IndyCar is sleepwalking into a disaster.

One of its engine manufacturers, Honda, wants the partner of its major rival Chevrolet, Ilmor, to build a spec internal combustion engine for the series. Confirmed in an interview with Racer, that’s a staggering admission and it shows the conflict between IndyCar’s past and its future.

Chevrolet itself has been more muted since the trigger for the ‘disaster’ element - a third (or fourth depending on what you count) delay for a hybrid unit being retrofitted to a 12-year-old engine and 12-year-old chassis.

But it appears an accepted view that, regardless of what IndyCar does next, if Chevrolet succeeds via its GM Cadillac brand in getting an entry to Formula 1 through Andretti it might withdraw from IndyCar anyway - before you even assess current issues and what it might want an IndyCar rules package to look like.

If you need a refresher on the hybrid debacle, the short version is its introduction has been delayed multiple times already, and has been again now until after the Indianapolis 500 next year.

This is mainly down to parts shortages, and production lead times, but IndyCar also hasn't decided how the hybrid will work on each track, despite the first announcement it would integrate it coming back in 2021.

It perhaps wanted to introduce hybrid power to be more relevant to automotive manufacturers, but they are favouring EVs and even though the hybrid super capacitor system is really cool in a motorsports context, it uses short, sharp bursts of energy - so it's not technology necessarily relevant to what you need on the road: range.

It begs the question, what on earth is the point of this hybrid? It's expensive for everyone, late, difficult to build, difficult to retrofit to a 12-year-old car, not that relevant to what consumers or automotive brands want and make, and it's embarrassed the two current engine manufacturers because they are the main companies developing it but now it's delayed.

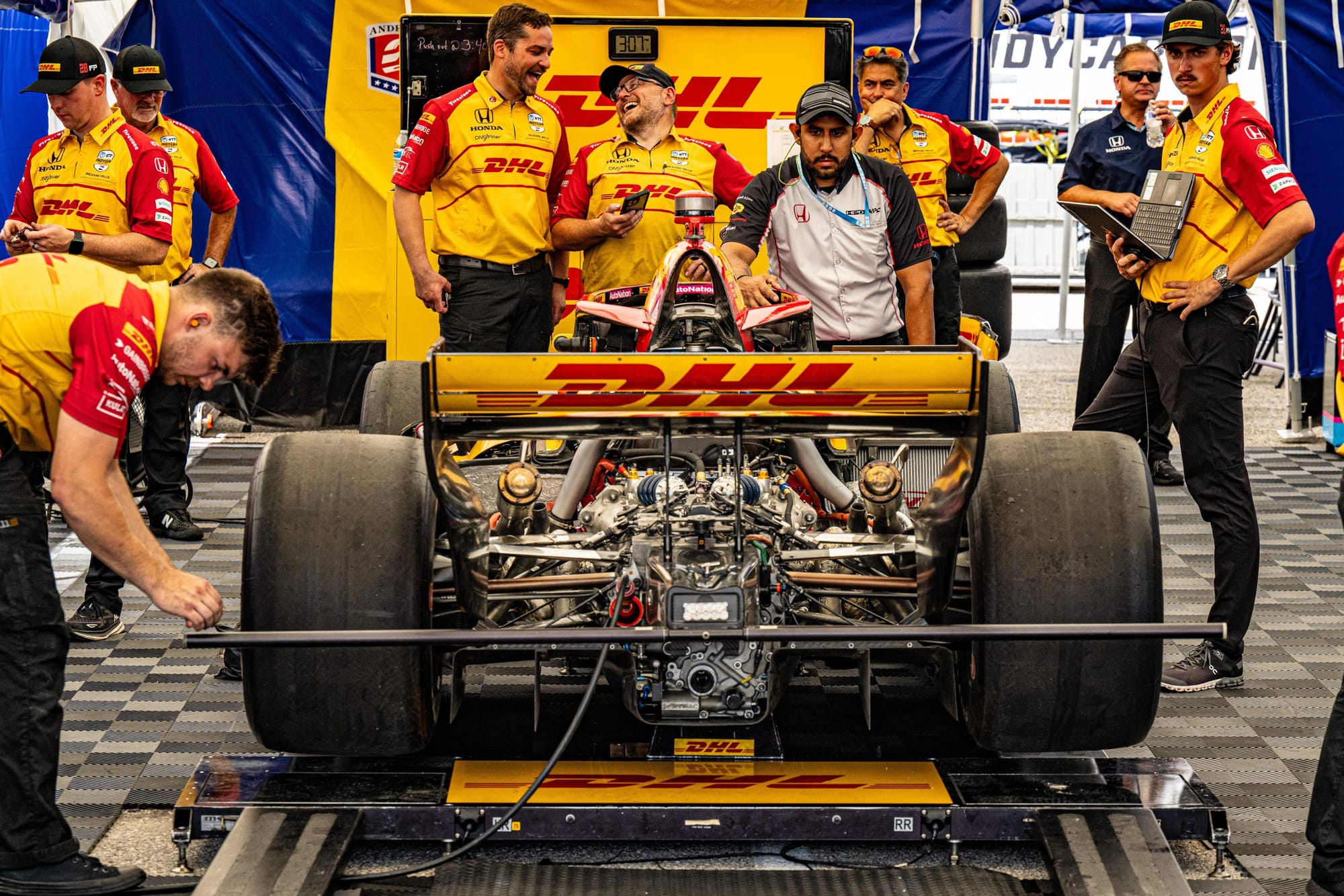

Honda and Chevrolet run engines for the Indy 500 - 33 cars at least - and 27 full-time entries in IndyCar, each with four engines. It’s a massive loss each year for each manufacturer in terms of budget, and that's before you consider how many staff it employs at the track, back at the factory, and even in places like simulation and windtunnel testing.

It has, at least, not through any official communication but through Racer, confirmed Ilmor will act as the service provider.

It's all a mess.

Speaking on the latest episode of The Race IndyCar Podcast, co-host and Indy 500 regular JR Hildebrand tells an anecdote of one of the engine manufacturers spending millions developing a piston head, something that either wouldn’t be allowed or wouldn’t be worthwhile in most other series.

It’s easy to see why costs in engine building have spiralled in the series. And in every racing life cycle a manufacturer has to weigh up if they are getting value for money. Is the money being spent in the most effective way, on the most important things? The above story would suggest not.

Here’s where it gets difficult. The genesis of IndyCar racing is the Indy 500 and Indianapolis Motor Speedway, which was designed and built as an automotive proving ground. The thought of spec chassis and spec engines is almost enough to have some IndyCar fans assembling en masse to march on city hall. Development has been at the series' core for a long time.

But at the same time, motorsport has changed. Spiralling costs almost always lead to doom and open development has in many cases been swapped for spec parts, fewer testing days, and tighter restrictions.

IndyCar itself has done some of these but, in other areas, it has allowed costs to rise. Even the parts IndyCar does allow to be developed aren’t done for the right reasons.

Millions are spent on damper programmes in IndyCar, which is fascinating for the initiated. But if you’re a general fan, do you know what a damper does, or why it affects basically the whole set-up philosophy of the car? And do you care? The millions spent on the head of a piston is further proof of this.

Dampers were never meant to be an area of development millions were invested in; they were open purely to allow teams to use older, different ones. But that loophole has never been closed even after everyone has seen the crucial battleground it has become, one on which the smaller teams can't possibly catch up.

Very few major racing series have proper engine manufacturer battles without a balance of performance system. And don’t get me wrong, I’d rather listen to cutlery scratching a dinner plate for 15 hours before ushering BoP into IndyCar.

But if you want manufacturers, you need to provide an enticing proposition and a level playing field for them to compete on. They aren't going to come in when the machinery is 13-to-14 years old and the existing manufacturers have been in place for so long.

That leads us to the chassis. I love the DW12. But, the longer it remains in use, the longer it is the same thing, over and over again, plus it’s a huge advantage to existing teams and manufacturers, given how long it has been in service.

IndyCar likes to regularly reiterate how different the car is because it's been developed so long. But at least one chassis racing at this year's Indy 500 was still in use from that original 2012 season.

It feels like IndyCar is doing the same thing - with little tweaks - over and over again. The way the current on-track product shows that elements of that have been extremely successful, but it cannot last forever.

The time has come for more radical change.

I can understand some of the leading people responsible for the series get up and go to work every morning at the home of the world’s biggest single-day sporting event and think everything is going well.

And many of the things IndyCar has done have been fantastic. Especially in the area of sustainability, with renewable diesel for transporters, more electric vehicles carrying goods for the Indy 500, Firestone's Guayule race tyre, Indy's commitment to solar power, and a renewable race fuel from Shell that doesn't get the credit or discussion it deserves.

All of these things add up to a series doing plenty for sustainability even without a hybrid adding on top. It's way ahead of many other series in terms of what is effectively a push towards net-zero and in that area it deserves a ridiculous amount of credit for how much it has achieved in such a short space of time.

That’s before you mention Penske’s purchase of the Speedway and IndyCar Series before the pandemic.

I am 100% convinced that the series wouldn’t have survived in its current state had Penske not made that purchase and not only floated the series, but helped mitigate the loss of ticket sales for the world’s biggest single-day sporting event while improving things such as the facilities at Indianapolis or the budgets available for things like marketing.

However, it’s fine to simultaneously respect and praise Penske for potentially saving the series and Indianapolis Motor Speedway while also criticising it for overseeing a lack of enough future development that could help build on the work it has done in recent years.

Chevrolet and Honda pulling out of this series - something that isn’t definitely happening, but is a very real threat in the future - would plunge it into disarray overnight, and there’s no amount of bricks or pints of milk that will solve that. Adjusting its course before either gets to a point of making that decision is crucial.

And with the chassis, you’re looking at around three years from inception to delivery. There’s no talk of that process having started for IndyCar yet, so this is where the sleepwalking comes in. Not only does it need to solve its current hybrid dilemma, it should have been working extensively on the next rules cycle due to start in 2027 last year, ideally, and not just bouncing some ideas around.

That 2027 season is the chance to course-correct IndyCar into a series not reliant on two engine manufacturers or to go in a totally different direction. It’s possible some of these ideas are being bounced around but, from what The Race understands, planning is not as far along as it could be.

DTM is a fine example of a series that's had to pivot in recent years. It just about switched concept before it went into oblivion, but it had a major manufacturer in Mercedes pull out, then BMW, and it had to basically give up everything it believed in - silhouette racing cars that were closer to F1 than GTs, with outlandish bodywork and different looks and feels - and swap that for much more homogenised GT3 category.

With a switch to a lower-cost rules package, it was able to survive and it’s hard to argue that it’s not thriving as one of the, if not the, premier GT3 competition in the world.

Homogenising is not the only route IndyCar needs to go. In either of the scenarios available it needs to take the lead and decide on its future without signing an engine manufacturer - and hope to attract one afterwards instead - but it could also go the other way and become a hotbed for innovation.

What if it opened the Indy 500 up to all-electric or hydrogen cars; autonomous ones, even? Invite people to come and test their products in the toughest race in the world. It’s not the way I’d go, but it’s another way to establish a USP.

The Le Mans 24 Hours has done that relatively successfully with Garage 56, although nothing rivalling its top class has come along yet, and the Indy 500 is arguably an even tougher test because although it is much shorter, it requires high power for long periods which is where fuel’s efficiency over electric power gives it an even bigger advantage.

Indy held a huge autonomous car race recently, harking back to its automotive proving ground roots. More of that kind of thinking could give it a big advantage over many other series. Especially as the choice is to either come up with something radical or follow the formula of other series and be more like something that already exists.

IndyCar's current USP - racing on more types of circuits than any other single-seater series - is not enough to support the series on its own or guarantee the key manufacturers remain.

Honda and Chevrolet don’t just provide engines, either. They are huge partners in TV deals and sponsor the majority of the races. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that if either left, IndyCar would not survive in its current state.

One of them is openly discussing it, and the other is facing potential F1 expenditure in the future. The warnings are clear for all to see and something must be done.

That's not to say IndyCar should choose the next rules based on what Honda and Chevy want because pandering to manufacturers isn't always the best way forward. But finding a formula that would attract any engine manufacturer needs to be the aim.

Simply continuing to do the same thing over and over again, tweaking it slightly, is not what IndyCar needs anymore.

It’s time for revolution. But no-one seems to be able to agree on what you do next.

That’s where strong and decisive leadership comes in.

The fact we’re in this position - with a three/four-times delayed hybrid unit costing millions to develop, which the series still hasn’t decided how to implement, and a plan to rush it in mid-season in 2024 - shows that the current leadership is not doing a good enough job regardless of the external factors that have impacted the series in recent years.

IndyCar needs to be better. And it deserves better.

But most of all, it needs a clear direction and development route.

Many series, like DTM and top-level sportscar racing, have had to pivot - either to satisfy manufacturers, cut costs, maybe both - in order to survive.

Things might have been good for the series in recent years, but IndyCar will only be great if it plans further ahead and solves its identity crisis.