Up Next

Liam Lawson will see his promotion to Red Bull as the opportunity of a lifetime - and so he should. A seat in Formula 1's top team after just 11 grands prix will seem like the stuff of dreams. But being paired with Max Verstappen can also be the stuff of nightmares.

Pierre Gasly, Alex Albon and Sergio Perez could all tell him what it's like to have your confidence undermined by being directly measured against the scale of Verstappen's ability every couple of weeks. How that can feed upon itself and take you on a downward spiral that just exaggerates your shortfall.

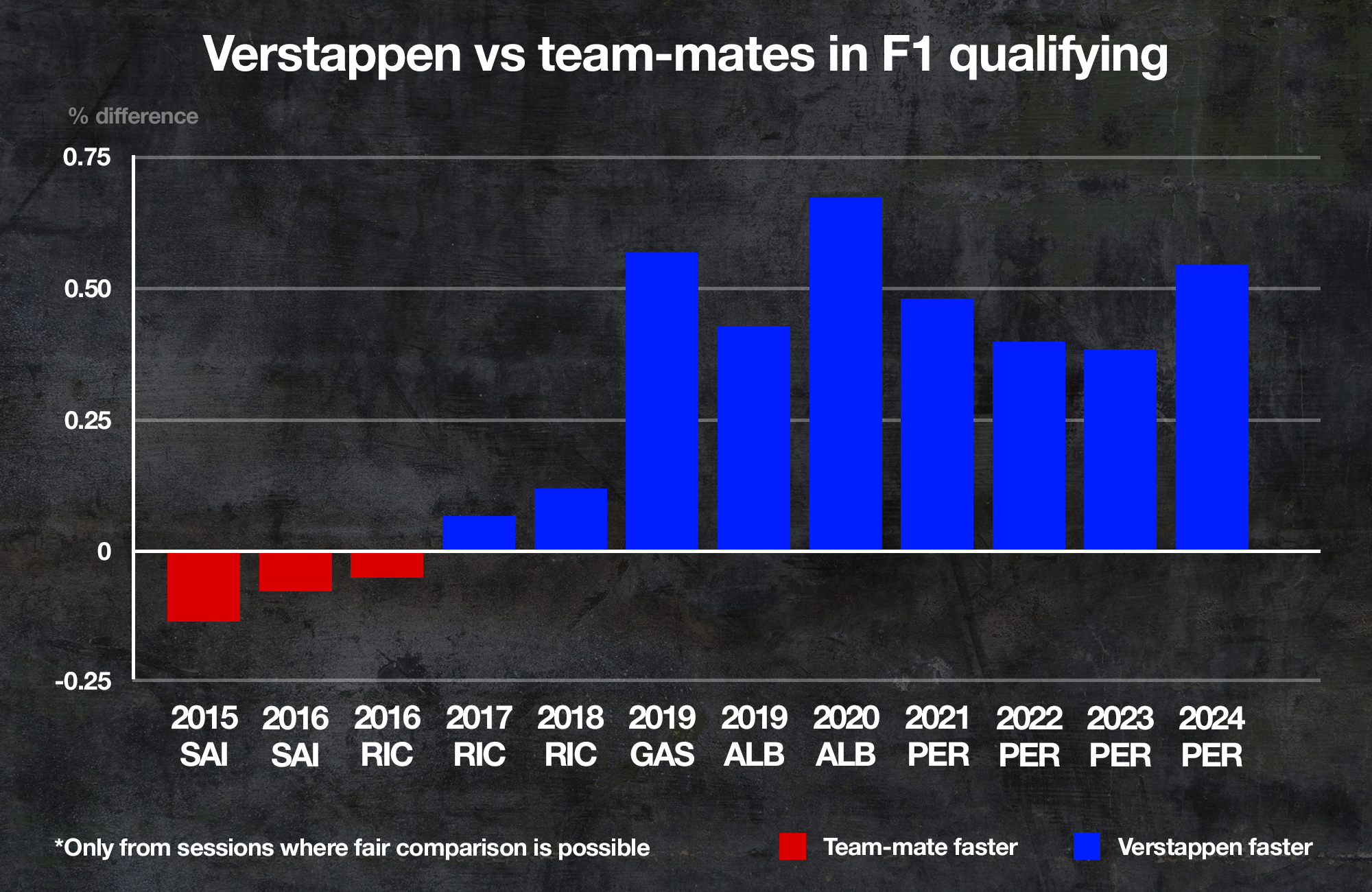

It's not that it's impossible to compete with Verstappen as a team-mate - Carlos Sainz and Daniel Ricciardo both made a fair fist of it - but Lawson is stepping into probably the toughest gig in F1.

At the very core of Verstappen's amazing ability is how he feels the car on the entry to a slow corner. "When you look at the big difference between him and his team-mates," said Christian Horner in 2023, "it's never really been in the high-speed stuff - Pierre Gasly, for example, in a high-speed corner would be as quick, if not quicker, than Max.

"But it's that whole braking phase into a slow corner and his total confidence and ability to deal with a rear end that is a bit loose.

"Look at Turn 3 in Austria, for instance, which is always a standout corner for him. If the rear of the car isn't completely planted, because of his sensitivity and feel - almost like a motorcycle racer - he can effectively be right on the edge of adhesion on corner entry and if the rear is moving around it doesn't bother him.

"What he wants is a really positive front and he will deal with the rear."

This has had an impact upon the direction of travel of Red Bull's aero development.

Not in the sense that it has been deliberately tailoring its car concepts around the specific skills of Verstappen; there probably isn't any team advanced enough to be able to do that. It's been more about the development direction of each car, as Verstappen has found more laptime from a certain direction.

More on Verstappen and Lawson

- What is a pointy front end?

- Where Red Bull thinks Lawson will be closer to Verstappen

- What saved biggest Verstappen 2024 wobble

So the team has followed that course as it has developed each car within the constraints of its design. Twice - once in 2020 and again in 2024 - it has tripped them up.

At the end of the 2020 season, technical director Pierre Wache explained how this manifested on that occasion. "Max's talent was a contributory cause to the problem we had," said Wache. "He has an ability to control instability that would be impossible for some others.

"We know that sometimes making a car on the edge in this way can create a quicker car. So we went in this direction and Max was extracting laptime from it and so we kept going in that direction.

"But it was only because he has so much talent that he was still getting laptime from it as we kept going. We realised after a while that we had reached the ceiling with the car in this way and also you saw with the other drivers, with Pierre and Alex, they struggled to extract the best from it.

"We had gone too far in this direction. The system is so big, to revert back is quite long and painful. But we had got there by the end of the season."

As cars from two completely different sets of regulations, the technical reasons behind the limitations of the 2020 RB16 and those of 2024's RB20 were quite different. But as the team attempted to develop its way around those limitations, so it encountered a similar problem - and again the recognition of what was happening was slowed by Verstappen's extraordinary ability.

As Red Bull added downforce to the car with development, so its balance became ever-more challenging. For a time Verstappen could still make it work but eventually it got to a point where even his skills couldn't compensate. But long before this point had been reached, the car had become way too demanding a drive for Sergio Perez.

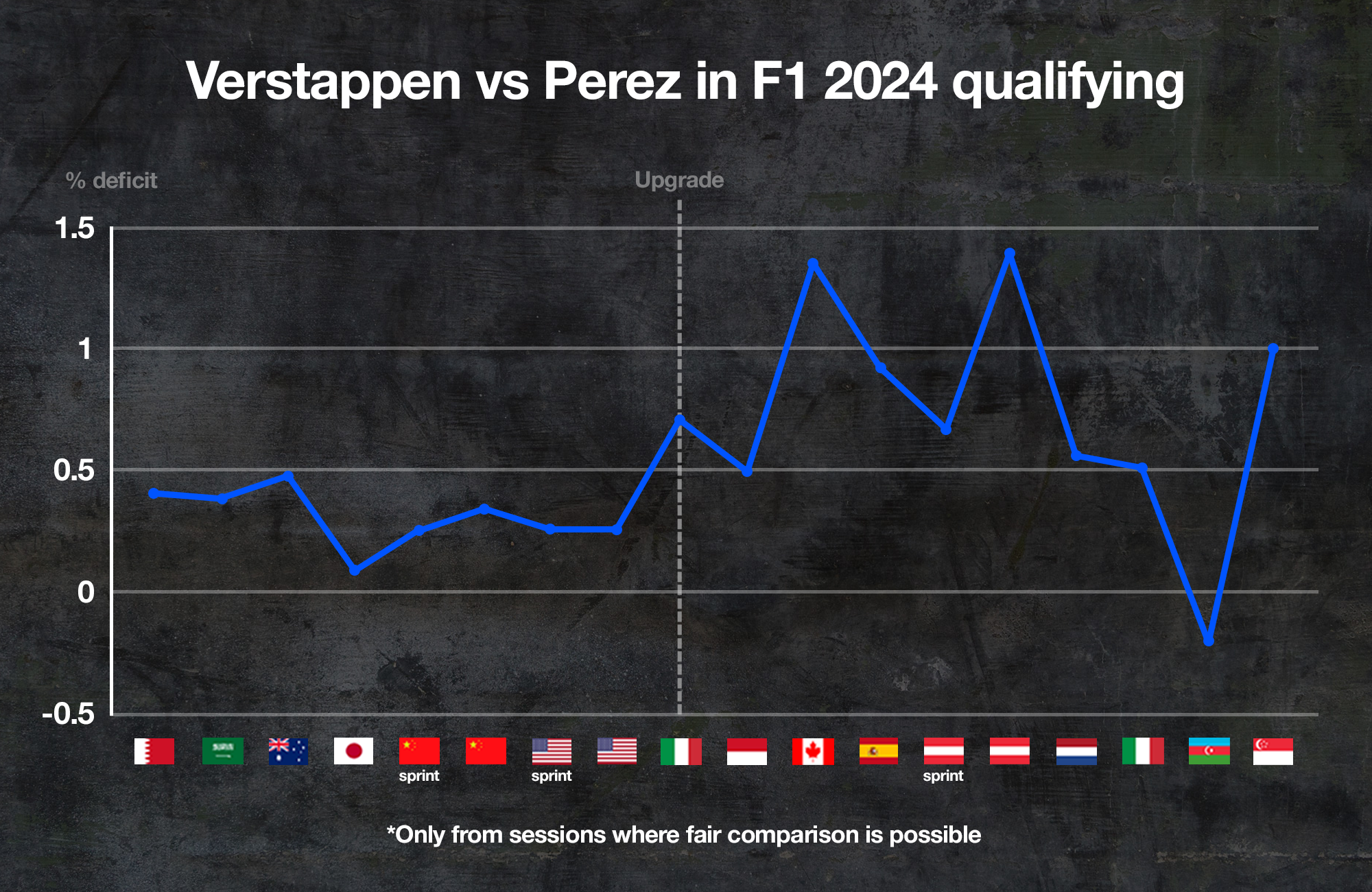

The gap between him and Verstappen really began to open up from around Imola, round seven, when a new floor edge wing which increased local load (ie towards the front) gave the car a more forward aero balance. That's when Perez's deficit to Verstappen went from small to unacceptably big - and it followed a very similar pattern to Checo's 2022 and 2023 seasons.

Verstappen's ability to exploit a very forwards aero balance on corner entry - with all the feelings of rear instability that brings - is what kills his team-mates' competitiveness. Because according to a windtunnel, the fastest theoretical F1 car has a very forward centre of aero pressure (the downforce equivalent of weight distribution). That is the most efficient way of creating downforce, with the least cost in drag.

But the windtunnel doesn't care about driveability and that feeling of instability which can make the driver sense that the car's about to throw him off the road. So there is always a softening of the transition - from straight-ahead to turn-in - incorporated into the aero maps to allow the driver the confidence to push.

"What Max is brilliant at is getting the best from a car which the windtunnel says is the best," says Jenson Button.

"Most drivers find that balance horrible and adjust the car away from that to give them the confidence to commit to corners. But Max can just drive it like that."

As Albon said: "He has the car so much on the nose, it is so sharp, that it's like a cursor on a computer screen with the sensitivity turned up to the maximum.

"When I got into the Red Bull there was so much nose on the thing that if you blew on the wheel it would have turned!

"It's like he can just turn his brain off.

"With the car like that it makes you a bit tense.

"You start off being a little bit behind, but not by much but as the season goes on, Max wants the front to be sharper and sharper and he goes quicker and quicker - and you have to take a bit more risk, and you crash.

"Then you start again, but if you're not in that flow state, and you have to think about it, it doesn't really work."

But it's not as simple as just putting more front on the car as you develop it and watching Max get faster. At a certain point, all he's doing is making it go as fast as before but calling on more of his skill to do it.

Then beyond that point, even his acrobatics are not compensating and he's going slower than he would in a more balanced car.

It isn't so much that he runs out of talent; it's more about how the aero balance no longer cooperates through all the phases of the corner - because as you engineer-in more front end on turn-in as you are braking (by inducing a bigger forward movement of the centre of pressure), so you are also inducing a bigger rearwards movement of the balance as you come off the brakes and the car levels out. Which gets you to the place which Max hates: mid-corner understeer.

It's all about how much the centre of pressure moves and how fast it moves. In 2024, the RB20's fundamental problem was finally revealed to the team at Monza, where the cars are in such low-downforce trim that their rear ride heights at low speed are as big as they ever get.

It was Verstappen who noticed in a data trace showing aero load and aero balance at various speeds that the rearwards shift of aero balance as he reduced the braking after turning in was way more pronounced than had been the case with the 2023 car. This was at the root of the mid-corner understeer that was so debilitating for him.

From there, the team understood what was happening, dumped its planned upgrades and created a new one, which debuted in full at Austin - to positive effect.

"It wasn't our intention to develop a car specifically for Max," said Wache of the RB20, "but as a driver he can cope with less connected balance. To make a quick car, by definition you go towards this.

"You still have the possibility to create an understeery car but it would be slower. Our job is to move away from this and then use the set-up to make it quicker. Max is able to cope with this and I think Alex explained very well with his computer mouse comments.

"A few years ago in Budapest in practice, Max's DRS didn't close as he hit the brakes. But he didn't fly off the road when he turned in - he just said it felt light on the rear…"

What was finally realised at Monza was that it had got to the point where Max was losing more laptime with the mid-corner understeer than he was gaining with the sharp initial rotation. But that was already way further along that continuum than Perez could handle. As recalled, they'd reached that point somewhere around Imola time in May.

Perez was the canary in the coalmine. One of the first to be adversely affected by a car with a feeling of rear instability, his drop-off in form was in hindsight the car telling Red Bull that it was now at the point of diminishing laptime returns in following that development route. Verstappen was simply disguising that with his talent.

There will be a peak in that balance range where the car is as fast as it could possibly be, for Max. That point will be further towards instability than it would be for most drivers, but go beyond it and even Max would be slower. For the reasons outlined above.

But under these regulations (with the ground effect floor venturi a long way back in the car and the big front wing which falls too readily in and out of ground effect) Verstappen would probably not like the balance of that optimum compromise car. He’d still be yearning for a stronger front - then getting angry about the increased mid-corner understeer. That's just the way the aero seems to work on these cars.

But it's a tricky point for a team running Verstappen to identify. Because there is laptime there in following that path. But only up to a point. Meantime, the team-mate can be left floundering.

So far in his short F1 career, Lawson has shown great confidence and an aptitude for adapting very quickly. For a Verstappen team-mate it's a good starting point.

How unstable a car he can live with in the way he feels it - something determined by receptors and neurons more than anything else - will likely then determine his fate.