Up Next

Alpine’s current struggles mean that realistically it will be 2026 and the new regulations before the team can hope to make the leap forward that has been promised - but never delivered - ever since Renault recreated its works Formula 1 team ahead of the 2016 season.

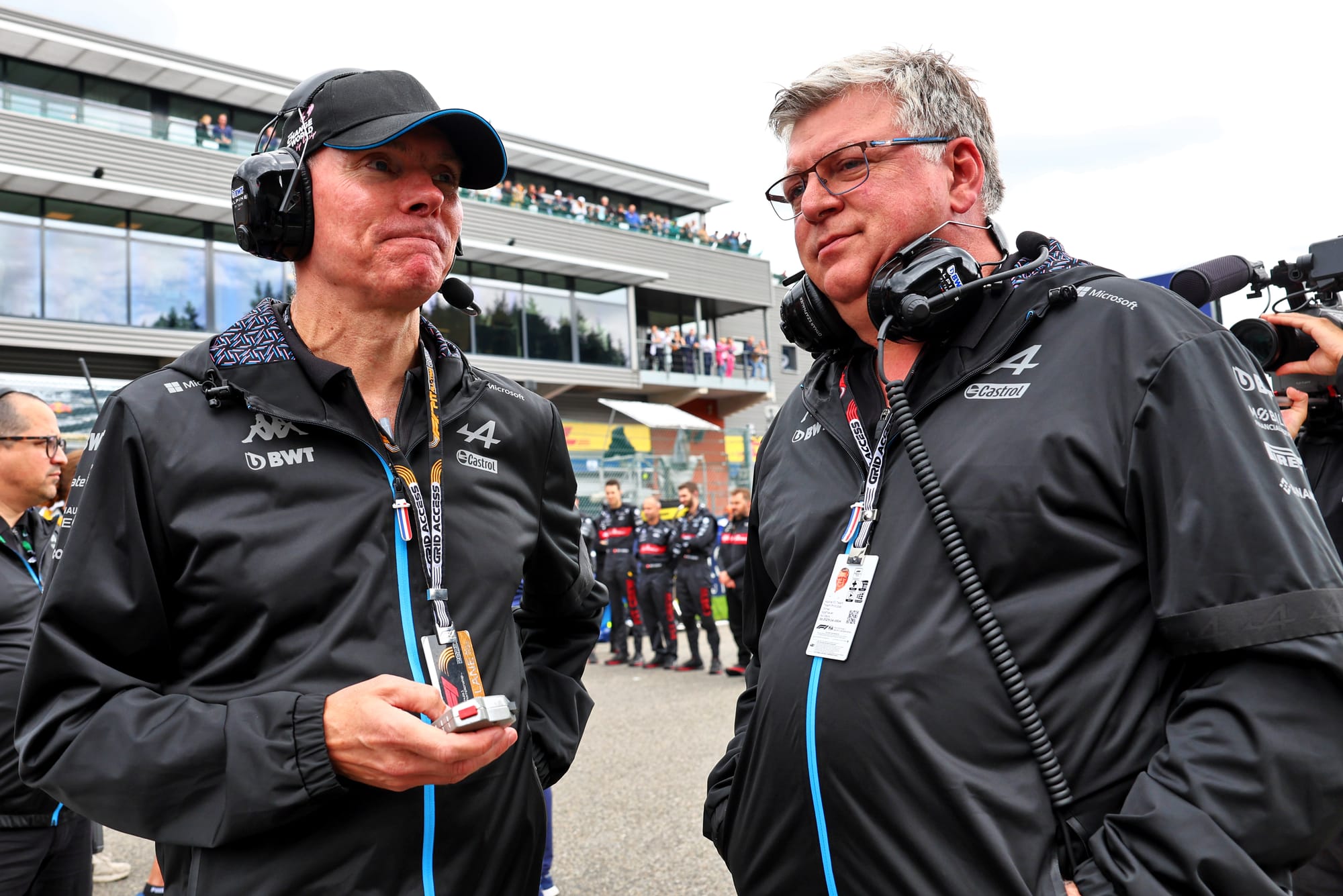

And former team boss Otmar Szafnauer, who left after last year’s Belgian Grand Prix, doubts the team’s ownership ultimately understands what it takes to be successful.

Szafnauer has been working on EventR, described as a “groundbreaking digital itineraries system” during his post-Alpine gardening leave ahead of a possible return to F1 in the future, with EventR already used by several teams in F1.

His departure from Alpine, along with that of sporting director Alan Permane, came as a shock and represented a sudden shift in direction for the team in the middle of the 2023 season.

Key to their exit was a disagreement about the timeline for success, which Szafnauer and Permane felt could not be delivered to meet the unrealistic expectations of Renault.

At the heart of that is an automotive company not listening to F1 specialists with a deep understanding of how to make such a project successful, which echoes former chief technical officer Pat Fry's criticism that Renault didn't have the ambition to do better than fourth.

Asked by The Race if Renault understands what it would take to achieve its objectives in F1, Szafnauer replied: “Not from what I saw”.

He continued: “Not just Renault but big car companies, even car companies that have racing as part of their DNA, shouldn't meddle.

“It's so much different from a car company, you should just leave it to the experts.

“The only similarities are: you have five wheels on a car and five in a racing car - four wheels and a steering wheel – and that's it. The rest is so different.

“Yeah, you call them a car, but the technology development is different, the technology you use is different, the level of the engineering that goes into it is different, the level of the education of the engineers is different.

“When I was at Ford Motor Company, they had two management paths. One, you could take a technical management path, so if you're a PhD in mechanical engineering or aerodynamics you could take a technical management path as opposed to a [non-technical] managerial path. And there weren't that many PhDs in engineering in a huge company.

"When I was at British American Racing, I think it was [team deputy technical director] Gary Savage once said ‘we've got more doctors here than a local hospital’, which is true. And they don't come from mediocre universities, they're all from Oxford, Cambridge, Imperial. Not so much America, but we've had I've worked with some from MIT, from Caltech.

"So a) they're super bright, b) they're educated to the highest level in Formula 1 and most importantly, they love the sport, which is why they're motivated like hell to win. And you don't get that in car companies.

"I'm not saying this about Renault, but I will say it about Ford where I was. We used to have a saying at Ford that Ford Motor Company didn't make cars, it made careers. So when you were there, you cared about the car programme you're on, but you care most of all for your career, whereas in Formula 1 you care about on-track performance. And that's a significant difference.”

This manifests itself not only as Renault's long-term tendency to underinvest in F1, with claims made about efficiency advantages being able to get it ahead of bigger spendings repeated over the years but also in underestimating the timeline involved and dedication required.

Having not spent enough before F1's cost cap was introduced, the time required for it to eliminate infrastructure disadvantages is extended further. Therefore, while the team has plenty of accomplished personnel, they are held back by the limitations of the ownership.

Alpine’s form has dropped off dramatically this year, the team scoring no points in the first five races. There was a slight upturn in form in China following a floor upgrade and the introduction of a new, lighter, chassis for Esteban Ocon, although that was only enough to finish 11th in the grand prix.

Those struggles are the result of a series of missteps with the car, most significantly the failure of the lateral load test for the chassis that necessitated countermeasures to strengthen it that added significant weight.

Aerodynamic targets were also missed, meaning that Alpine has started the season at the back with the best-case scenario from here recovering to sixth place in the constructors’ championship.

Szafanuer countered claims by his successor as team principal, Bruno Famin, that responsibility for the underperformance of this year’s Alpine A542 lies with the old regime. Famin recently told F1.com that “the car we have now is the result of previous management”, with Szafnauer initially replying “that is a good question” when asked for his reaction to Famin’s claim.

Szafnauer argued that the timeline for car development invalidated that claim, with the only key decision that influenced this year’s situation the logical one to have a brand new chassis given cost cap regulations means it was sensible to have largely the same chassis for two years - initially for 2022-23 - meaning the need for a new one this year.

Szafnauer argued the timing of his ousting and that of sporting director Permane just before the August break, as well as the earlier departure of chief technical officer Fry to join Williams, means they can’t be held responsible for Alpine’s current plight.

“We have limited CFD and wind[tunnel] on time and geometries, so you can't even use one windtunnel to its full - probably half capacity, as well as CFD,” said Szafnauer.

"So because of it and the way the [aerodynamic testing regulations] reporting structure goes almost everybody works on the current car up until the break.

“And then depending on how quickly you can produce the findings up until the break, some of those upgrades come as late as Singapore [in September].

“If you can produce them quicker, you get them on the car quicker, but generally Singapore is your last big upgrade.“That last big upgrade in Singapore was conceived in June/July, right before the break.

The Race was among a group of media outlets that attended a launch event for Szafanuer’s EventR, described as a “groundbreaking digital itineraries system” originally developed for the use of F1 teams to manage complex travel arrangements and communications.

Produced by SoftPauer, which Szafnauer is chairman of, it has now been rolled out to a wider audience and is aimed at businesses, smaller groups and individuals.

“After the break, everyone switches to next year's car. You might change a tub, you might change geometry, you might go from pullrod to pushrod, you change stuff. And when you change it, you mainly change it for aerodynamic benefit.

“So now you start your model changes and you're starting to do different experiments that don't necessarily apply to this year's car. It's what happened at Renault.

“Alan and I left in July and after we left, they started on next year's car. And Pat had resigned by then as well. So to the uninformed, you can say all these problems were caused by those guys, but I don't think so.”

Famin has argued that Renault is more committed than ever to its F1 team and is adamant it has the support it needs.

The true test of that will be the new car and power unit regulations in 2026, when Alpine must take a big leap forward.