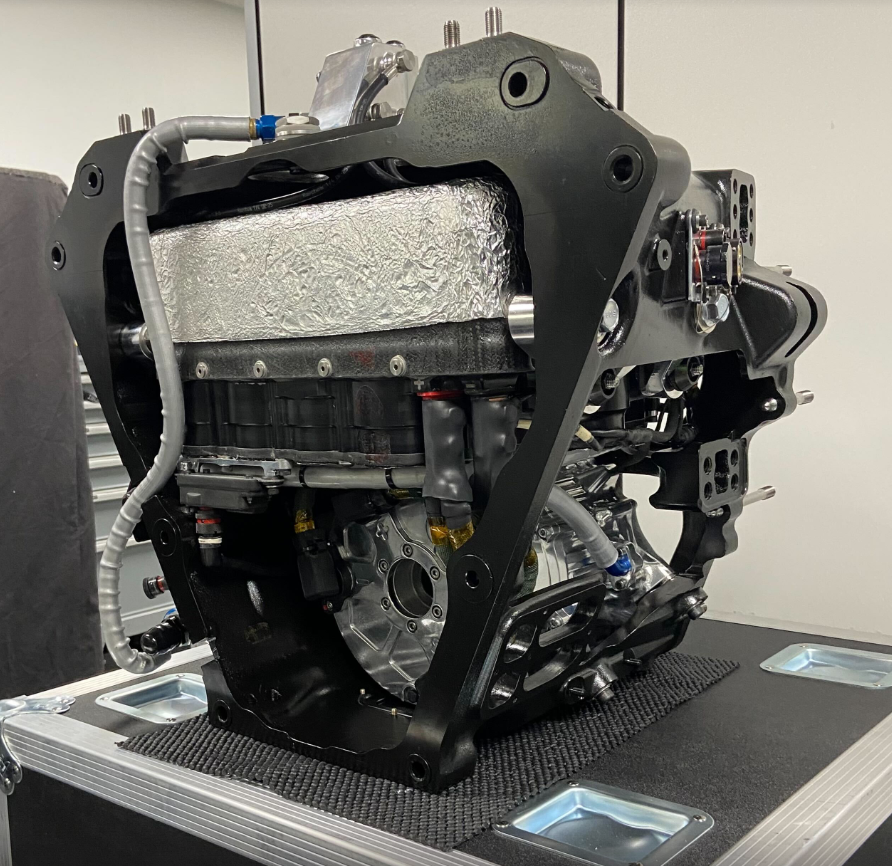

The energy storage system (ESS) in the IndyCar hybrid is made of 20 of these cylindrical supercapacitors. They are inside the light silver part at the top of the unit, pictured above.

These are different to regular batteries. They run at a lower voltage - not more than 60 volts, where an IMSA sportscar hybrid is up to 800 volts - so are generally safer, and they give off intense bursts of energy.

The downside is that they don’t store as much energy as a normal battery. That’s why regeneration is going to be so important to keep filling the battery. On track, it takes four to five seconds to fill up, and four to five seconds to drain. A Mid-Ohio, each car will be able to use 280 kilojoules per lap.

The supercapacitors are also smaller than usual batteries, which was another must for IndyCar because it is retrofitting this unit.

Chevrolet and Honda have spent 12 years shrinking and maximising the packaging of their engines as much as they can, and then suddenly they have to make room for a whole hybrid unit to be crammed in!

IndyCar has done this by putting the hybrid unit inside the bellhousing - which effectively connects the gearbox and the engine - and is pictured below.

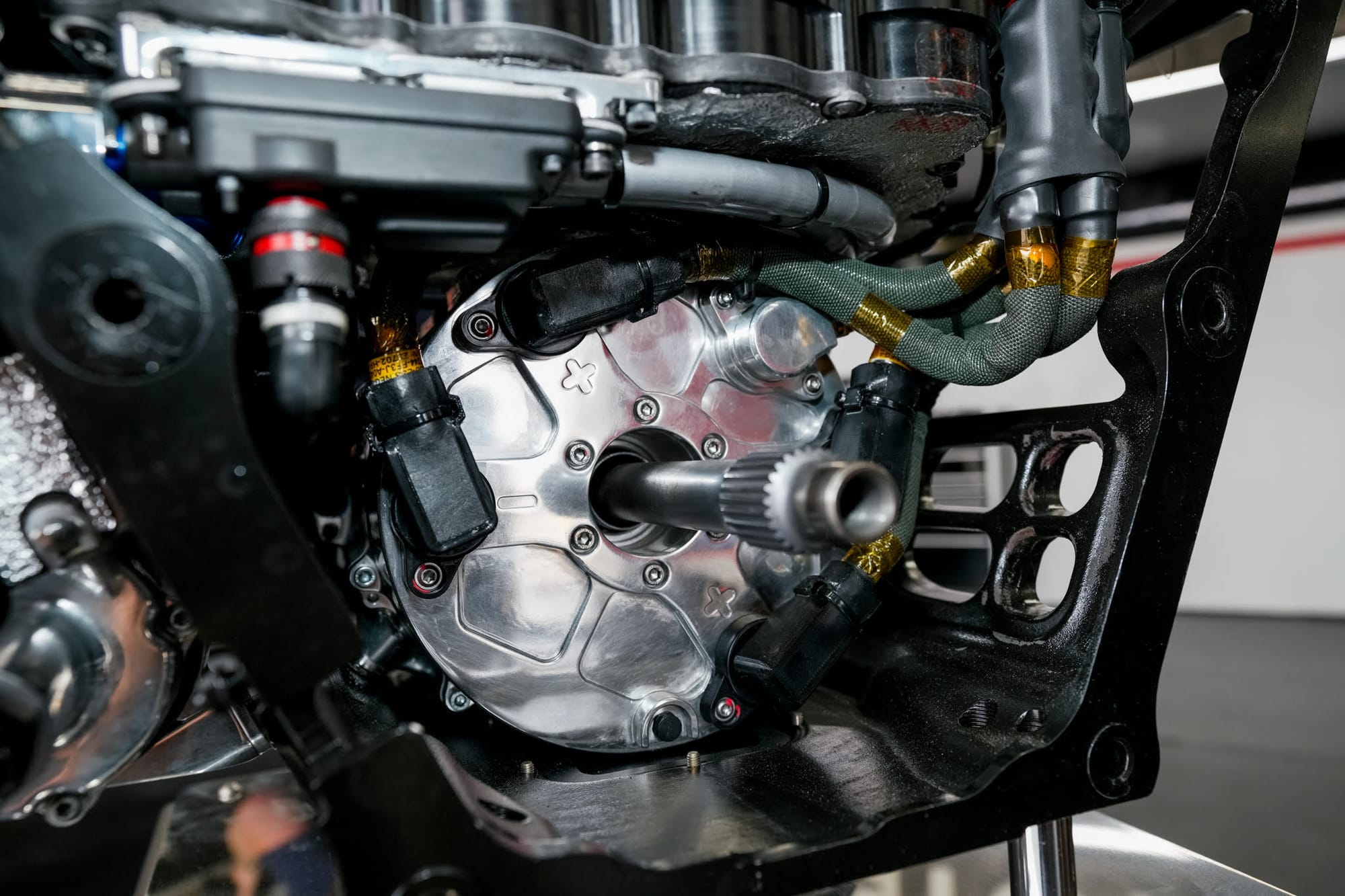

Given these challenges, it’s an engineering marvel that required both engine manufacturers to work together to develop it. Chevy and its partner Ilmor - which is responsible for the distribution of the unit and upkeep on race weekends - worked on the motor generator unit (MGU).

This takes the power from the wheels, which spins the motor in the MGU up to 12000rpm to generate electrical energy. That is sent to be stored in the ESS. The MGU also then takes the energy back from the ESS and distributes it back to the wheels as the additional power.

Honda worked on and developed the supercapacitors.

How have the teams prepared?

Of course, how much preparation each team has been able to do relies on how much resource - both financial and human - each team has at its disposal.

It’s hard not to be extremely impressed by McLaren, which has created a new role of hybrid support engineer, filled by Kenny Krajnik.

His role has been to educate the rest of the team about the unit, the dangers, the misconceptions, how to keep it functioning correctly, improving both live data and logged data and shaping the sim work McLaren is doing. He also provided The Race with a fascinating interview that helped inform this article.

I know for a fact that every team does not have a hybrid support engineer, and McLaren’s approach appears very ‘no stone left unturned’.

How has the hybrid impacted the rest of the car?

To cope with all of the heat and energy that regeneration causes, and the extra powered deployed from the hybrid, Firestone has had to make harder tyres. It’s tough to simulate the tyre at various points on the track with hybrid power being used, and because we haven’t had any race weekend action yet, it’s tough to know how the tyre is going to react.

The last time this much weight was added to the car was with the aeroscreen, which caused a massive headache for engineers because adding weight high up and towards the front of the car created some specific handling characteristics that weren’t there before, so that forced drivers to change styles and engineers to find solutions.

The added weight of the hybrid is at least low down and near the centre of the car, but the weight distribution will change. That will likely alter a whole host of set-up intricacies the engineers will need to get on top of quickly.

IndyCar has already introduced a lighter aeroscreen, lighter bellhousing and other small tweaks to bring the weight of the car down, but the car is still over 30kg heavier than it was last year and that has implications.

What do the teams not want you to know about?

When you get an abrupt no-comment as a journalist when there is new tech involved, you’ve usually stumbled across something. With the hybrid, that’s cooling.

It’s shocking that this hasn’t been discussed more in the lead-up to this race as it’s going to be one of the biggest factors of how effective this hybrid is.

It’s significant because if you abuse the supercapictors in the ESS (below) to the point where you damage them, they can’t be brought back. You’ll permanently have less power coming from the unit.

Each car is allowed to use so much hybrid energy per lap and IndyCar has done this in part to try to protect the units from breaking and causing issues this early in the cycle.

That also means the units won’t be as stressed. But it will be still possible to overheat and impact the usage of the hybrid.

The whole right-hand sidepod has been made spec between Honda and Chevrolet, so there’s not a lot inside the car itself that teams can do to steal a march here. Coolant is pumped around the unit and there’s a radiator dedicated to cooling for the hybrid. There are also special cooling plates that help.

Undoubtedly the clever teams will find little tweaks and tricks that allow them to keep the unit cooler or cool it quicker than others to gain an advantage.

Outside of the car, there are special hybrid cooling ducts in pitlane to cool the car, mostly in practice and qualifying. That being said, a spec cooling unit won’t be introduced until the Gateway race next month, so until then, each team is responsible for cooling the units itself.

If one team figures out a really efficient way to cool the unit, that might be a big gain in qualifying where there are small stoppages between the first group, Fast 12 and Fast 6.

The art of regeneration

Breaking down the new #INDYCAR Hybrid Power Unit 🛠️🏎️ pic.twitter.com/LNhyz1zJoT

— NTT INDYCAR SERIES (@IndyCar) July 1, 2024

There are two types of energy regeneration in this unit: manual, and automatic. Manual is the driver pulling a peddle on the steering wheel which will force the car to store the kinetic energy it generates while decelerating.

This manual paddle isn’t an on/off button, it’s a gradual peddle.

The other scenario is automatic regen. The driver has a dial on the steering wheel to turn, and that will activate the regen at an agreed percentage. It will be triggered by the driver lifting off by a certain amount or if they generate a certain amount of brake pressure. The teams can decide how to set that up.

Why might the driver want the regen to be taken out of their hands?

One scenario would be on low-grip tracks where maximum regen will put too much energy through the tyre and cause locking, a loss of grip, plus the likelihood of increased tyre wear.

Pulling a paddle, it’s hard for a driver to regulate - say, for example, 30% regen - for a set period. So using automatic regen can be much more accurate and in turn potentially make the car more predictable or easier on the tyres under braking.

Will it impact fuel saving?

It shouldn't massively, at least to start with.

Put simply, even with a full battery to use, you won’t be able to use the hybrid power enough to save enormous amounts of fuel. Consider Mid-Ohio, from a full-battery you’re looking at three sustained uses of boost from the hybrid, so it isn’t going to radically change fuel saving in IndyCar in its current set-up.

It will at least be better than push-to-pass in that scenario. You’ll notice in fuel saving races drivers often don’t touch the push-to-pass because they can’t if they want to save fuel and that system burns it. The hybrid is not fuel dependent.

One scenario it might have a big impact in is if you have a driver leading who is saving fuel, and a car behind which isn’t. The car ahead will be able to regen into the braking zone, and then use the hybrid power to get a better exit to try to avoid the car behind getting a run and overtaking.

Obviously, the car behind can also do this, so the advantage might be negated.

Watch out for brake bias

In most forms of motorsport, the introduction of a hybrid - usually in a new chassis, unlike IndyCar! - comes with a host of other upgrades to help manage that unit, like traction control, or brake by wire, for example.

Brake by wire is basically where the brakes are managed electronically through an ECU. IndyCar doesn’t have them.

Why does that matter, I hear you cry! Let me give you a scenario.

A driver is hard on the brakes at the end of a straight, and the brake bias has been set to reflect the car is regenerating through he rear of the car at the same time.

Only, 50 metres before the corner, the battery is full and the car stops regenerating.

With brake by wire, the car knows to shift the brake bias to account for the car stopping regeneration so that it can brake successfully for the corner.

IndyCar doesn’t have the brake by wire. So if a driver is hard on the brakes and regenerating for a corner, and suddenly the battery fills and it stops regenerating, the driver would have to manually change the brake bias to account for that. Only they won’t have time, everything will be happening too quickly to make the change.

It won’t be the end of the world if that happens, but we could see more lock-ups, drivers running wide or just failing to make the corner if that happens. It probably won’t happen that often, but it’s certainly something the teams have considered.

The driver needs to get this right

Ultimately, for all the complicated engineering and things that have changed on the car because of this new hybrid unit, it will all come down to the driver reading the situation and both regenerating and deploying in the right scenario to get the most out of it.

If the driver can’t learn how best to regenerate without losing time, when is best to deploy and work with the team to keep the unit cool and performing to its maximum, then they won’t benefit from it. And if you aren’t benefitting from it, and your rivals are, your competitiveness is going to be reduced.

"Some drivers will take to it very easily, and they'll be able to understand it and work with it,” says McLaren's specialist Krajnic.

“And I think you'll see some drivers just can't deal with it, period. They don't have the mental bandwidth to manage that throughout the lap.”

Low-grip tracks are going to be the most interesting place to watch the drivers work given the difficulties here on corner entry around the regen requirements.

And as for corner exits, if it’s low grip and the driver is struggling to get the power down, adding 60bhp from the hybrid certainly won’t help! Drivers who don’t like oversteer will have to cope with a bit more if they want to use the deployment on corner exit, while those that like oversteer might find themselves chewing through the tyres with all the extra power.

No boring stoppages for stalls!

Have you, like me, sat there frustrated at a driver spinning, stalling, bringing out a caution and then having to wait what feels like forever to get the race going again?

That’s because currently the IndyCar has no starter motor in it, and the AMR Safety Team has to get to the car and refire it with that thing that looks like a giant stick that goes under the rear wing in the back.

Worry no more! The hybrid unit is effectively also a starter, so if a car spins, it can refire without assistance.

That means fewer cautions or shorter cautions, and fewer red flags in intense qualifying sessions where there’s no time to be waiting around for a car that’s spun to be refired.

I know there’s a lot of technology to get excited about in the hybrid, but this is easily the change I’m happiest about!

Will teams that have used hybrids before have an advantage?

Many of the teams in IndyCar compete in IMSA too. The system used there is totally different so there isn’t much transferrable knowledge, but the people with experience there will at least be more familiar with the communication needed and some of the general things that happen while racing with a hybrid.

The McLaren team is the curveball. Where the IMSA teams use the simulators of their manufacturers so don’t have a lot of experience in writing simulator software and using said software to model lots of different scenarios, McLaren does because it has a high-tech sim on the Formula 1 side.

Admittedly, like IMSA, the F1 hybrid system isn’t relevant to IndyCar, but the simulation is.

“It's been super helpful to have access to the knowledge that the F1 team has from running a hybrid system for over 10 years,” added McLaren’s Krajnik.

“I would say the biggest benefit that we have realised comes on the simulation side.

"It was a pretty easy transfer, if you will, for us, because we run a lot of our simulation using tools that the Formula 1 team has used for many years, and so it already has provisions for a hybrid system in it, and all we had to do is just tweak a few things, and we were off and running right away.

“We didn't need to spend a lot of time developing the sim package.”

It will be fascinating if that makes a crucial difference and gives McLaren a big advantage.