Up Next

Mercedes technical director James Allison has a hope he describes as “just a little bit that nestles in the back of our heads” that would not only help his team have a more competitive season, but also be a boost for Formula 1 fans hoping for a closer season at the front.

That’s all down to what he describes as the “upper bound in laptime” that all teams, notably Red Bull, will push up against in the third season of the ground-effect regulations introduced in 2022.

This hope, admittedly stated in 2023 and before the appearance of a more aggressively-evolved 2024 Red Bull than expected, is not just founded in the fact F1 is running to the most prescriptive regulations there have ever been, but also the nature of these types of cars.

These allow prodigious downforce to be produced by being close to the ground but this is limited by the capacity to avoid the related problems of bouncing and porpoising, and the need to ensure good performance across a wide range of corner-speed profiles.

Any set of regulations will have a theoretical optimum performance level, which is why Allison refers to gains under the current rules as becoming 'asymptotic'. In simple terms, this is effectively the way that the development curve gets increasingly shallow with time as performance gains become smaller.

“The rules themselves have a much more clear upper bound to them in the amount of laptime these cars are capable of producing,” said Allison. “A much more clear upper bound to them than the older generation of cars, which the more love you gave them and the more labour you put into them, the faster they got seemingly without end.

“If you look at last year, you see from the start of the season to the end of the season, although Red Bull's dominance was near complete and they didn't look vulnerable even to the last race of the year, this is a grid that is gradually compressing.

“All the cars in Q1 were sort of squashed down within one second of each other and that's not coincidence, it's a trend that has happened from 2020, continued in 2023 and I think will continue to show itself in 2024 because the gains are getting more and more asymptotic.

“Therefore, in addition to us, I hope, having worked well [with designing and developing the new Mercedes], my guess is it's going to be relatively busier near the top of the grid this time around than last.

“And if you're good enough to be in that fight then operational things - driver excellence, the reliability of the car, the skill of the crews that service it, all of those things - start to potentially become the differentiating factors. And hopefully there too, we've given a good wash and brush-up to performances that were sometimes less than stellar last year.”

One of the stated objectives of these regulations was to make F1 closer. While you can argue that Red Bull’s unprecedented dominance of 2023 proves that’s a failure, if you look at the single-lap pace spread from front to back it is remarkably close.

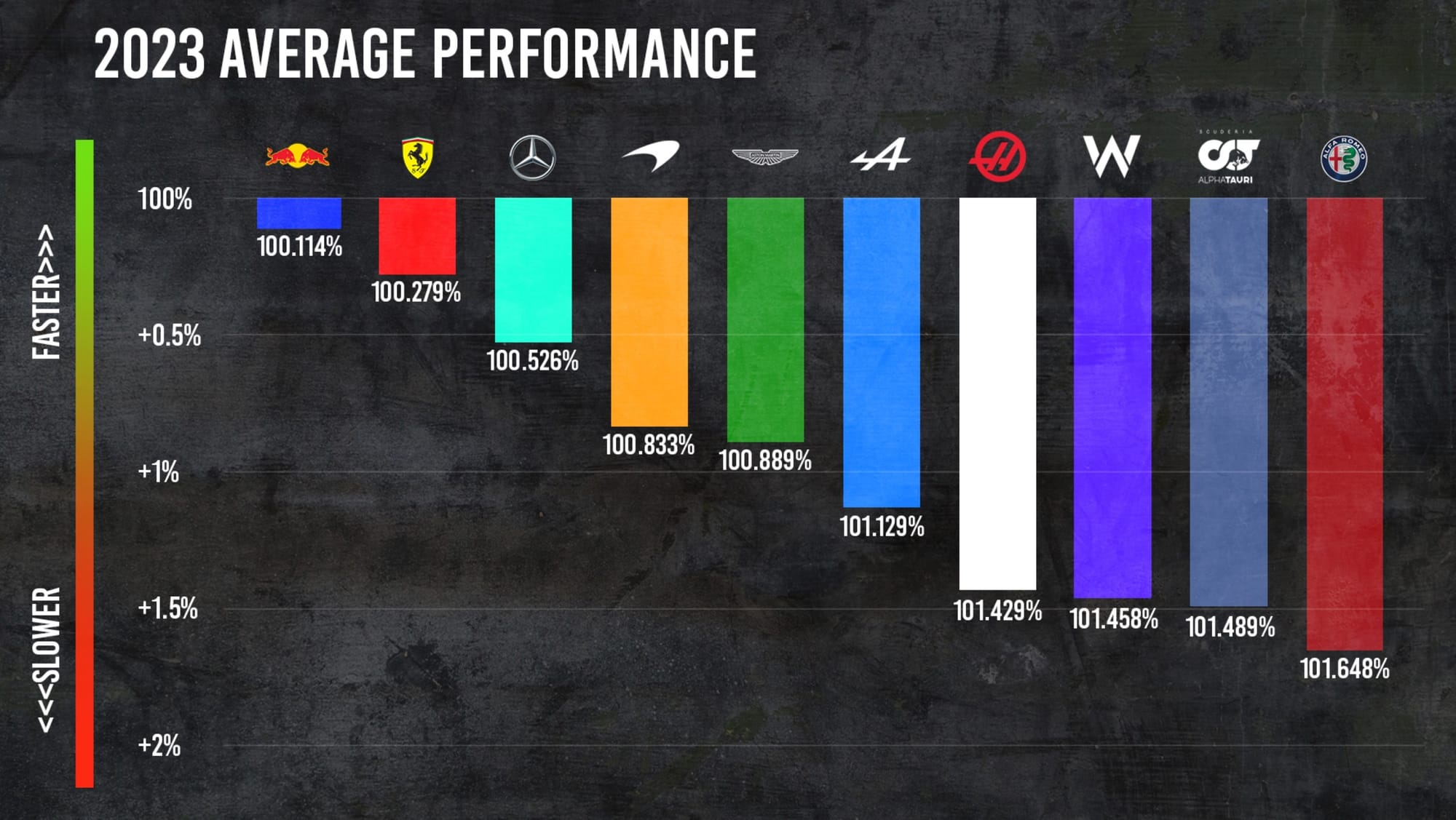

Using The Race’s ‘supertimes’ methodology, which takes each team’s fastest single lap of a weekend and measures it as a percentage of the outright fastest, the slowest team on average was 1.6% off the pace in 2023. Around a hypothetical 1m20s lap, that equates to around 1.4 seconds.

Allison references 2020, where the gap was 2.9%, rising to 3.3% in 2021 - largely thanks to Haas effectively giving up on development that season. For the start of the new regulations in 2022, the spread was 2.6%. The 1.6% figure last year is actually the second-closest in F1 history when looking at front-to-back pace, second only to 2009 when the spread was 1.4%.

The teams playing catch-up should be able to make more progress than those at the front, which means there’s every chance things will get closer this year. That’s helped by the fact that the fundamental design compromises required to extract the most from these regulations appear to have been well-understood.

This will mean - as already evidenced by launch season - most will largely be following a similar design direction to that set by Red Bull.

“Most people will be iterating down a similar sort of avenue,” said Allison when asked by The Race what potential there is for new ideas. “It doesn’t mean there isn't room for innovation at all.

“It's no secret these cars run super near the ground and that's where they get their best performance, but there's also the ground there, so just trying to figure out how you can reliably, precisely and in an informed way place the car at a point above the ground which you know will be survivable from the skids point of view, the skid legality point of view, but will give you every bit of the downforce the car is capable of offering. There's plenty of action there still.”

There are some caveats we must attach to this, which reflects the fact Allison effectively characterised this as a hope rather than a prediction.

Firstly, Red Bull’s dominance last year was founded in its race-pace advantage. This is harder to measure accurately, but often it was crushing last year and vastly stronger than its single-lap pace.

That’s thanks to design decisions that made qualifying more difficult thanks to struggles getting the front tyres up to temperature. Red Bull will aim to improve that this year, but it won’t sacrifice race pace for qualifying speed. This means that the single-lap performance figures referred to above only tell part of the story.

And given the RB20 that appeared at launch, there is the question of what Red Bull has in reserve. The combination of its dominance and its restrictions on aerodynamic testing last year means there are fears it has plenty of potential to deploy on this year’s car.

After all, given its strong position last year, it could afford to focus plenty of its limited aerodynamic testing on the 2024 car, hence McLaren team principal Andrea Stella saying “the question is have they cashed in accumulated development that they will capitalise” on.

Red Bull technical director Adrian Newey was at least dismissive of the notion Red Bull could afford to rest on its laurels.

In acknowledging that the grid had become more confined in 2023, he said: "[We] had to push right over the winter, we've made some improvements to the car in all areas. Mechanical, vehicle dynamics and aerodynamics.

"Is that enough? Who knows. That's the thing about Formula 1, we know roughly what we've done from the shakedown at Silverstone. It's behaved as we expected it to.

"But that's no guarantee of anything. It could be that some other team has done a bigger jump than us, we shall have to see."

That's no indication Red Bull necessarily expects to have the upper hand over its rivals, but it does suggest Newey feels there's ample room to extract more performance yet in this ruleset.

While it’s impossible to know where the performance ceiling of these cars are, it is there somewhere and Allison is right to argue that it’s likely already having an effect in limiting the development potential for Red Bull.

But only once the cars get on track in 2024 can we test that hypothesis and understand whether or not it’s enough of a factor to ensure that the fight at the front is as close as most F1 fans will hope.