Up Next

As Andretti Global awaits what seems likely to be rejection by Formula 1 and its existing teams, the Andretti family probably feel like the F1 paddock is against them.

And that's a familiar feeling for them.

Michael Andretti has said that the 13 races he did in F1 with McLaren in 1993 nearly ruined his career. And you can see why.

While Ayrton Senna was taking the fight to Williams and Alain Prost from the other side of the garage, Andretti had an average starting position of 9.77 by the end of the year, spun or crashed out of six races, and only scored points three times.

By mid-season, he was fighting race by race to keep his seat, with McLaren keen to give reserve driver Mika Hakkinen a shot alongside Senna instead.

Despite ending on a high with a podium at Monza in what he already knew would be his final start, his stint was a nightmare. And both Michael and his legendary father Mario - the F1 world champion in 1978 who was desperate to see his son succeed there too - believe it might not have been coincidence that Michael’s attempt to crack F1 went so badly.

Could there really have been a conspiracy behind all this? Or was it just bad luck, bad timing, and simply Andretti doing a bad job in the second-best car on the grid?

THE ODDS AGAINST ANDRETTI

Andretti had been on McLaren’s radar for some time, signing a testing deal with it as far back as 1991, the year he would go on to win his only IndyCar title in America.

But by the time he landed his F1 race seat for 1993, it couldn’t have been a worse time to make the switch.

Pre-season, McLaren team boss Ron Dennis had been bullish about the adaptation Andretti would need to make.

"Michael has tremendous commitment and aggression," he declared. "I’d rather have a full-blooded racing driver who has got to learn F1 than an F1 driver who’s got to learn to race."

But 1993 was the peak for high-tech gizmo F1 cars, before driver aids were banned for 1994. While F1 cars were always more refined than their Indy counterparts, the gap was never bigger than it was that year.

Despite all the tech he had to adapt to in F1, Andretti actually liked that side of things. He enjoyed being able to programme the car to “do whatever you wanted”. What bothered him later was that he felt his car didn’t always do what it was supposed to.

There’s no question the odds were stacked against Andretti.

He joined just as McLaren lost its works Honda engines and had to settle for customer Ford V8s after a bid to land the same Renault engines as Williams failed, and that Ford deal came together so late he only got a day and a half of testing in the 1993 car before the season started.

Plus F1 - in an attempt to cut costs - limited drivers' practice laps to 23 per session for 1993. This was a disaster for a driver trying to learn a new type of car and tracks he’d never seen before.

HOW HIS SEASON WENT OFF COURSE

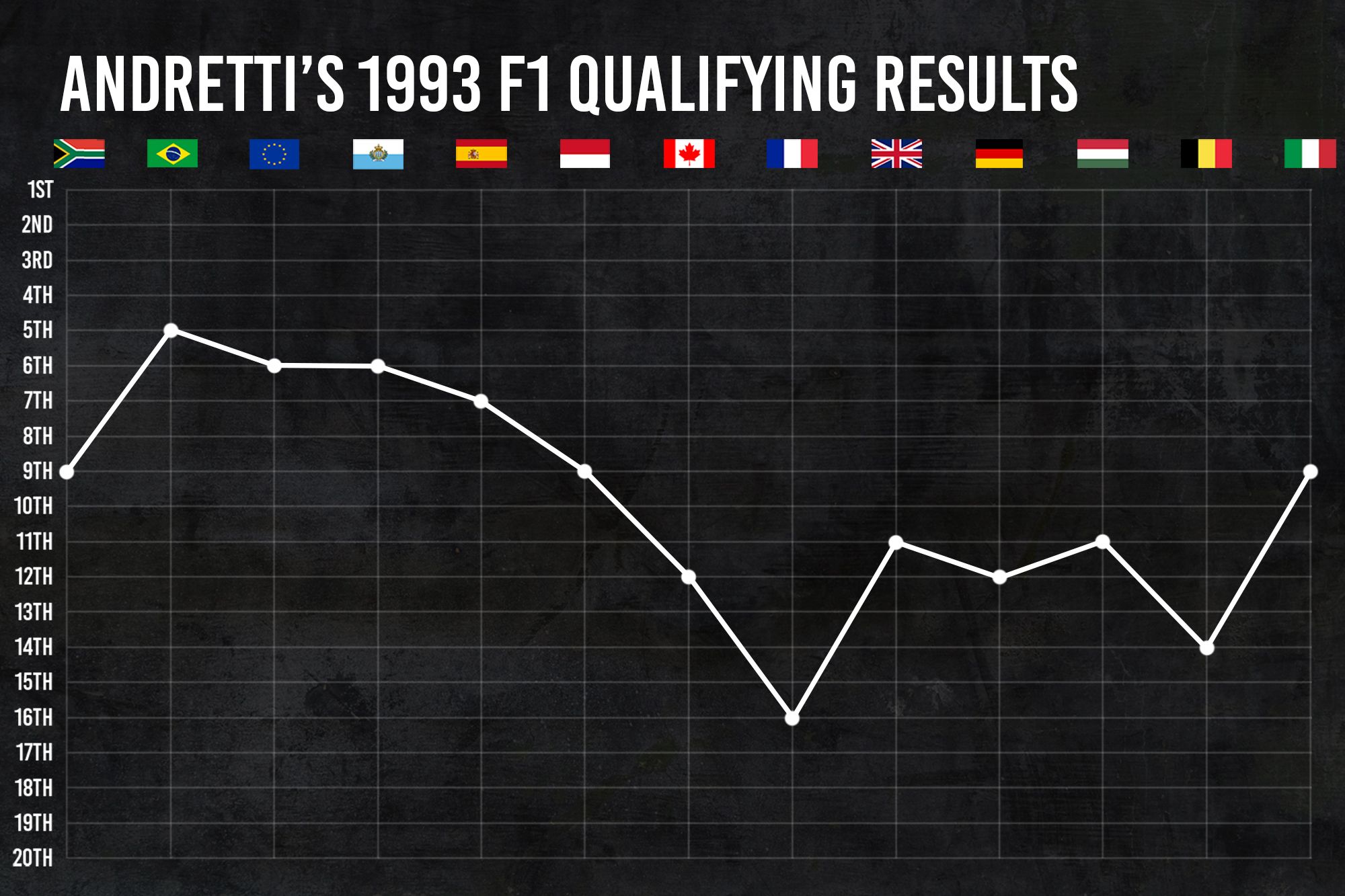

Despite this, he qualified in the top six for three of his first four races, and was in the top nine on the grid for all of his first six grands prix.

The problem was things kept going wrong on Sundays. Andretti was either let down by his car, or crashing or spinning out of races far too often.

Andretti’s qualifying performances took a dive mid-season. Having qualified in the top 10 on those first six appearances, in his next six he wasn’t in the top 10 once.

Dennis tried to put things right in Canada in June with a pep talk, where he told Andretti: “From now on, race the way that you want to race, and we’ll just live with the consequences. If you fall off, you fall off.”

But it didn’t work. There were more errors, and more car problems.

THE HAKKINEN FACTOR

Andretti arrived at McLaren at a time of internal turmoil. As well as losing Honda, for much of the off-season between 1992 and 1993 it looked like McLaren would lose Senna too.

This led to Andretti and Hakkinen being named as the team’s driver line-up, but Hakkinen moved aside when Senna signed at the last minute - initially on a race by race deal for $1million per race.

The problem was, Hakkinen was promised he would get a chance to race later in the year. McLaren even submitted paperwork to the FIA to confirm that if any teams dropped off the grid and numbers fell below 26 cars, it would run a third car for Hakkinen.

That scenario never materialised, so when Senna committed to the rest of the season prior to the French Grand Prix at the start of July, Andretti was doomed.

Andretti says that from that weekend onwards, Dennis told Michael he wanted him out of the car so Hakkinen could drive, and the Andrettis had to fight race to race to keep the seat.

The other thing that Mario believes always worked against Andretti was that Senna’s last-minute U-turn left McLaren with two expensive drivers, while a young, fast and cheap test driver was sat on the sidelines.

THE HINTS MCLAREN WANTED ANDRETTI OUT

McLaren tried to be supportive early in the season. But by the middle of the year the tone changed. After the first six races, the team felt Andretti had lost his way and was being too conservative.

In the summer Dennis fuelled speculation around Andretti’s future with a bizarre statement, where he said: “We pride ourselves on fulfilling our legal and moral commitments to drivers. If any driver did not complete a season in a McLaren car for which he was contracted, it would only happen by mutual agreement."

The frenzy that comment caused forced Dennis to clarify it, but his clarification only made things worse.

“I don’t think Michael’s enjoying Formula 1, and it’s probably hurting his career," was Dennis's argument.

“If he chose to talk to me about going back [to IndyCar], I wouldn’t wave a contract at him.”

He claimed this didn’t mean he wanted to replace Andretti, but it looked like a pretty clear hint for Michael to see what opportunities might be waiting for him back in America.

SABOTAGE?

The timing of Senna committing for the rest of 1993 just ahead of the French Grand Prix looks significant because that’s the weekend when the biggest accusation that’s been made by the Andrettis supposedly took place.

The Andrettis say the “beacon” on Michael’s McLaren was shut off during qualifying in France, meaning the car didn’t know where it was on the track, so the driver aids such as active suspension couldn’t behave in the way they were supposed to from corner to corner. As Michael Andretti described it to veteran US journalist Gordon Kirby: "My car was just lost.”

"Throughout qualifying it was raising the car and lowering the car and changing gears and not changing gears," he continued. "It was a mess."

That led to Andretti’s worst qualifying performance of the year, down in 16th place, 1.4s slower than Senna.

It actually preceded one of his stronger races, as he came through the field to sixth.

"I started passing like I would in an IndyCar," Andretti told Sports Illustrated at the time.

"There isn't a single car in that field that will give you a position - ever - and I was running into some heavy blocking. But I stood my ground when they tried to put me in the grass. I kept my foot in it.

“You have to be a little more arrogant the way you do things here. If you're a nice guy, they eat you alive. They lose respect for you. You can't wait for things to come to you, because they don't."

Active suspension systems were capable of going wrong on their own, but Andretti believes what happened in Magny-Cours qualifying was done intentionally by someone who wanted him out of the team.

A BERNIE PLOT?

And he’s said in the past he thinks that stemmed from a motivation led by former F1 ringmaster Bernie Ecclestone - who was 'using' Andretti to make a point.

Michael told Kirby that he felt he was “destined to fail from day one” in F1, because Ecclestone wanted to discredit IndyCar racing.

“Bernie was worried about our series. I think I was used as a tool," he continued.

“They wanted to discredit me because I was one of the big guys in IndyCar.”

If that sounds far-fetched, there are a few factors to consider: IndyCar had been on the rise for a few years by this point, and Ecclestone had been taking shots even before F1 lost its 1992 world champion Nigel Mansell to the series. Ecclestone kept challenging IndyCar to a head to head race with F1 cars, and claiming that no IndyCar drivers would even qualify if they entered an F1 race.

“Formula 1 is like heavyweight boxing, and IndyCar racing is like wrestling," said Ecclestone in 1993.

“It’s a form of entertainment, but I don’t think the drivers get satisfaction out of it.”

Ecclestone then bought Mansell out of his IndyCar contract to get him back onto the F1 grid for 1995, and a year later he helped engineer Jacques Villeneuve’s move to Williams, costing IndyCar one of its most famous names and the reigning Indianapolis 500 and series champion.

So the idea that Ecclestone would want to hurt IndyCar racing makes sense.

The bit that doesn’t quite add up is why McLaren would agree to hobble one of its own drivers. Yes, as Mario Andretti said, it had a cheap alternative in Hakkinen waiting in the wings, but any race team would surely have preferred to see two of its cars up the front every weekend if that was possible.

Michael has a counter to that - he told Kirby that Dennis and Ecclestone “were in it together” because "they wanted to say we couldn’t make it in Formula 1", and that the racing results were “secondary” to making millions of dollars.

Years later on the Marshall Pruett podcast he was a bit less direct, but still hinted at feeling “used”, saying: “I understand why things happened, why people did what they did. It was never a personal thing. It was, because of where I was in my career over here [in IndyCar], sort of just used in a different way.”

McLaren had told Andretti during 1991 - before he won the IndyCar title - that it wanted him for 1993. If that was part of a dastardly plan with Ecclestone to discredit IndyCar racing, then everyone involved was certainly prepared to play the long game.

THE MORE LIKELY EXPLANATION

Might McLaren have just lost interest in Andretti as the year went on and he kept making clumsy errors? With Hakkinen waiting in the wings, it’s surely plausible. Would McLaren go into business with Ecclestone to sacrifice one of its own cars to hurt IndyCar racing - a series it had recently considered joining itself at that point?

Did Andretti just need more time? His father reckons he should have made sure he stayed at McLaren for Senna's end of 1993 exit and even predicts that if that had happened, it would've eventually been Michael, not Hakkinen, ending McLaren's title drought in 1998.

"Michael was brutally quick. He got screwed over with McLaren," argued Mario on F1's Beyond the Grid podcast.

"If he would have listened to me and just toughed it out, he would have been world champion. He was quicker than Mika Hakkinen.

"Michael needed to sit down with Ron, and say, 'I want to stay, I want to win a world championship with you'.

"But he let his manager, who was a nice guy, talk for him.

"That was Michael’s fault. He got screwed the first year but he could have toughed it out."

At the time, though, Michael repeatedly cited mileage and confidence as being what he lacked.

"In an IndyCar, you can go into a corner, and it’ll tell you if the front’s not going to stick, or whatever," he said on the weekend of his F1 debut.

"In an F1 car, though, it seems like you can’t find that out unless you commit yourself, and that’s been one of my problems, because I don’t have the confidence yet. The only way I’ll get it is with miles.

“I’m finding I have to reprogramme the way I drive. An IndyCar you can really throw around, especially in the slow corners, and it pays you back on time. But when I do that in the McLaren, I go slower, so that’s a challenge I’m having to learn.”

Nearly four months later, speaking after the French GP, it sounded like little had changed for having eight races under his belt.

"The car has to be an extension of your body, and I'm still searching for that," he told Sports Illustrated. "It's not fear. It has nothing to do with fear.

"You have to have enormous confidence in these cars. When you get into a corner, you have a tonne of grip. But then there's a point at which you can lose the grip just like that.

"You have to commit yourself to staying on the throttle. I have not proved to myself that the car will stick. Once I do it, I'll know."

He never got there. And despite the conviction with which the Andrettis speak on the conspiracy subject, it still feels far more likely that this was down to the turbulent circumstances of McLaren's season clashing with the scale of transition Andretti needed to make.