Williams might look well placed to make a leap from the back to the front of Formula 1's midfield in 2025, but team principal James Vowles has long been clear that the team's resources are focussed on the opportunity presented by the new regulations to make an even greater leap forward in 2026.

He can take inspiration from its dramatic upturn in form when F1's hybrid era began in 2014, as well as a warning from the slump that followed.

Heading into 2014, Williams was a sleeping giant a decade on from its last year as a regular winner, with just that one miraculous Pastor Maldonado victory in Spain 2012 added to its tally in that time.

It battled adversity after parting company with BMW at the end of 2005, which also cost it title sponsor HP, potentially an avoidable fate. What followed was described as a period of "financial retrenchment". This included an IPO on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange in 2011, with Williams ostensibly back on solid economic ground.

It was an itinerant period for the team in terms of engine suppliers, with five changes between 2005 and 2014. That culminated in the crucial switch to Mercedes power units on a seven-year contract starting in 2014.

But the introduction of the 1.6-litre V6 turbo hybrid rules was preceded by a troubled time as Frank Williams and Patrick Head's succession plans stumbled. On the business side, former Goldman Sachs man Chris Chapple then Adam Parr had stints as CEO, the latter leaving when Bernie Ecclestone forced his removal, while technical director Sam Michael left in 2011.

However, 2014 was a fresh start with the market-leading Mercedes engine package, a highly visible (but bargain basement) title sponsorship deal with Martini and the arrival of Felipe Massa to join Valtteri Bottas.

To add to that, Pat Symonds had started work as chief technical officer the year before, with Rob Smedley joining from Ferrari as Williams leapt up the order.

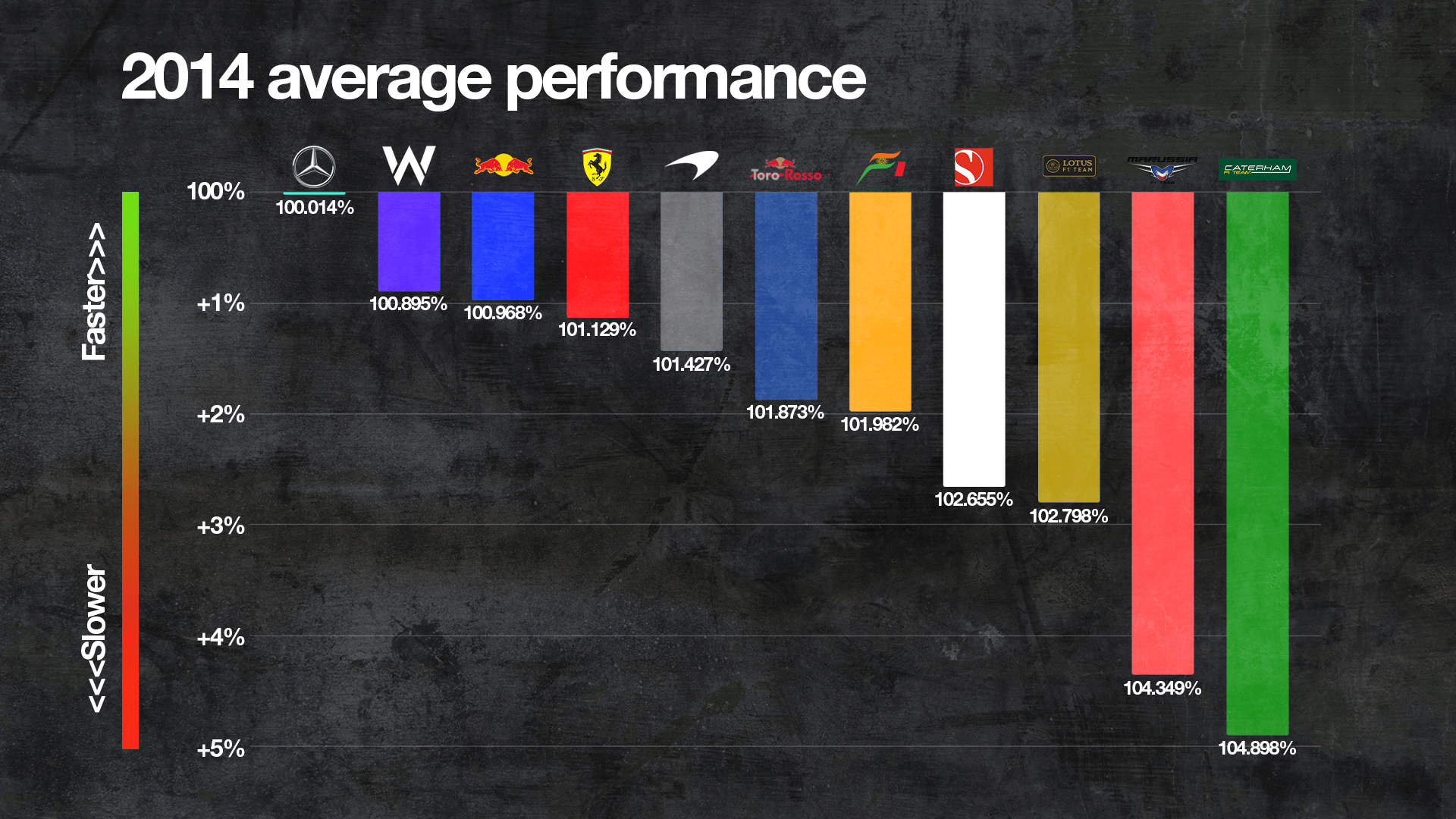

Ninth in the championship in 2013 with a feeble five points, Williams vaulted to third the following year with 320, and had on average the second-fastest car despite failing to win a race.

Wins eluding it was largely down to not being in the right place at the right time, with Red Bull's Daniel Ricciardo the driver to benefit on the three times Mercedes dropped the ball.

Canada, in particular, where Lewis Hamilton retired and Nico Rosberg limped home having lost his MGU-K, was a particular disappointment for Williams given Massa's race was compromised by a wheelgun failure causing a slow pitstop and Bottas hitting myriad problems.

But on seven occasions a Williams was the best-placed car behind the Mercedes and there were nine podium finishes - plus a front-row lockout led by Massa in Austria.

The power unit played its part, but Williams was still comfortably the best of the three Mercedes customers - well ahead of Force India and McLaren. That underlines that it was a handy car aerodynamically, and it developed well through the season.

The Williams FW36 couldn't match the downforce levels of the Mercedes, or even Red Bull and its problematic Renault engine, but it was a seriously fast car on the straights and decent through the corners. In the fast stuff, it was strong, although in slower turns it struggled a little.

It was a big step forward from 2013, with the rule changes helping - not least because that eliminated the need for Coanda effect exhausts that Williams struggled badly with the year before.

Get exclusive analysis videos and podcasts in The Race Members' Club on Patreon - join now for 90% off your first month.

Ostensibly, all was good, but the rot was eating away at Williams. Not only had it slipped behind in terms of facilities, but money was tight and investment limited. Although Williams again finished third in 2015, it was significantly weaker that season.

It fell to fifth in 2016, with Symonds departing at the end of the campaign. That was primarily because of frustration at the lack of spending on improving facilities and development, which he had expected to result from the success in 2014 and 2015.

This wasn't thanks to the team's ownership being parsimonious. Under the leadership of Mike O'Driscoll, who took over the CEO role in June 2013 having previously been non-executive director, and Claire Williams, who was deputy team principal and de facto boss, Williams was battling to survive in a tricky financial landscape.

Having stabilised itself financially, the various commercial agreements covering 2013-20 (there was no Concorde Agreement in this period, merely a range of deals that served a similar purpose) were brutal for a team like Williams even though it negotiated its own $10million annual 'historic bonus'. As Claire Williams told The Race in 2020, these combined with the complex 2014 regulations put significant financial pressure on the team.

"I wasn't involved in these discussions and negotiations, but I'm sure at the time people didn't realise how much of an impact those decisions would have - certainly on independent teams like ours," said Williams. "The financial structures clearly did not help our cause and have created this two-tier championship.

"What's happened in discussions at technical working group level, strategy group level on the dilution of the listed parts list and changes to the technical regulations haven't helped. The overly complex series of technical regulations have also crippled or crucified us.

"It sounds quite strong, but we have been trying to swim against the tide."

An owner with bottomless pockets was necessary to survive, let alone grow, but Williams was frantically treading water. It had already fallen behind the leading teams, and in the years between 2014 and the sale to Dorilton Capital in 2020 it gradually slipped further adrift.

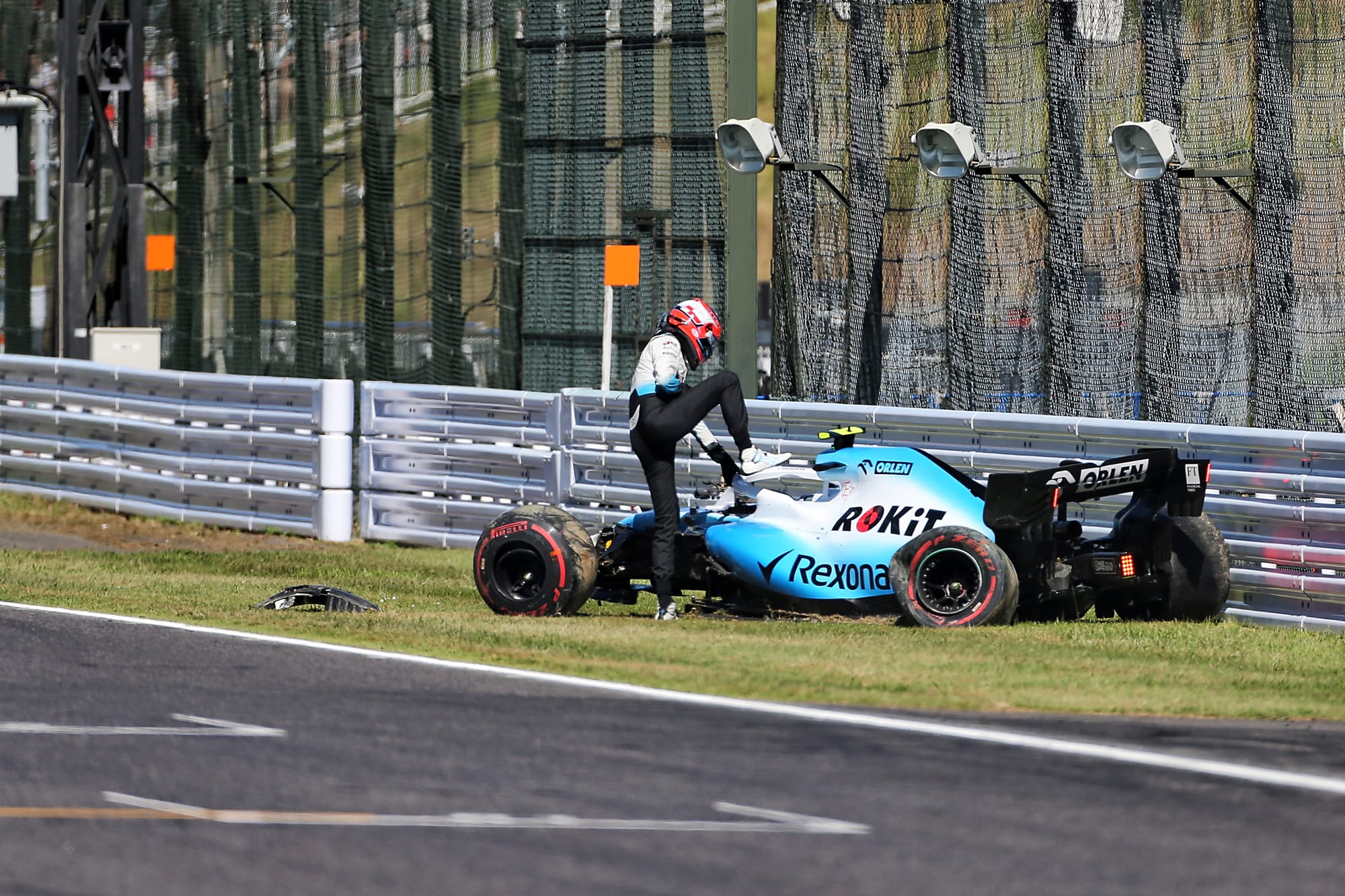

At its nadir at the end of the decade, it suffered from further missteps that meant it failed even to live up to its reduced potential, but fundamentally Williams was on a hiding to nothing. COVID-19 striking meant it ran out of credit and the team had to be sold.

The new owners are chipping away at these problems, most famously replacing its Excel spreadsheet-based monitoring of design and build projects with a more up-to-date, but costly, resource management system.

Williams's leap forward in 2014 was no more than a dead cat bounce, with little chance of it leading to a sustained return to frontrunning form. That's the big difference in what it hopes to achieve in 2026 as, with the financial conditions prevalent in F1 now very different, there should be no reason why it can't hold onto any big gains made.

The one problem is that 2026 probably comes too early to expect Williams to repeat its 2014 trick and be able to jump forward to the extent that it's the second-fastest car.