When we asked The Race Members' Club to submit questions for The Race F1 Podcast recently, Jamie Stark's question about Michael Schumacher's disappointing Formula 1 comeback with Mercedes in 2010-12 prompted such a good answer from Mark Hughes that we asked Mark to get writing on the topic too...

The questions around Lewis Hamilton’s performances as he heads into his first season at Ferrari as a 40-year-old have inevitably led to comparisons to Michael Schumacher in his comeback years 2010-12.

After retiring at the end of 2006 still apparently at the top of his game, Schumacher was 41 when he returned with Mercedes in 2010. In his three subsequent seasons, we only ever saw an occasional glimpse of his heyday phenomenon.

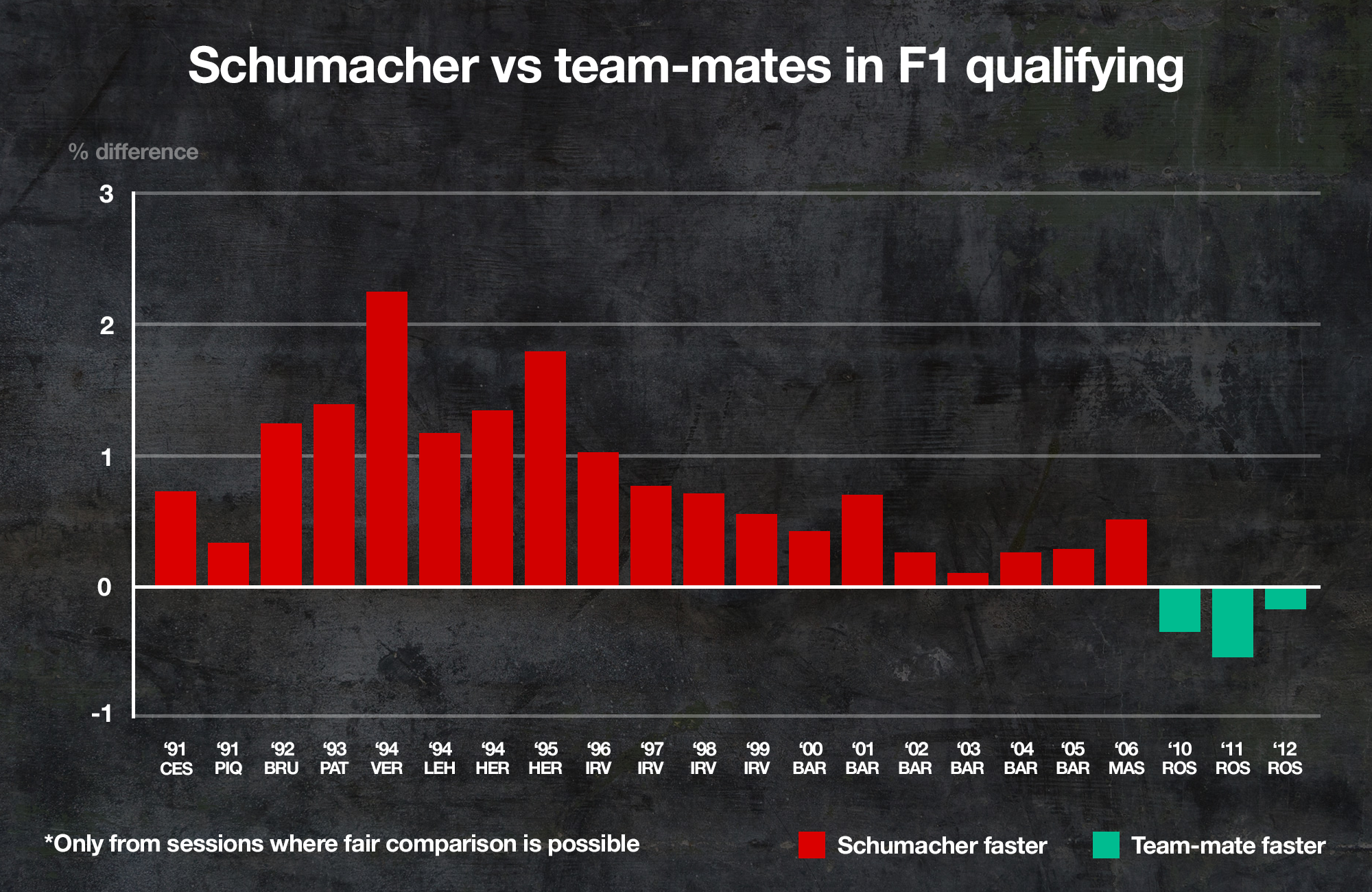

A (penalised) pole in Monaco in 2012 and a single podium (in Valencia the same year) were all he really had to show for three years in which he was soundly beaten by team-mate Nico Rosberg, 16 years his junior. Given that the Mercedes cars of 2010-12 were not absolute frontrunners, he did a more than competent job. But he was just a pale shadow of the colossus of old.

The general assumption was that the years and the three-season lay-off had taken their toll. Perhaps there was an element of truth in that. But it’s a simplistic and reductionist account of exactly what happened. There were several factors working against him.

The motorcycle injury

In February of 2009 Schumacher’s attempt at becoming a motorcycle racer ended with him falling heavily on his head at the Cartagena track. After falling from the bike at around 130mph and being thrown into the air, he landed (in a gravel trap) head-first and lay unconscious for some minutes. It was reported at the time that a hospital check-up had revealed no injuries.

This was false – as his personal physician, the late Dr Johannes Peil revealed a few months later at a press conference in Switzerland explaining why Schumacher had been forced to turn down the opportunity of deputising at Ferrari for the injured Felipe Massa during the latter half of 2009.

This article was first published in The Race Members' Club on Patreon - join us there for early access to many of our website columns plus exclusive extra content, ad-free videos and podcasts and chances to have your questions answered in our podcasts

That comeback had been thwarted because of the pain Schumacher was suffering in his neck after testing the Ferrari at Mugello. This was part of the after-effects of the motorcycle accident and came from, as Dr Peil explained, a tear in the left-hand-side ligament or tendon linking the base of the skull to the neck.

This was seven months after the accident and although that particular injury would in time heal and allow Schumacher to make his 2010 comeback, the full extent of the other injuries revealed by the doctor made it clear how the tendon tear was just a minor part of the story.

“He had a serious injury to the seventh vertebra of the neck, a fracture of the first left rib and a fracture at the base of the skull, roughly the size of a thumbnail but in a place supporting the whole weight of the skull,” reported Peil.

In 90% of cases, this in itself would be a fatal injury. It was suspected the only reason that wasn’t so in this case was the strength of Schumacher’s neck from his long career in car racing.

“There was also a hairline fracture on the left side of the skull.”

Peil had shared a concern with Schumacher that any heavy accident in the Ferrari risked further damaging this critical part of the skull before it had built up full strength, which risked long-term injury or even paralysis.

The physician went on to detail that one of the two main arteries (the left one) to Schumacher's brain had been severed and that the other one was damaged. Although the arteries were repaired, such injuries invariably bring after-effects. Typically, the neurological damage caused leads to reduced capability in certain high functions. Although the body has a great facility for repairing such damage, effectively using ‘blank’ neurons to replace the destroyed ones and reprogramming them, the specific skills those neurons controlled may not necessarily recover to the level attained before the damage. Typically, such recoveries are fuller in younger people but Schumacher was 40 at the time of the accident.

As we’ve outlined in these pages before, we don’t know the precise physiological mechanism which makes one driver naturally faster than another as it is so under-researched. But we know that tests conducted by Ministry of Defence contractors in trying to target suitable candidates for fighter pilot training suggest that physical sensitivity to rotation and yaw (applicable in both fighter jets and racing cars) originates in sensors located in the lower spine which relay sub-consciously (with zero reaction time as it is not part of the body’s reaction circuitry) to the middle ear.

If this is indeed the case, it’s not so difficult to imagine why post-bike-injury Schumacher may not have been quite the driver he had been.

Even at his peak, Schumacher’s reactions were notoriously average, as was repeatedly affirmed in tests at Ferrari. “They were about the same as mine,” revealed Ross Brawn with a smile.

It was with these reactions that he broke the record books of F1 success and established himself as one of the greatest of all time. So the idea that any difference in reaction times from 37-year-old Schumacher (in 2006) to 41-year-old Schumacher (in 2010) was responsible for the reduction in his performance seems unlikely.

No tyre war

At the end of Schumacher’s second career, during the Abu Dhabi Grand Prix weekend, I interviewed him about his three-year comeback. He made the expected observations about how he’d not been able to help the team deliver him a competitive car.

He talked about how his final season was the most competitive of the three, but how he was struggling to find the motivation to keep trying to find more. I remarked to him that standing trackside and watching him, he didn’t look to be driving in the same way as in his previous time, that he no longer seemed to be pivoting the car on the edge right at the beginning of the corner and making no further inputs, but instead was just braking late and aggressively, then sorting out the moments with his car control.

He replied with: “People say I like oversteer. I don’t. I can handle it and drive it but I don’t want it. With a neutral car you can have it sliding from turn-in to exit and all the time you can just drive on the limit of the four tyres’ given grip, and that’s what I’m always looking to achieve. I had cars that did that. With a little input you could make it go the way you wanted it to go. I haven’t had that since I came back.”

In hindsight it was rather like listening to Max Verstappen explain why he couldn’t get the early-season Red Bulls of 2022 and ’23 to go significantly faster than Sergio Perez, albeit with a significantly faster team-mate than Perez with which to compare. In both cases the cars, in imposing a restriction on their preferred way of driving, were placing a false ceiling on their performance.

Partly that was down to the traits of the Mercedes cars he was given to drive. The team had fallen behind on R&D during the near-collapse of the team during Brawn's fairytale 2009 season and the subsequent resource restriction agreement (which Mercedes initially took much more literally than Ferrari or McLaren) and the designs were flawed. But it was also about the control-spec Pirelli tyres.

In his time there during the tyre war, Ferrari had been the only major team contracted to Bridgestone, with rivals Michelin providing the rubber for Ferrari’s main competition. Bridgestone, Ferrari and Schumacher were at this time closely entwined. Schumacher was developing not just the car but the tyres which enabled him to drive in his preferred way. He was in essence enjoying tailor-made tyres, rubber developed just for him.

This isn’t to suggest that he wouldn’t have been super-successful in a control tyre era; he had after all won championships in the past without this advantage. But it definitely added to his advantage – and it had been taken away by the control tyre era which he found as he returned.

A big part of his advantage during Schumacher’s great years had been his amazing facility to lap flat-out for an entire stint.

“He would do 76 laps looking like an accident about to happen,” says his former team-mate Eddie Irvine.

“It was insane how he could do that. You give him an unbalanced car and he could just find a way around it; it didn’t really matter. That 1996 Ferrari was possibly one of the most pitch-sensitive cars of all time. It was horrible. But he just had the feel to adjust himself around it.”

That was a redundant skill in the Pirelli era. The tyres could no longer withstand being raced flat out. Instead, drivers were driving 2-3s off the pace just to get the stint lengths required for the optimum strategy. The returning Michael raged against it, saying after a 2012 Bahrain Grand Prix team-mate Rosberg won, “The main thing I feel unhappy about is everyone has to drive well below a driver’s, and in particular, the car’s limits to maintain the tyres.

“I just question whether the tyres should play such a big importance, or whether they should last a bit longer, and that you can drive at normal racing car speed and not cruise around like we have a safety car…

"Formula 1 has always been a meritocracy; in the end the best engineers and drivers will always succeed. I just think that the tyres are playing a much too big effect because they are so peaky and so special that they don't put our cars or ourselves to the limit. We drive like on raw eggs and I don't want to stress the tyres at all. Otherwise you just overdo it and you go nowhere."

Again, just as with the way the control Pirellis and their dislike of combined braking and cornering put a limit on Schumacher’s ability to find laptime in qualifying, so these endurance traits were restricting him on race day too.

Quite how all these factors combined to make Schumacher’s comeback less great than it might have been can’t be known. But we can be pretty sure he didn’t go from one of the greatest of all time to an also-ran just because of the passage of 36 months.