Up Next

This Formula 1 season was meant to be a fresh start for Mercedes, one where it would finally eliminate the Achilles’ heel that’s held it back time and time again in this new ground effect era.

But it still hasn’t got on top of one of the key challenges of these ground effect cars and it’s hitting problems that are all too familiar.

This has to strengthen doubts over whether the dominant force of the 2010s will ever get on top of these types of cars.

What Mercedes is lacking

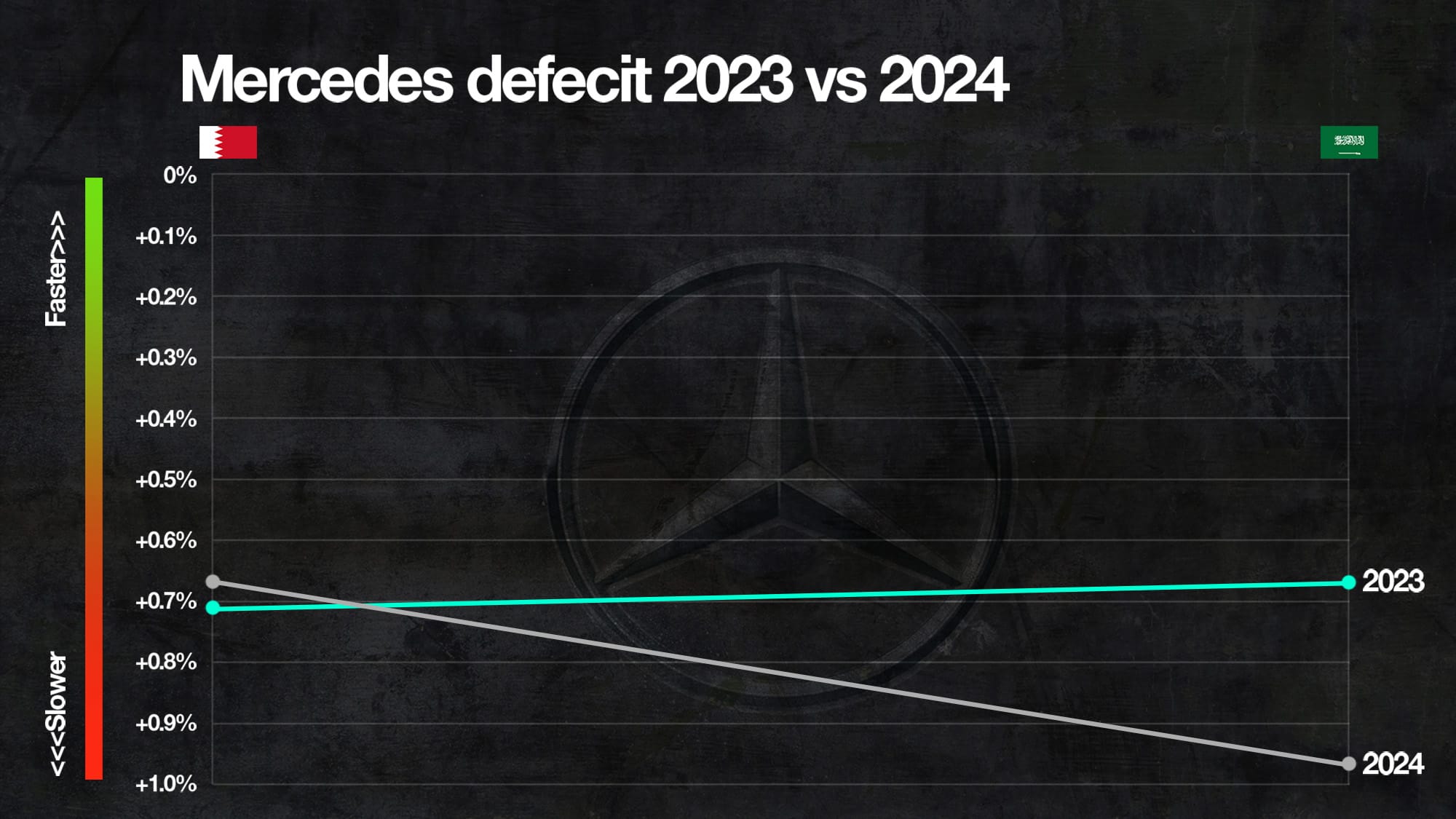

Mercedes has only been fifth fastest on single-lap pace in 2024 so far and still has a sizeable deficit to Red Bull.

That in itself isn’t the big concern because Mercedes always knew it would be off the pace of Red Bull at the start of the year. But the key objective was to have a car that worked consistently and performed in line with what the team expected.

In Bahrain, that seemed to be the case despite cooling problems that compromised Lewis Hamilton and George Russell's race pace. But in Saudi Arabia, some very familiar complaints emerged.

Hamilton was surprised, and likely bitterly disappointed, to discover during practice that, just like last year, he was “lacking a little confidence in the rear of the car”.

The problem persisted throughout the Jeddah weekend, with Hamilton even experimenting with a higher-downforce rear wing in FP3 to try and solve the problem.

“There’s a bigger factor with the lack [of pace] in the high-speed [corners] than just the rear wing,” Mercedes boss Toto Wolff said.

“We’re missing downforce beyond the steps we would have with a bigger rear wing. We tried it on Lewis, some tests, which we don’t understand. We are quick everywhere else, pretty much.”

Thanks to these struggles, while Mercedes had been a little closer to the pace in qualifying in Bahrain this year versus last year, it was substantially worse off in Saudi Arabia.

To get the performance out of these ground effect cars at a smooth, high-grip track like Jeddah, you need to run the car low and stiff. And this is where Mercedes is, yet again, hitting trouble.

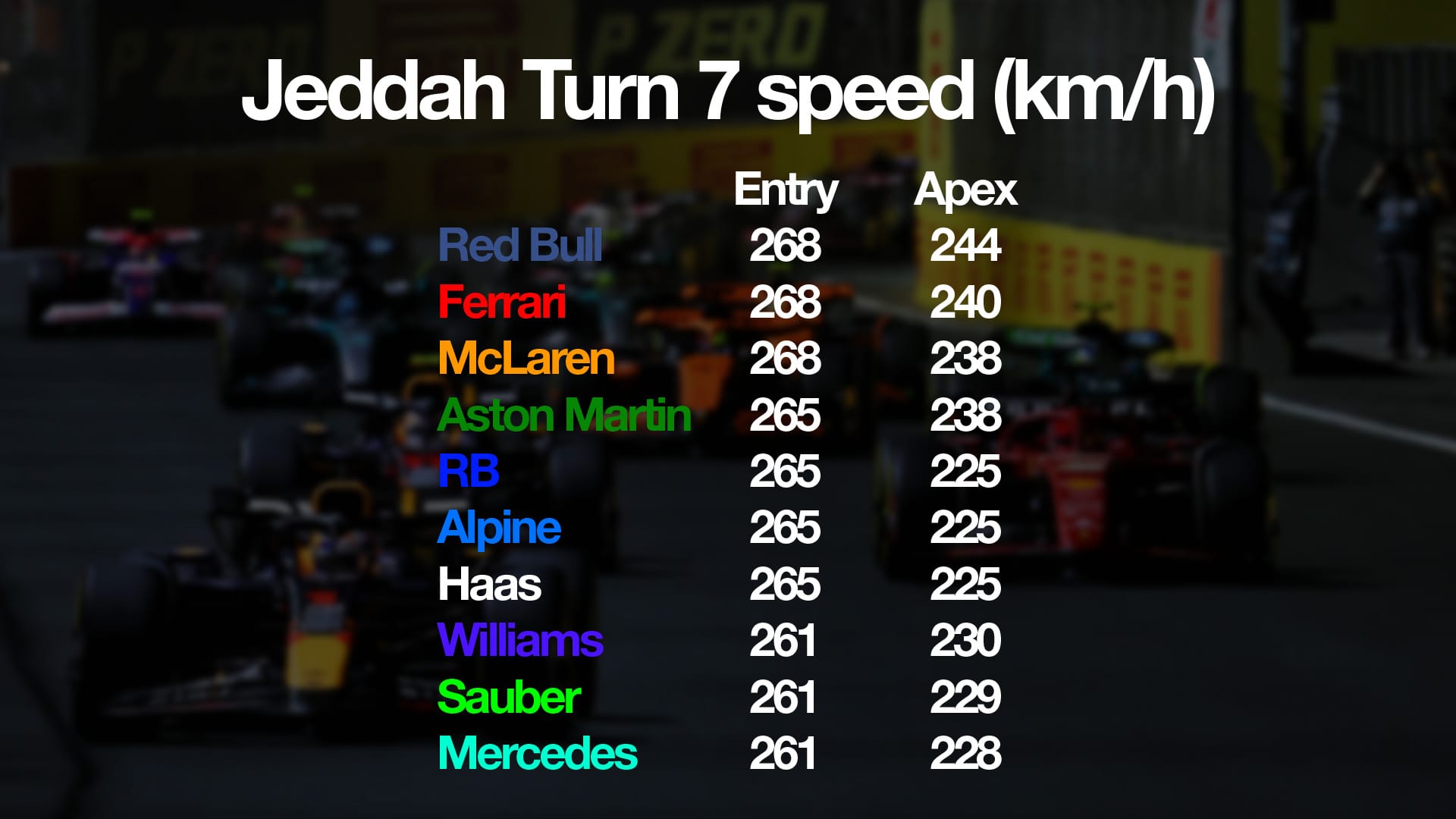

A glance at the performance of the cars through the high-speed sweeps of Turns 6 to 10 at Jeddah highlights the difficulty.

This is a challenging section of the track for the car and the Mercedes W15 was the slowest of all in qualifying at the entry to Turn 7 where it was 7km/h slower than Red Bull, Ferrari and McLaren. At the apex, the Mercedes gave away 16km/h to the Red Bull.

When The Race asked Russell after qualifying how concerned he was that there might not be such a sweet spot for the car, he replied: “We’re learning about the car and we just need to find a better compromise here.

“We’re chasing the downforce but perhaps the downforce isn’t worth the losses that the bouncing brings.

“We’ve shown really strong pace at points. We went out in FP1 yesterday and we were quickest on the hard tyre straight from the get-go. And then it seemingly got slower.

“In Bahrain we were really quick on Thursday and then on Friday we seemingly got slower.

“We still need to get on top of it and maybe we just need to strike a different compromise.”

Indeed, the compromise clearly wasn't right in qualifying in Jeddah - with Russell saying he “couldn’t get through the high-speed without clouting the ground".

"I turned in, the car hit the ground and I went off because I was going through the corner maybe 10km/h quicker than at any other time this weekend,” he added.

This has echoes of what Mercedes has battled for years. The inconsistent performance, the unpredictable swings from day to day and even between the two sides of the garage, as well as the struggles with getting the car to do what is expected in the faster corners when running close to the ground.

And worst of all, this is something the team believed it had got on top of. In Bahrain, Russell spoke of his certainty that this problem with lack of confidence in the rear end had been solved and that Mercedes had a much better platform to work from.

Admittedly, it’s clear the problem isn’t as bad as it was before. It’s only in specific corners where this lack of confidence, which comes from a lack of downforce, manifests itself. But it is clear that a problem Mercedes believed was behind it persists.

As head of trackside engineering Andrew Shovlin explained, Mercedes was battling three main issues in Saudi Arabia. Firstly, the poor balance meant the car often suffered snaps of oversteer in the high-speed corners. Then, Shovlin also confirmed that bouncing was a problem, primarily in qualifying.

But the main difficulty, he indicated, was simply not having enough grip.

“Fundamentally the limitations that we had in qualifying and the race were broadly the same for both cars,” Shovlin explained.

“So it’s telling you it’s not a small difference [change], it’s not a tiny bit of camber or a spring or bar here and there. It’s something more fundamental that we need to dig into and understand.”

A fundamental problem

So what is going wrong and what exactly is that fundamental problem? Well, as mentioned above, it’s clear that Mercedes is hitting trouble at high speed when the car is pulled close to the ground by the powerful venturis in the underfloor.

When it comes to ground effect cars, the closer to the ground you are the more downforce you generate. But you don’t want to hit the ground or you run the risk of triggering bouncing or porpoising.

This is why the suspension of these cars is so important. Ideally, you need a mechanical platform that holds the car in the right place to generate that downforce without being too stiff to be compliant enough to drive. That’s a sweet spot Red Bull is brilliant at achieving.

However, simulating that in the design and development phase is not easy. You can’t do it in the windtunnel as you can’t have the car model hitting the belt. CFD is a valuable tool, but as the floor of the car gets close to the ground the calculations become exponentially more complicated.

Mercedes has been working on improving its simulation tools ever since it realised it was in trouble in 2022, so this is an area where gains have been made. But, according to Wolff, it’s not enough.

“Our simulations point us in a direction and this is the kind of set-up range we then choose,” Wolff explained.

“You put the right rear wing on and then I think you gain a few tenths or not if you get the set-up right.

“It’s not a massive corridor of performance. It’s more from the mental thing that we believe the speed should be there. We measure the downforce, but we’re not finding it on the laptime.”

So we’re into the question of correlation here. There’s a point where the downforce isn’t produced at the levels required to give the car the grip it needs, which in particular manifests itself as a lack of confidence in the rear end. And that confidence is lacking because the overall grip is not there.

“We had so many unknowns in the last year where we start, OK this could be a reason and this could be a reason and this could be a reason - and we fixed that,” Wolff said.

“I can see from the sensors that we have what we needed. But there is still this behaviour of the car in a certain speed range that our sensors and simulations say, ‘This is where we should have the downforce’, and we are not having it.

“This team has not been overconfident - we are probably the other way around and see the glass half-empty always, and that attitude stays. But this attitude is also the attitude to fix it.”

And Wolff is certain Mercedes will get there.

“Is this good enough to beat Max [Verstappen] in a Red Bull?” he said. “No, it’s not, but at least bringing ourselves back in a position of fighting for podiums and being right there, yeah… 100% sure we’re going to get there.”

Now, the team must, according to Wolf, give it a “massive go” in the build-up to the Australian GP to understand what can be done. The high-speed left/right of Turns 9 and 10 in particular will be a time-sapping sequence if Mercedes is still hamstrung.

The problem is, if the source of the weakness is the simulation tools the team has been using, tools Mercedes has been working on sharpening for more than two years, can it really be expected to turn things around immediately?

The silver lining

So does all this mean 2024 is set to be another troubleshooting-filled year that requires major changes that can’t be made until the winter? Not necessarily.

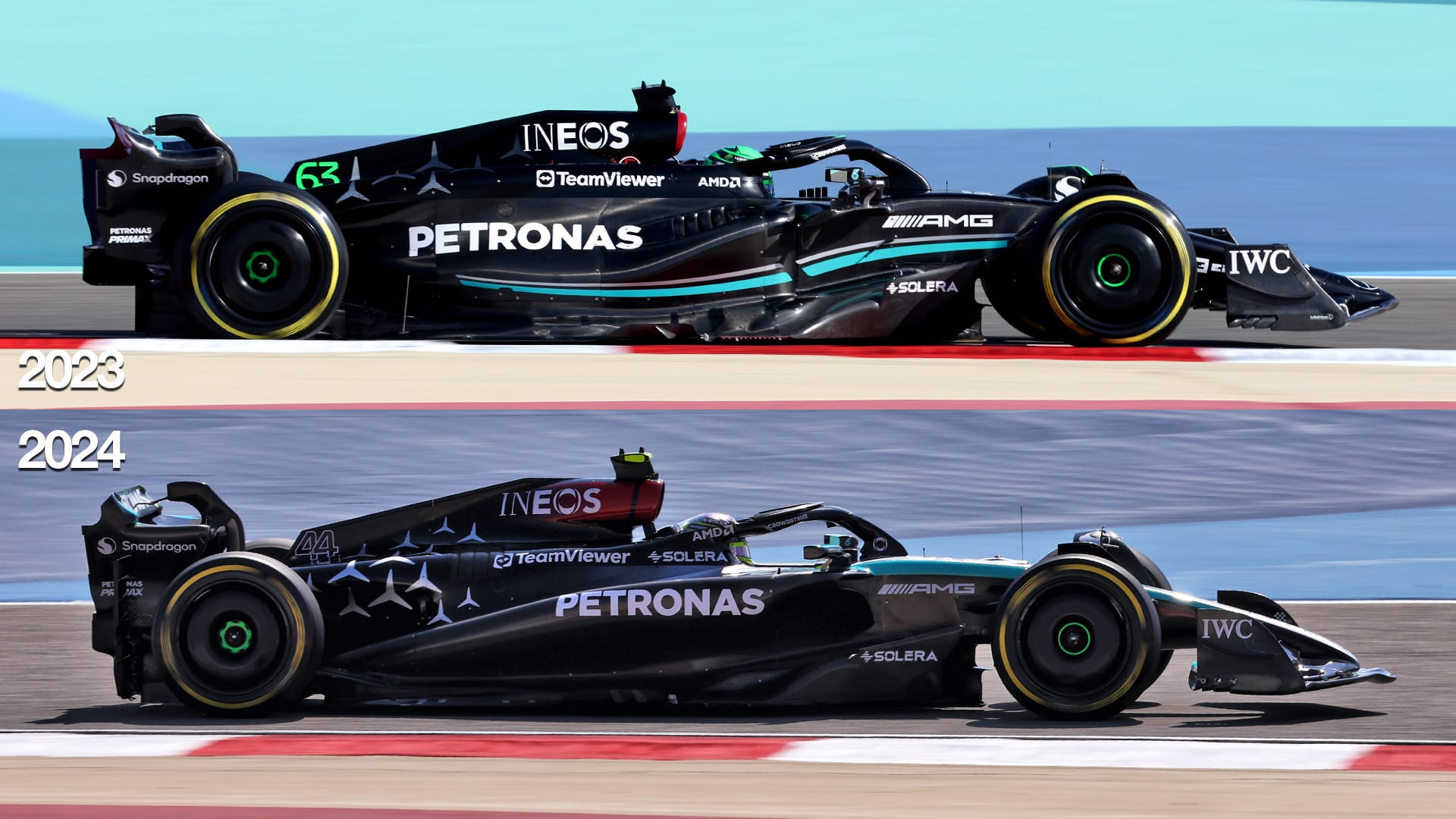

Mercedes made some major changes to the architecture of the car for 2024 with a revised monocoque, which included moving the cockpit rearwards by 10cm, and a revised rear suspension and gearbox. These were hard points in the design that needed to change to create more performance potential.

But the 2024 Mercedes problem presumably lurks in the detail of the floor. And that primarily means the topography of the hidden underfloor.

When you are at high speed and the car is close to the track, you don’t want the downforce to keep building endlessly or you will suddenly be on the ground.

Therefore, you want to design your floor so that there’s a small, controllable stall effect that will prevent the car from being pushed lower. However, you don’t want this stall to be too big or you risk the car rising and porpoising beginning.

This is fiendishly difficult to do and is potentially what is eluding Mercedes. The fact Wolff talks about the car not producing the downforce anticipated in the high speed suggests that perhaps the attempts to control this are not working as expected.

Whatever the problem is, it requires an enormous depth of understanding to eliminate and, from the outside, you can only point to the possible problems in general terms. The fix will lurk in the detail.

If it can’t be solved with tweaks to the set-up and the way the car runs, which seems unlikely, Mercedes will surely look to the shape of the underfloor and perhaps the detail of the floor edges to tackle this.

If it is primarily an aerodynamic problem, then that is fixable - assuming Mercedes can understand it.