Up Next

Williams has made a compromised start to the 2024 Formula 1 season as the result of a painful winter that has laid bare just how far behind the team had fallen in key areas.

One of F1’s most successful teams is, it hopes, out of a long-standing malaise and is now in the heart of a revolution. One that has brought a lot of pain – some expected, some less so.

It’s no secret that Williams has been battling with under-invested facilities and an outdated culture for many years, with claims of the team being 20 years behind its rivals.

But the extent of that, or rather how desperate its situation looked ahead of the 2024, can only really be grasped now team principal James Vowles and chief technical officer Pat Fry have opened up about the depths of a difficult winter and the real impact it has had on its point-less start to the new season, costing Williams laptime and valuable cost cap resources.

Cast your minds back a few weeks and the only car you hadn’t seen until the day before pre-season testing was the Williams FW46. It was late, and Williams had been quite open about that – and the fact it was taking “huge amounts of risk”.

But this was not, it turns out, just a matter of Williams trying to massively overhaul a car design philosophy that had some specific performance weaknesses. It was much more fundamental with a greater impact than could have reasonably been imagined.

A CAR BUILT IN EXCEL?!

Vowles has been banging the same drum about the team’s outdated working practices and systems since he joined early last year, and a key decision he made was for Williams to consciously make life harder for itself with its 2024 car.

He and Fry believe it is impossible for Williams to compete for anything significant in F1 without making a massive step forward in how it operates as a team.

The main winter example was Williams dramatically changing what Vowles calls the car’s technology base – basically how it designed and built the chassis: “Our chassis went from a few hundred bits to a few thousand bits. That's just one part of the car.”

Alongside this Vowles wanted the development team to work more in tandem, pursuing a different approach between aerodynamic and mechanical items so that the philosophy of designing the car changed as well.

He also banned the contingencies he discovered existed in building the 2023 car – like using year-old parts that were modified to fit the new car, or metal parts instead of carbon, which it turns out was initially the case on last year’s FW45.

The upshot of all that was what Vowles describes “tenfold increase in some areas with the amount of bits going through”, using the same limited infrastructure he has complained about for so long and that Williams is in the process of slowly investing in and improving.

Vowles reckons that if Williams had stuck with its usual processes and committed to a simple evolution of the 2023 car, things would have been fine.

But the impact of the big change he wanted to commit to was compounded by terrible systems that he had already seen have a negative impact on the team’s only real in-season upgrade of 2023 – resulting in what he calls an “extraordinary” cost, one “higher than I anticipated.

It is not an exaggeration to say that up to and including at least the initial work on the 2024 Williams, its car builds were handled using Microsoft Excel, with a list of around 20,000 individual components and parts.

Unsurprisingly, ex-Mercedes man Vowles - someone used to class-leading operations and systems – had a damning verdict for that: “The Excel list was a joke. Impossible to navigate and impossible to update.”

Managing a car build is not just about listing all the components needed. There wasn't data on the cost of components, how long they took to build, how many were in the system to be built.

“Take a front wing,” says Vowles. “A front wing is about 400 different bits. And when you say I would like one front wing, what you need to kick off is the metallic bits and the carbon bits that make up that single front wing.

“You need to go into the system, and they need to be ordered. Is a front wing more important than a front wishbone in that circumstance? When do they go through, when is the inspection?

“When you start tracking now hundreds of 1000s of components through your organisation moving around, an Excel spreadsheet is useless.

“You need to know where each one of those independent components are, how long it will take before it's complete, how long it will take before it goes to inspection. If there's been any problems with inspections, whether it has to go back again.

“And once you start putting that level of complexity in which is where modern Formula 1 is, the Excel spreadsheet falls over, and humans fall over. And that's exactly where we are.

“There is more structure and system in our processes now. But they are nowhere near good enough. Nowhere near.”

Missing that raw level of data makes it easier to understand how 20,000 bits end up in limbo. In the scenario Vowles describes, an Excel spreadsheet is “useless”, with emails bouncing back and forth between people and departments chasing missing information. Vowles recalls hearing shop floor workers at Williams saying ‘I don't know where this component is’ and having to physically look around the factory for certain parts.

Suddenly this same team having such a bad 2019 car build that it managed to miss the start of pre-season testing makes more sense. Vowles didn’t seem to fear the same fate this time but admits he had little confidence that the team would have everything it needed by the first race of the season.

He is amazed at how Williams rallied and managed to produce what he reckons is more than any other team in a shorter period. But he also admits they did it to themselves.

‘NEVER KNOWN ANYTHING LIKE IT’

This has been - to a greater or lesser extent - the reality at Williams for many years.

It almost makes it a wonder it has managed to achieve what it has in recent years battling such organisational chaos. And how the winter of 2019 was not a more regular occurrence.

Vowles and Fry were new to this, hence their shock at living this reality for the first time - and recognising it needed to change.

According to Vowles, the Excel spreadsheet was being migrated to a digital system at the same time the car’s “technology base” was going through its own colossal overhaul.

Unsurprisingly, doing both in tandem was a nightmare. Williams was completely changing how things were stored digitally within the organisation and the quantity of parts being produced to be logged in this new system people were unfamiliar with.

Delays led to workers having to sleep at the factory and effectively pull overnighters to get things ready. Vowles recalls the car was still just a big bag of bits by January, while Fry says: “If you go back to how we worked, whatever, 20 years ago, loads of bits would be late and someone will put their Superman underpants on over the outside of their trousers, rush round and save the day.

“We're still kind of working in that mode, really.

“Performance comes from sensible planning and optimising the bits that…I'm never gonna give anyone an easy time, but it needs to be the performant bits that we leave last, because we're finding more lap time in the windtunnel. Or if there's a suspension development that we push late.

“We just need to be a little bit smarter about the way we go about things.”

Fry reckons Williams’s process of making a car is inefficient, leaving everything “massively late” without a good performance-based reason for that being the case. Williams signed off the relevant aero surfaces quite early in the process yet was still somehow scrambling around for parts late on.

That’s because the flawed processes caused a mountain of parts to pile up, delaying production. It wasted time, and wasn’t cost efficient either, which is relevant in F1’s budget cap era. Fry says what Williams managed to do this winter was “viciously expensive”

“I've never seen anything like it,” Fry says. “Don't want to live it again. I'm sure James doesn’t want to live it again, either.”

Vowles doesn’t. He wasn’t sure how Williams would make up for the limitations.

“Unfortunately, it's through humans pushing themselves to the absolute limits and breaking,” Vowles says.

“That’s how we make up for it. And that's why we can never go through this ever again.”

HOW IT HURT FW46

As it happens, the early 2024 results do not necessarily reflect a team coming off a desperate winter. It looks like the team’s been remarkably stable given its results are near-identical.

Williams is one point worse off after two races than a year ago but it’s still seventh in the championship – and first of the non-scorers! – by virtue of Alex Albon’s 11th place in Saudi Arabia.

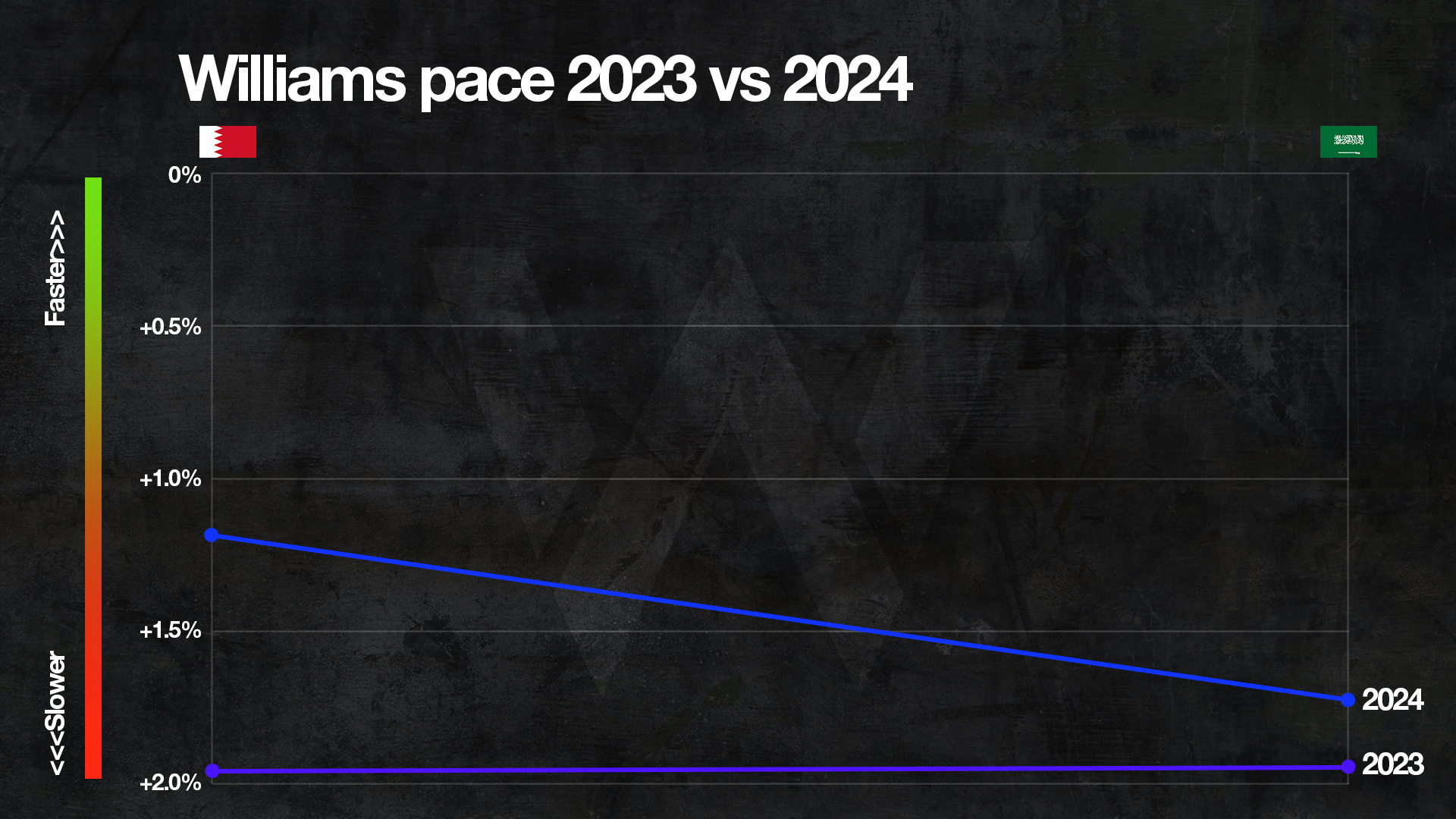

In fact, Albon finishing 15th and 11th in Bahrain and Saudi means Williams is very close to the 10th and 16th it scored in the same races a year ago. It has also cut its deficit to the front – from just under 2% adrift of the fastest car at both circuits last year to 1.2 and 1.7% off in 2024.

Albon sees something bittersweet in that. It’s encouraging for Williams but it wanted more. The car is better, certainly, and what it has aimed to improve with its new approach to development has paid off, so the foundations look decent. But still compromised.

“We hurt ourselves,” says Vowles.

“Do I think we had reliability issues at the beginning to test because we were underprepared because we were right up into the limit? Absolutely.

“But has it brought performance? Yes. Could we have more performance if we're more structured, organised, and everything was delivered earlier? Absolutely.

“There's a tremendous amount in the locker. We're not short of ideas and how to make the car faster. I'm short now of cost cap finances to make the car faster, and time.”

This appears to have been a very necessary pain to experience. Vowles believes Williams is already better off for it in some areas, while Fry says that the lingering problems will definitely be addressed for the 2025 car build. That’s why Vowles says everything they’ve revealed about the winter doesn’t worry him “for a second”.

The belief is this can and will be fixed, partly through better processes, and partly because the team leaders are adamant there isn’t a problematic resistance to the cultural changes being enforced. It’s uncomfortable for some, they admit, but everything they are preaching is based around obvious ways to make the workers’ lives easier.

Vowles reckons it’s a three-year process to get a 1000-strong workforce to fully adopt a new culture. But before then he believes Williams has an opportunity “that does not exist anywhere that I know that’s competitive up and down the grid”.

“It’s an opportunity that's not small,” he says.

“It's millions of pounds of cost cap money. And it's tenths of performance in just having processes, structure and system.”

Albon, who needs Williams to prove to him this year it is ready to become a top team on a timeline that works for his own career, is optimistic that Williams just has to “take its medicine, realise it’s for the best, and hopefully enjoy some success a bit later on into the year”.

Beyond that, the expectation must be that this team will spend future winters getting things done on time and chasing performance instead of shooting itself in the foot.