Up Next

So remarkably terrible has Alpine's start to the Formula 1 season been, it came as minimal surprise that major exits on the technical leadership side and a reorganisation were announced immediately after the Bahrain Grand Prix.

True, tech director Matt Harman and aero chief Dirk De Beer are understood to have tendered their resignations even before the Bahrain humiliation.

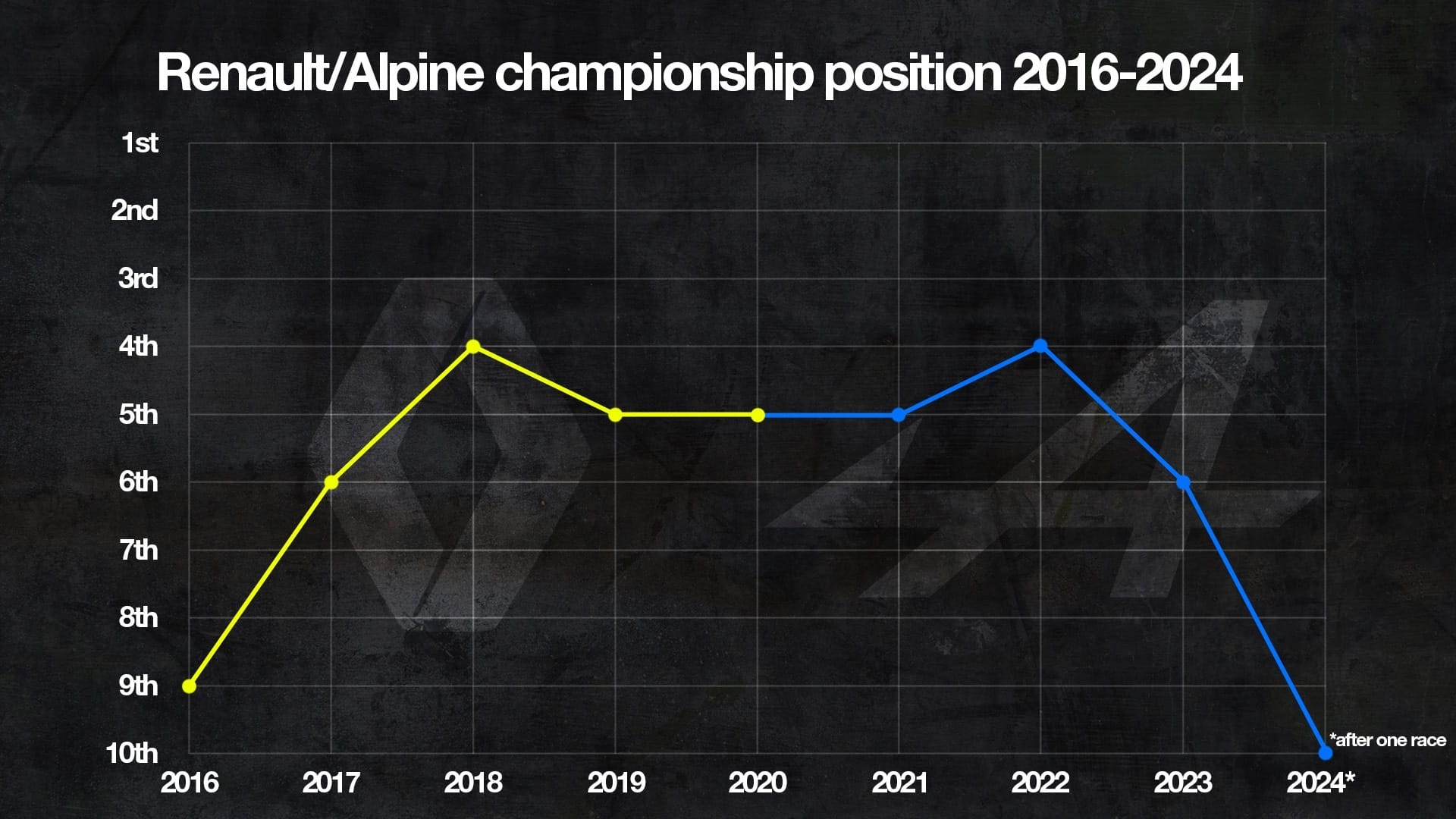

But the combination of that humiliation and yet another upheaval when it comes to the leadership positions inevitably comes as another blow to the credibility of the Group Renault-owned team - which is now in its ninth season since buying back the Enstone team ahead of the 2016 campaign.

The latest reshuffling has settled on a tech structure headed up by three technical directors: Joe Burnell on the engineering side, long-time race engineer Ciaron Pilbeam on the performance side, and former Williams F1 aerodynamics director David Wheater on, naturally, the aero side.

There's only so much of a short-term - much less instant - impact a new tech leadership can make in F1, but the urgency in having the new structure pay off is obviously high given Alpine's current performance is untenable.

Worse than 'difficult'

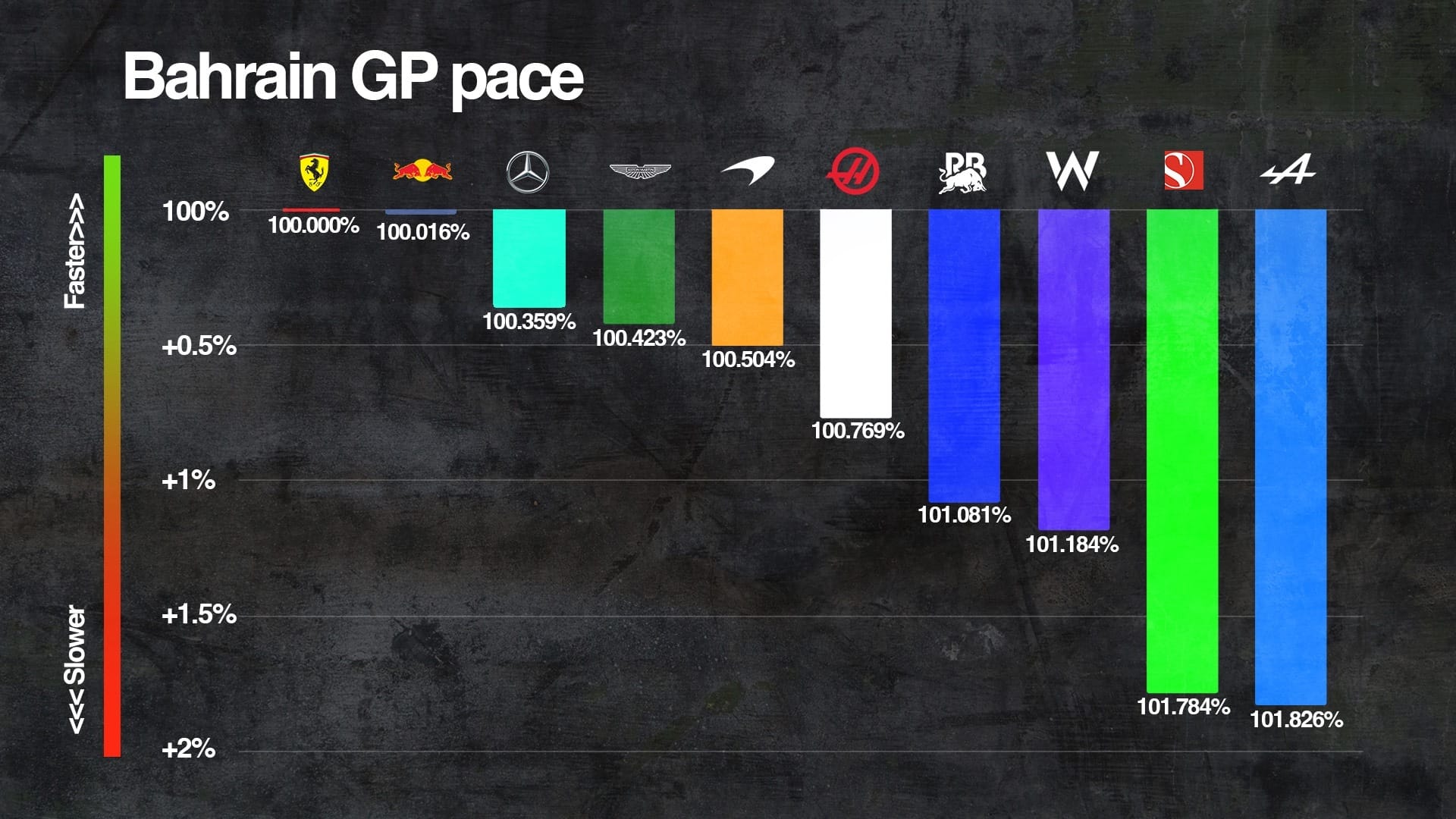

Famin admitted at the launch of the Alpine A524 that “the start of the season may be difficult”, but having the slowest car in both qualifying and race trim in Bahrain was a major blow.

There are multiple problems with the car, first and foremost the fact it is overweight. There is talk of it being 11kg over the 798kg minimum weight and although Pierre Gasly said after qualifying “it's not as bad as you mentioned” when that figure was put to him, he did confirm it was a problem.

The weight problem is primarily down to the monocoque failing the side-impact test.

The monocoque was designed with weight-saving measures incorporated in the internal structure where there is an amount of empty space among the carbon fibre. Simulations said the design was strong enough, but it’s understood the monocoque failed the test emphatically.

As a result, it has been reinforced - and that has come at a significant weight cost.

The car is also weak in terms of traction and lacks downforce, particularly at the rear, as a result of missing aerodynamic performance targets.

There’s also the problem of the power unit deficit, reckoned to be around the 15-20bhp mark, which remains a weakness despite changes in the 2024 car designed to limit what are called “parasitic losses” and ensure the power is used as efficiently as possible. This includes a change to the exhaust tailpipe design.

This added up to a car that was 1.6s off the pace in qualifying, putting Alpine firmly at the back.

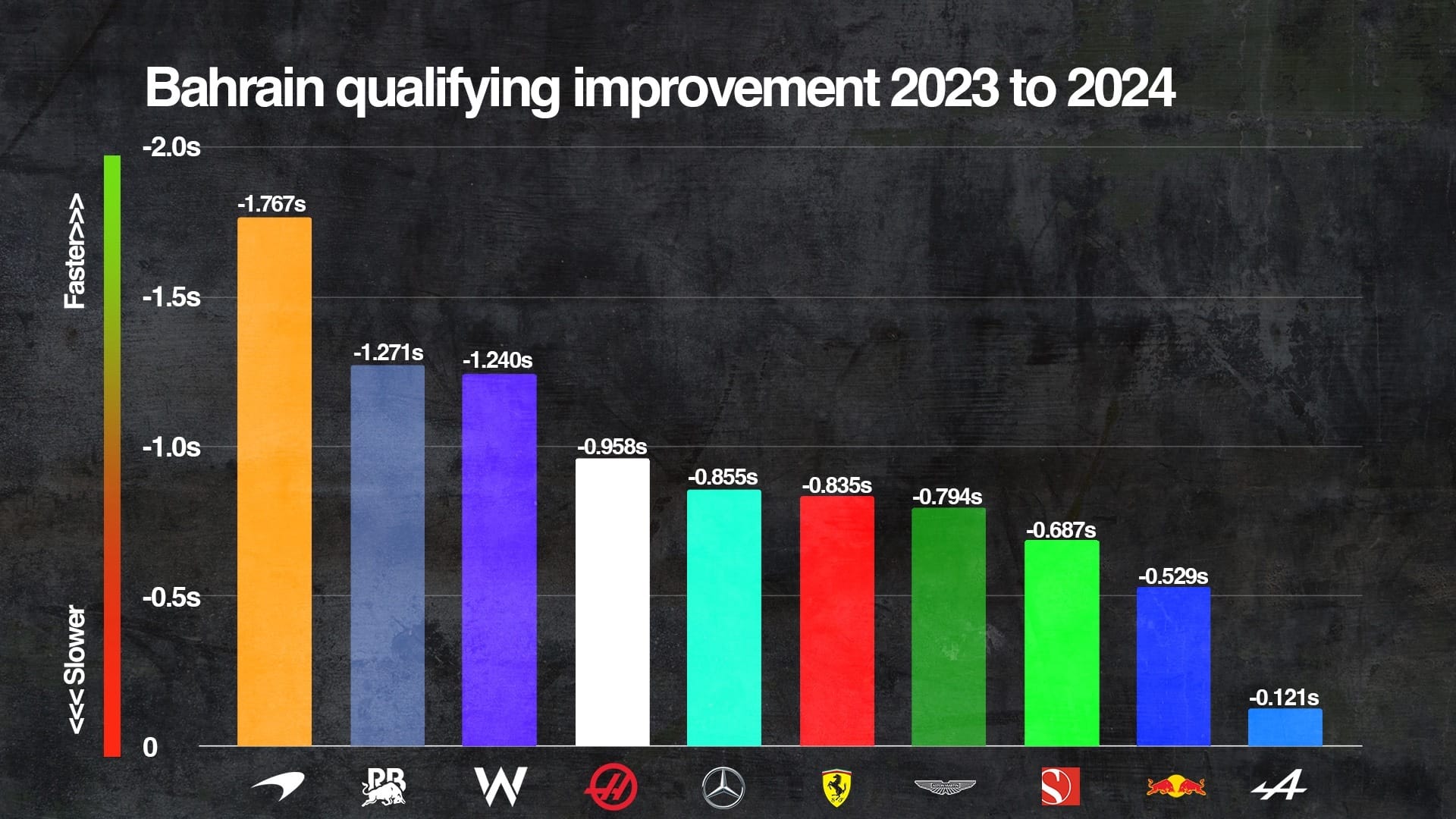

Tellingly, it made the smallest step of any team from year to year based on Bahrain qualifying pace, with its best lap in qualifying this year just 0.121s quicker than in 2023. By comparison, McLaren was 1.767s quicker.

The Woking-based team is the shining example of just how good a season can end up even when it starts terribly - and it is hard not to notice that Alpine has now followed McLaren's lead in its three-pronged new technical structure.

No quick fix

But there's no expectation of a McLaren 2023-style turnaround here - given there’s no obvious technical breakthrough that’s waiting round the corner. Instead, Alpine is talking only of making gradual progress with an upgrade expected to appear at some point after the early-season races.

The one hope is that the much-vaunted change in concept, which is focused on modifications to the way the suspension works, has unlocked significantly more development potential. But the jury is still out on whether the team really has enough understanding of how the aerodynamics and the mechanical platforms interact.

The other tiny ray of hope is that Bahrain has traditionally been a poor track for this team. It certainly plays against the car given it’s a heavily traction-dependent circuit that rewards power. In the high-speed section encompassing Turns 5 to 7, the Alpine was probably at its best in Bahrain. That means it is expected to be slightly less terrible in Jeddah this weekend.

While the team and drivers presented a ‘business as usual’ front in Bahrain, the disruption caused by news of Harman and De Beer having resigned leaking had a destabilising effect - especially give the team at the track wasn’t aware of it until the news had broken in the media.

While it’s not as devastating a bombshell as what happened around the Belgian GP last year, when team principal Otmar Szafnauer and sporting director Alan Permane were ousted, the level of disruption is obvious.

More than just a misstep

It’s clear it’s now going to be a long way back for Alpine. Given this year’s car is also the platform for next year, realistically it's now working towards 2026 and the new regulations if it’s to take a significant leap forward.

But the doubts about majority owner Renault’s commitment to the team and whether it really has the resources and facilities it needs to become a frontrunner, as a works team should be, remain. The terrible start and technical departures only serve to add to this feeling.

After all, this is now the 10th season since Renault re-acquired the Enstone team to return to F1 as a works operation. The failure of the initial five-year plan, and the subsequent 100-race plan announced by then-Alpine CEO Laurent Rossi, gives the impression of a team in a constant state of flux.

There comes a point when there have been so many team bosses and technical leaders that you have to look to institutional and ownership problems rather than shortcomings of individuals. It’s unclear whether Harman and De Beer felt they didn’t have the necessary resources and facilities for the team to work, but their departure inevitably revives memories of former chief technical officer Pat Fry saying “I didn't feel there was the enthusiasm or the drive to move forward beyond fourth” after moving to Williams.

Famin is spoken of highly for his work ethic, internal communication and sincere attempts to understand all the various departments within Alpine F1 and push for constant, all-round improvement. Whether he has the autonomy and resources he needs to do that is another question.

This has often been the problem with Renault’s F1 teams, a lack of support and not allowing the kind of autonomy that allowed it to enjoy so much success under Flavio Briatore in 2005/2006 when it won back-to-back championships.

What happens next is a severe test of Renault’s credibility and whether the Alpine F1 project will ever get on the right path. Given what’s happened since 2016, it currently feels like another step in the endless cycle of midfield success, regression then leadership changes that leads nowhere.

The only way Alpine can convince the watching world it is something different is by hitting the ground running in 2026 after these changes.