As Formula 1’s on-track complexity has come on in leaps and bounds over recent years, the FIA followed suit in ramping up its own systems and technology to police everything.

With everything now under scrutiny to the tiniest of degrees, there is no room to get things wrong nor miss vital rules transgressions where quick decisions have to be made.

Where once it may have been acceptable for stewards to wait until some video footage of incidents had been obtained hours after the event before making a call - or even not being aware of some blatant rules breaches because they were never spotted by cameras - things are very different now.

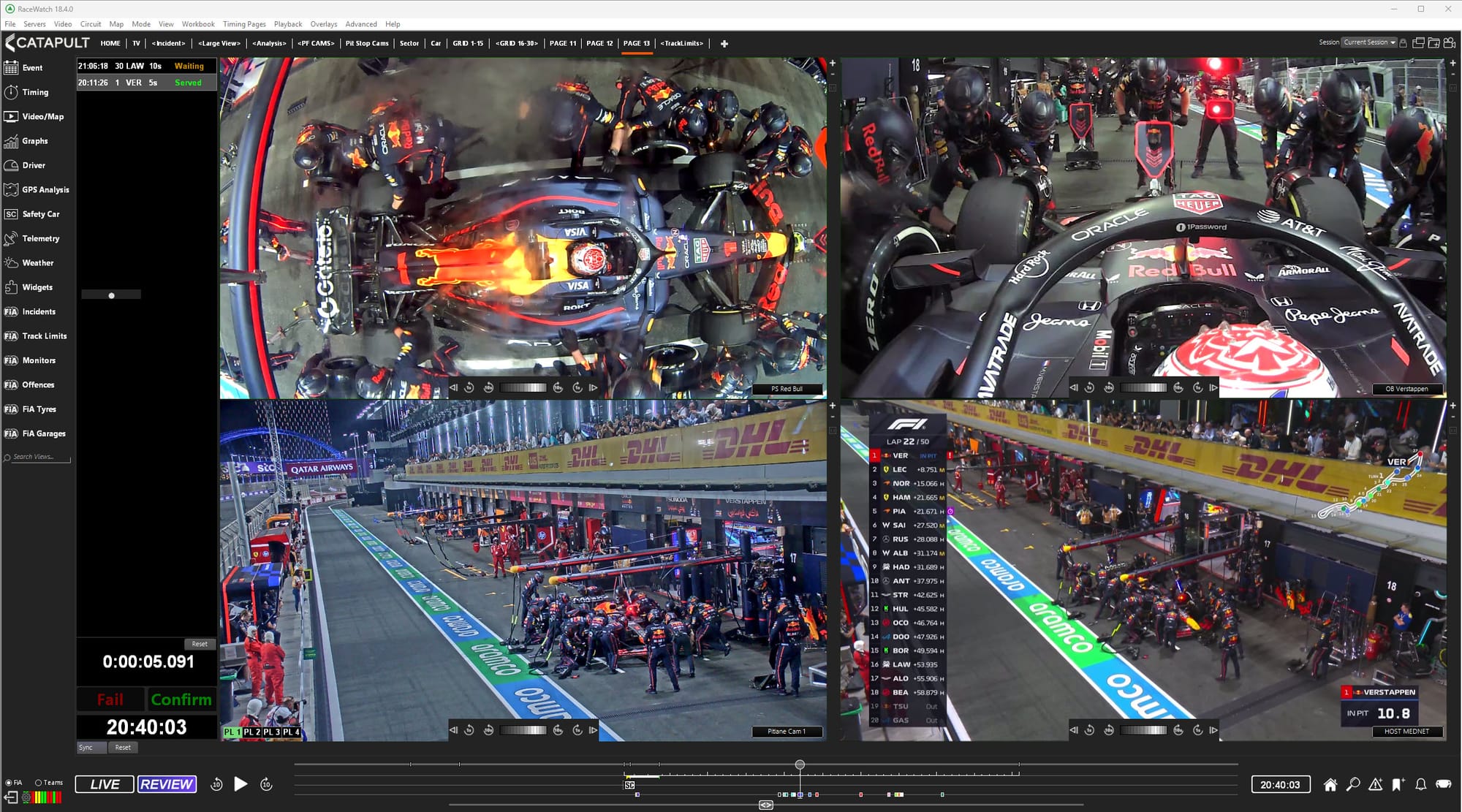

The Race has been behind the scenes to see first-hand how the FIA’s ever-evolving race management platform - known as Racewatch - is used to deliver the right information and images to the relevant people in race control and the stewards’ room.

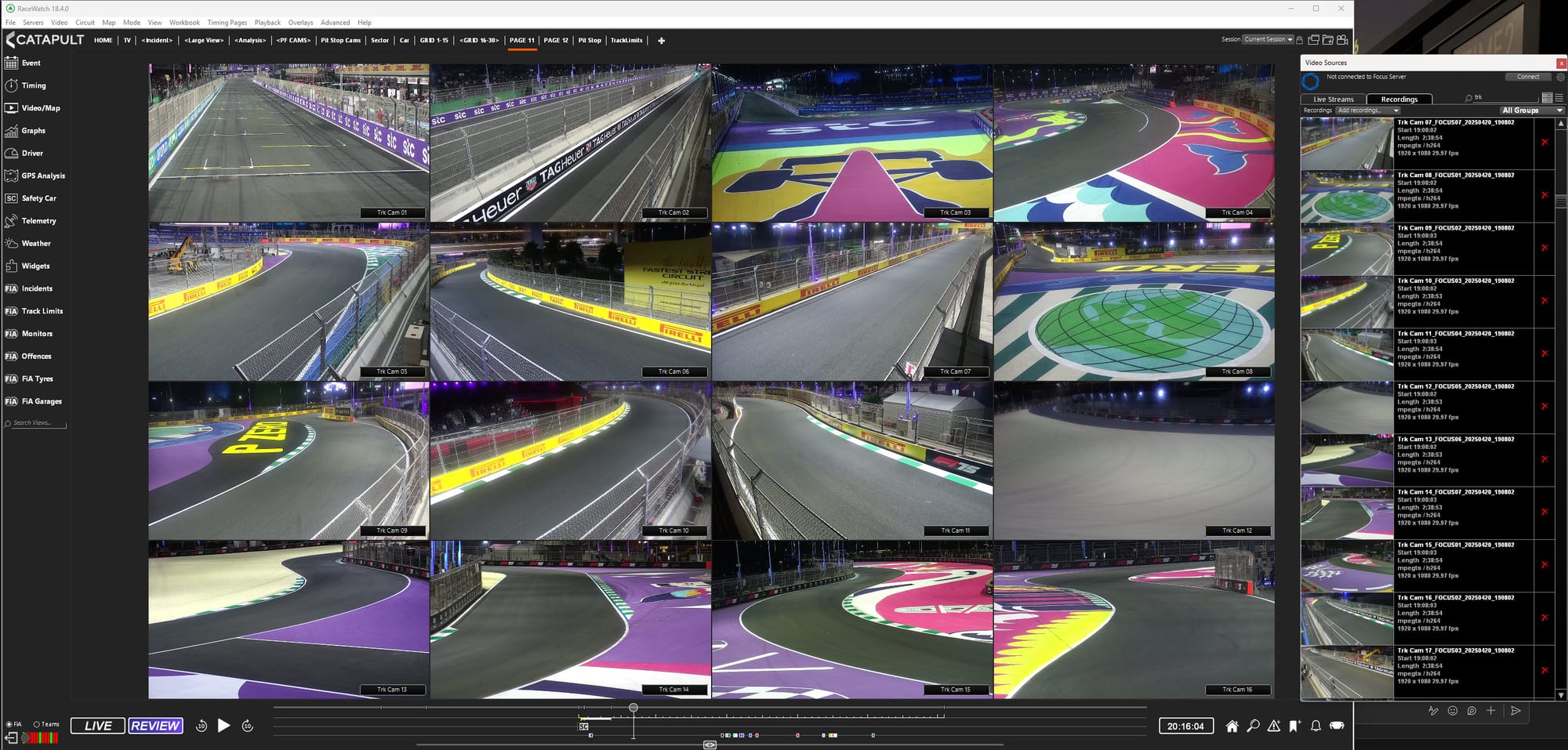

The system makes use of all the CCTV cameras around the track, which means a total of around 60 feeds plus those available from cars, to bring an all-encompassing viewpoint of everything that is happening even when the main international feed is not watching.

Add to that 30+ intercom channels and more than 300 sensors on cars transmitting data every millisecond, and all the information that the FIA could ever need is at its fingertips.

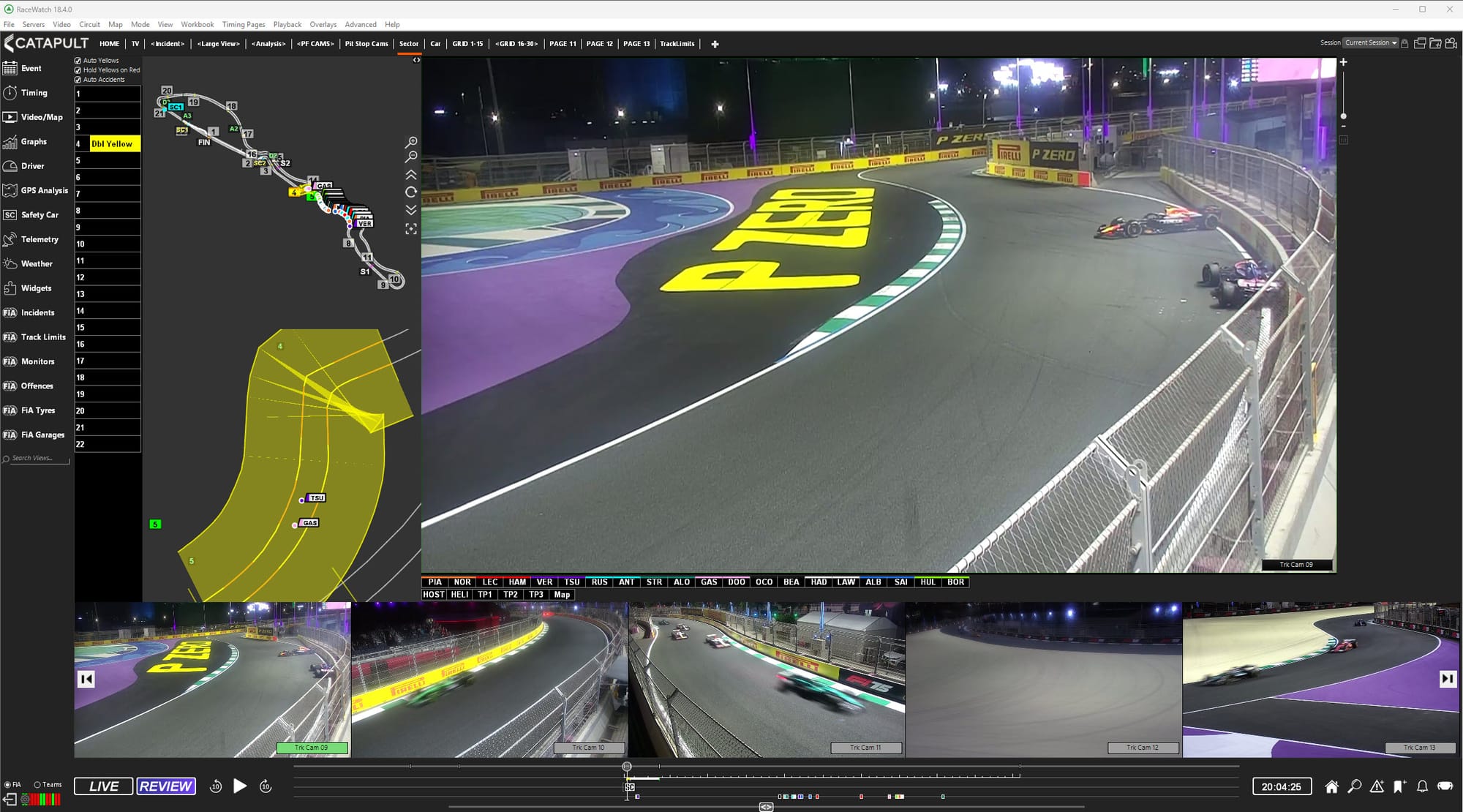

The system also responds to incidents, so when there is an accident or a yellow caution flag, then it will automatically display the areas of the track with all the cameras to help race control get a better grasp of what is happening.

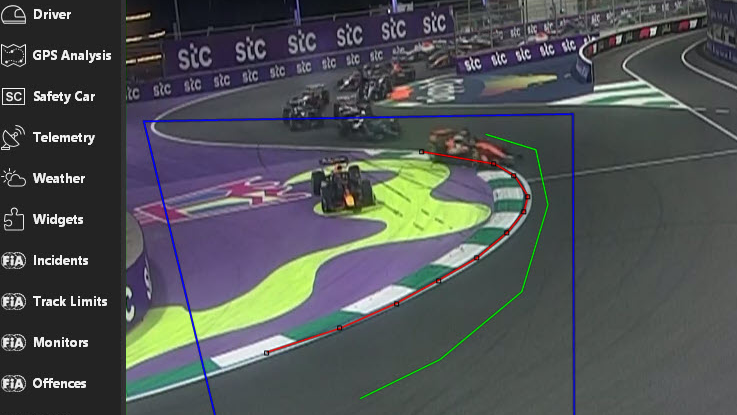

This can be seen below which shows what race control had available to it after the Yuki Tsunoda/Pierre Gasly collision on the opening lap of the Saudi Arabian Grand Prix.

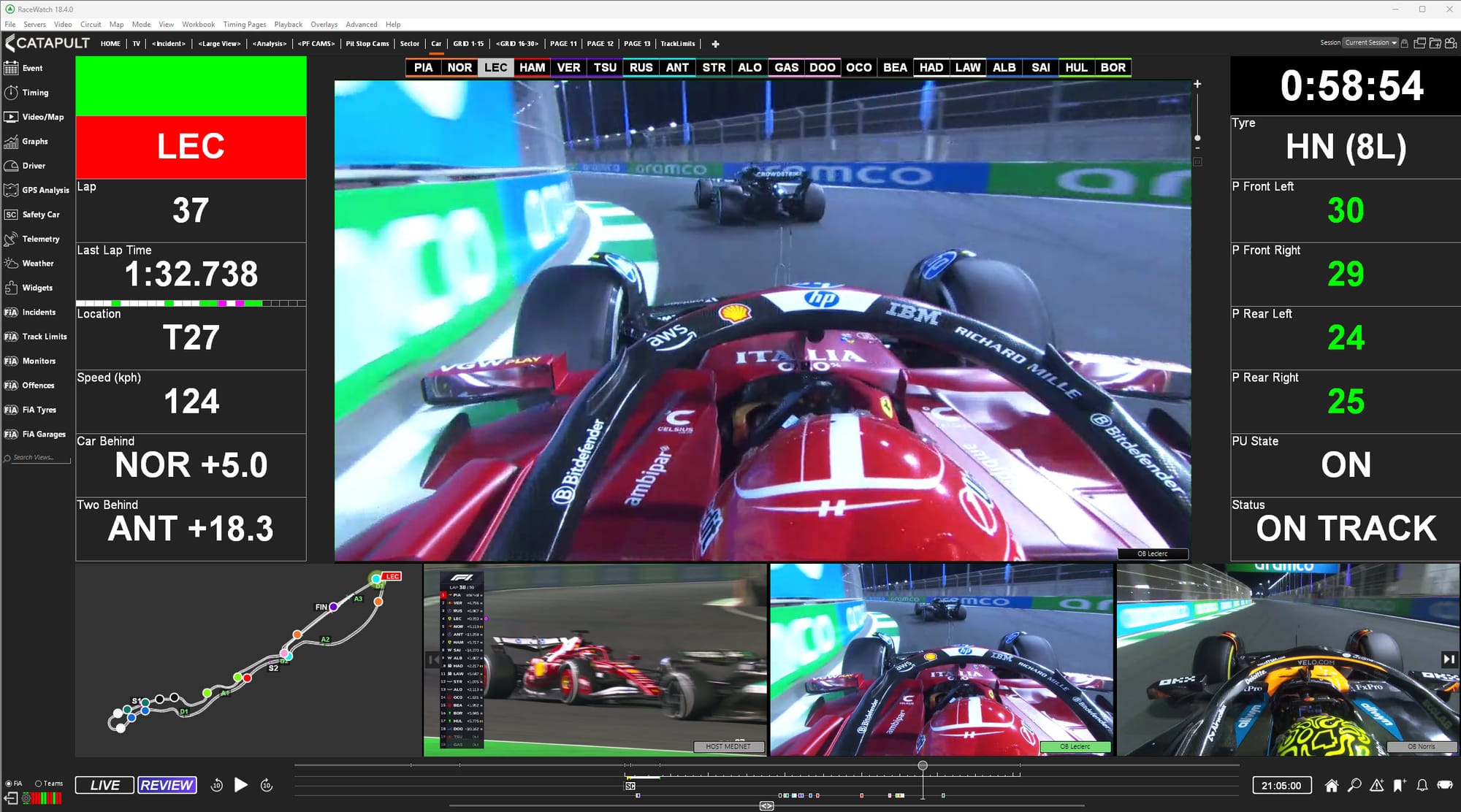

Individual cars can also be singled out so the FIA has access to the full data of what is going on with them and around them.

The flexibility of the system allows for proper management of incidents, the best information being made available to race control when it comes to safety critical decisions, and also access to instant footage and data when the rules are broken.

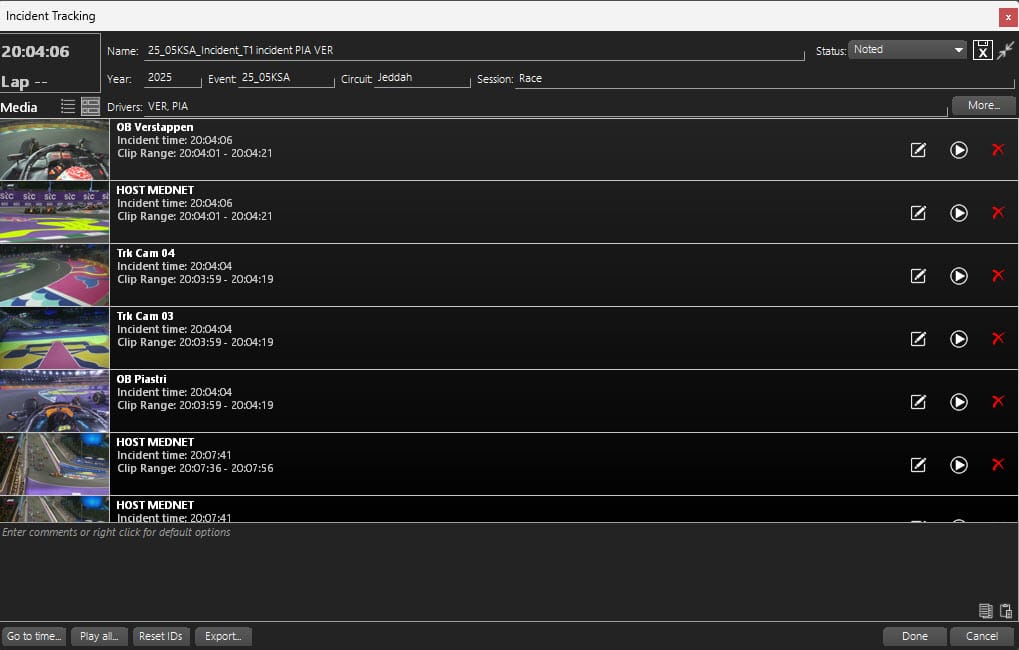

Anything that is detected as potentially being an incident - and these can be alerted from race control, teams, the FIA’s Remote Operations Centre or even the stewards themselves - automatically gets put into a folder where all the relevant video, audio and data files can be accessed in an instant.

A better way of doing things

The system, which is overseen by Chris Bentley, the FIA’s Single Seater Head of Information Systems Strategy, and has been developed in cooperation with Australian sports technology solutions company Catapult, has been in place for around 15 years now.

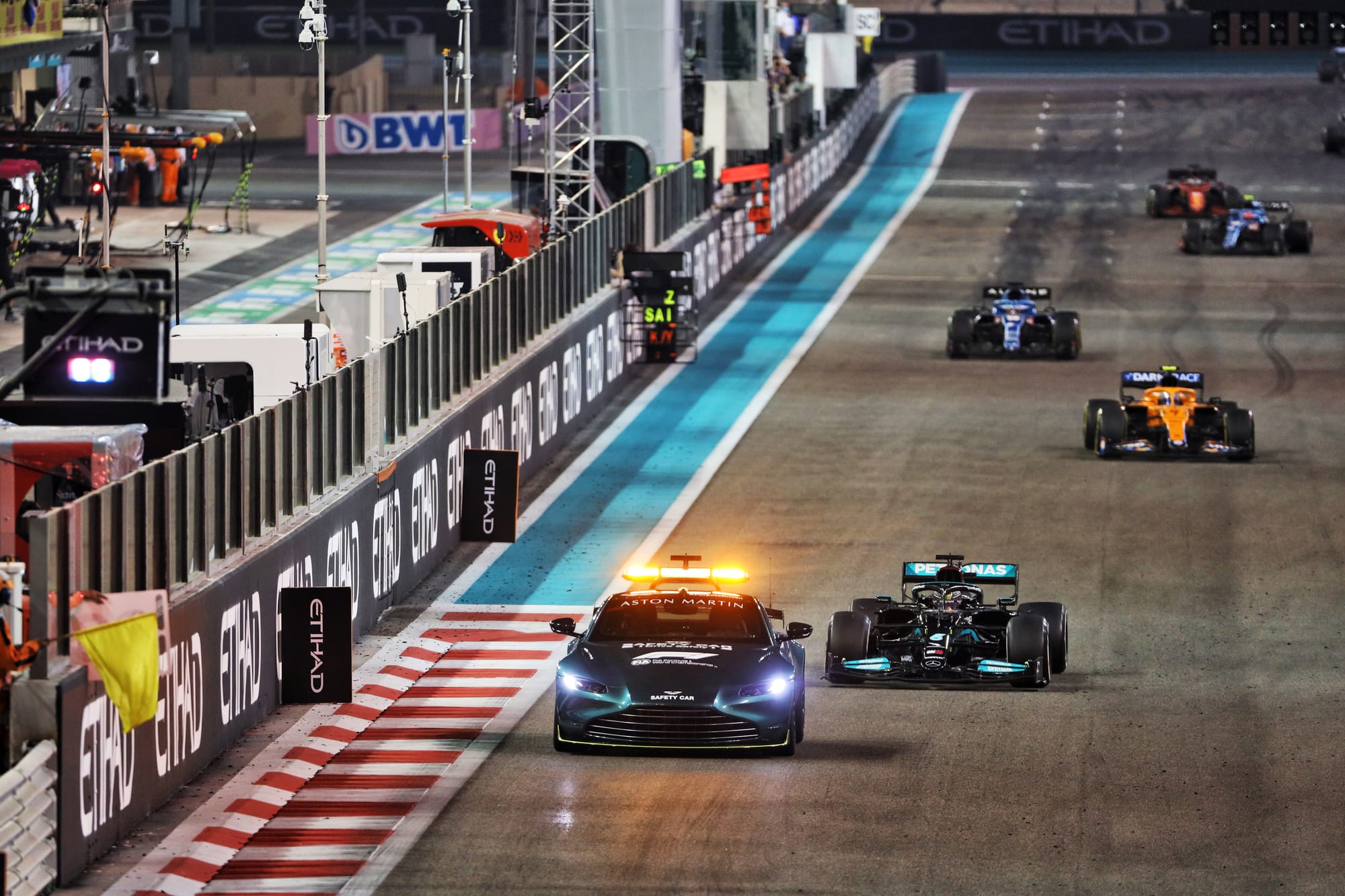

The idea for something as all-encompassing as this has its origins in the aftermath of the 2007 Japanese Grand Prix (pictured above), when old ways of doing things no longer seemed good enough.

Back then, for example, the FIA used a simple email messaging system to communicate with teams - but this hit a snag when then Ferrari team principal Stefano Domenicali did not receive a communication about the type of wet tyres his cars needed to start the rain-hit race on prior to the action getting going.

Relying on emails and people then seeing the messages was clearly not a sustainable way of doing things, which is why the FIA started work on its own backroom system to put everyone on the same page.

As Tim Malyon, the FIA’s safety director told The Race: “I would say things have moved on.

“We've been investing in technology to provide us more space and information for good decision making, and that's an ongoing process of continual improvement over a number of years now."

One of the key aspects is in making sure that the right information is available at the right time so there is not a data overload.

Malyon likens it to how aircraft systems feed information to the pilot but want to avoid giving them so much data that they are overwhelmed.

“If everything's going well, does the pilot actually need to know anything?” he said. “Do you need to be displaying a huge amount of numbers?

“In a very similar way in race control, where we have a huge amount of data coming in, so it's about optimising the technology to interact with humans in the best way possible.

“If all's going well, we don't necessarily need to be monitoring everything. But if you can set up widgets, triggers, and automated analyses that provide pertinent information at the right time, it allows you to optimise the people in race control as well.”

Learning from errors like Abu Dhabi 2021

Of course, nothing in life is ever perfect and despite all the efforts to create the best systems, things can go wrong and errors are made.

But that is part of the learning process, and the means by which the FIA’s race management system has become better over the years because lessons are taken on board and improvements made.

As Bentley explains: ”It is always under development. We're always learning and changing and adapting.

“It's not as if the FIA sits there and doesn't listen and doesn’t want to adapt. We look to do better and we also work with the teams to make this all fit together for everybody.

“If there is an issue, we learn from it so that next time there is not going to be an issue.”

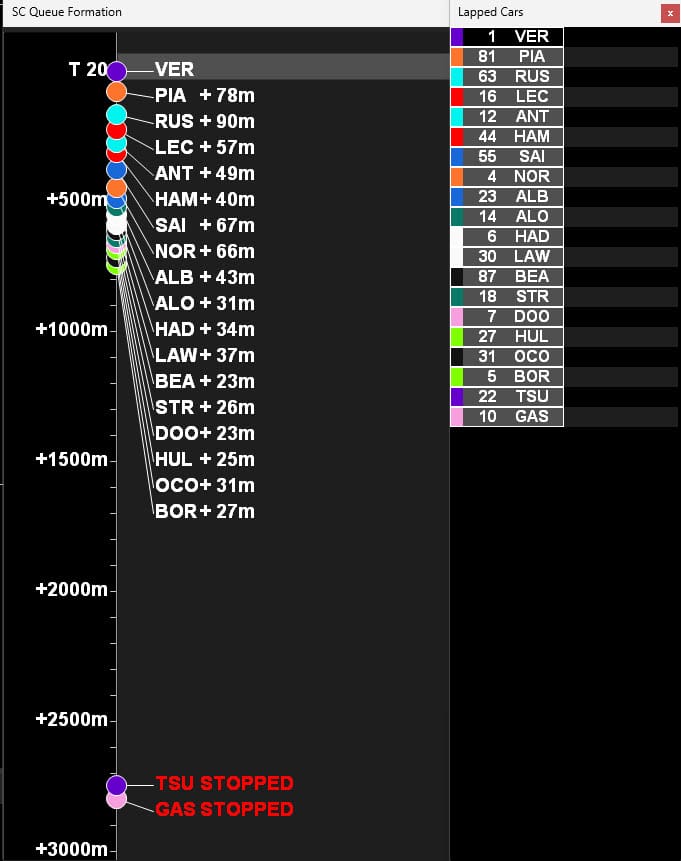

Some of the lessons can be quite big, with the famous Abu Dhabi 2021 race highlighting that, under pressure, errors can be made by humans when it comes to trying to work out which cars are lapped behind the safety car.

As a consequence of the mistake in not getting all cars unlapped that day, changes were made to use the technology available.

Now the FIA’s system is programmed to display a widget where the safety car queue is displayed with car gaps, it highlights those that are lapped, the stopped cars and those in the pits.

By tracking the lapped cars, the system can create an automatic list that can then be broadcast on the relevant race control message to teams so they can unlap themselves.

The delta element is also important in helping race control better understand where cars are on track.

This could help avoid the situation like at the 2023 Japanese Grand Prix when Gasly was trying to catch up with the safety car queue at the moment the race went into red flag conditions, and went at speed past a recovery vehicle on track.

As Bentley explains: “These are all the different widgets and things that we've added over time to be able to enhance things. And we're adding things all the time, modifying them and improving them.”

Responding to problems

It is not just in improving systems, or changing some software, where progress is made

When problems crop up, the FIA sees if there are different ways of doing things or even if the rules need changing.

Malyon cites the example of Lando Norris not getting penalised at the start of the 2024 Saudi Arabian Grand Prix for a jump start after his transponder had not detected it.

The stewards had video footage of the car moving but, with the rules dictating that jump starts could only be judged based on the transponder, it was unable to hand a penalty down.

It was not the first time such an issue had cropped up with the transponder failing to pick up false starts, so the FIA was prompted into action.

Malyon explains: “We made investments in technology, which is when you started to see extra cameras appear on the grid.

“We evolved our systems to be able to look at that more explicitly, more cleanly, more clearly, and have more data. But on top of that, the technology evolves, but the people also evolve as well.”

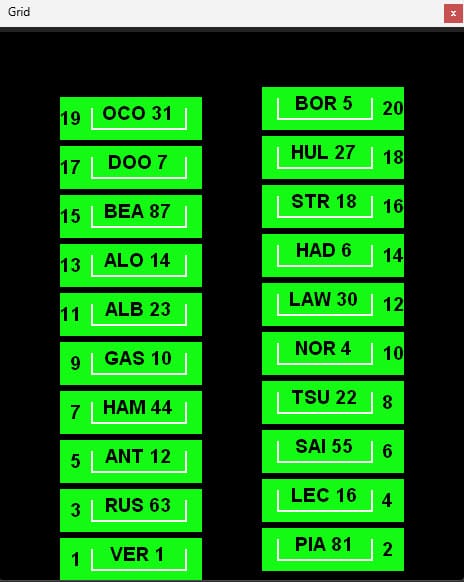

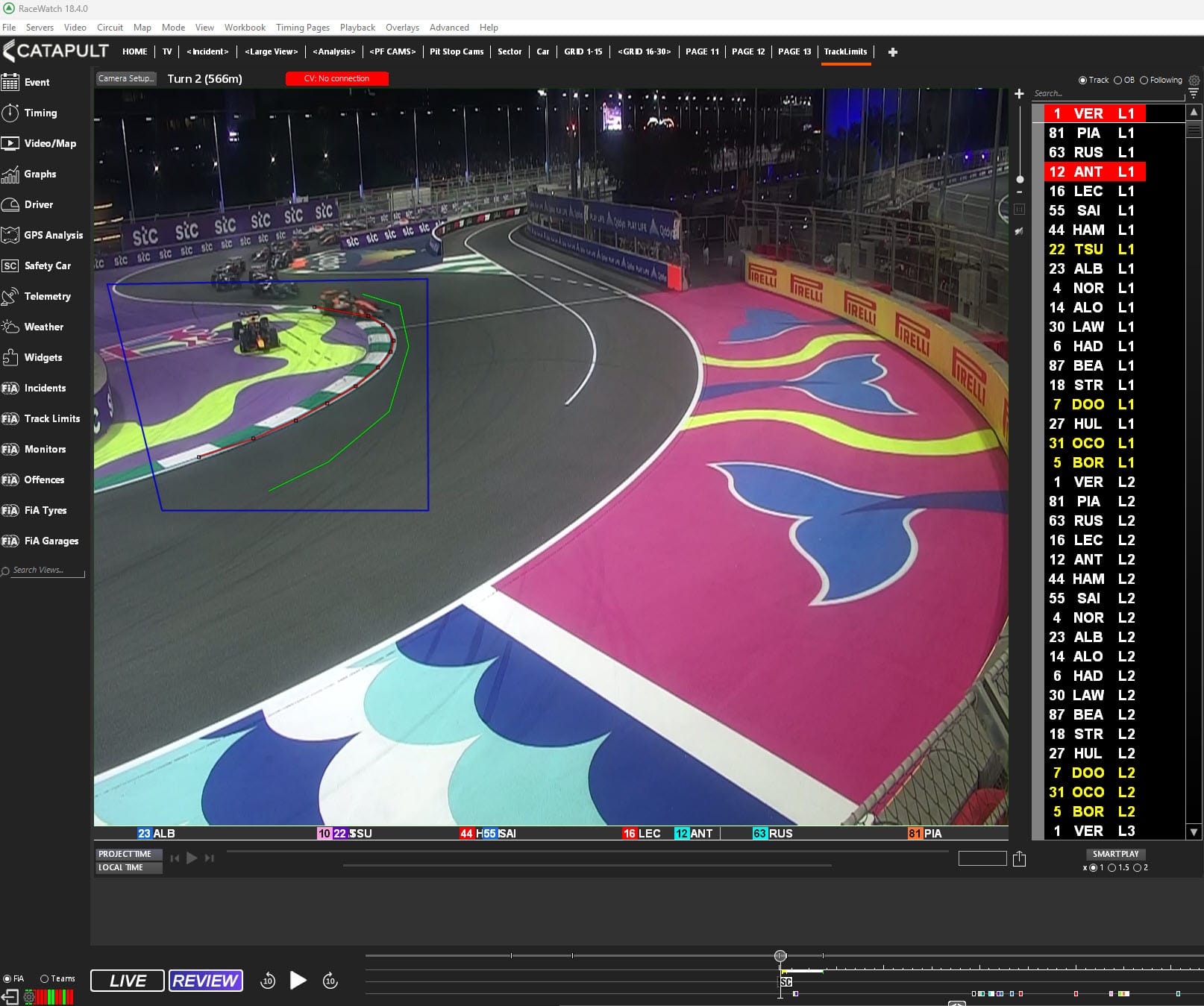

With extra bespoke cameras now monitoring the starts and positioning of all cars (see below) which are downloaded as edited files and available to race control and the stewards just seconds after the lights go out (it takes 40 seconds to create the entire folder) - getting away with a jump start is now almost impossible.

The system proved good enough for the FIA to change its sporting regulations to get rid of the requirement for a jump start only to be counted if the transponder detected it.

An automatic grid monitoring widget also ensures that race control is aware of which drivers are in position before the start, and whether or not there are any subsequent problems that could trigger a delay.

Extra cameras have also been introduced to help monitor whether or not cars serve their penalties in the pitlane - after problems in the past of there being questions about if this had happened properly or not.

While more robust monitoring on this front has not been entirely trouble free - as Carlos Sainz’s missed penalty serving from Bahrain showed as he was briefly handed a grid penalty for the following race before it was rescinded - each time there are stumbles, the FIA looks into it and puts in place solutions to minimise the chances of a repeat.

Malyon adds: “Like all technology in this sport, for us it is an evolving target. But we do our best to achieve continued improvement and work on the areas of the system that we need to. It continues to expand week on week, year on year.”

The use of AI

The FIA has been exploring ways to make better use of artificial intelligence to help it in the policing of various aspects.

And the most obvious - but not only area - is in dealing with track limits.

With it being unrealistic for proper policing of track limits to take place by manual checking of video feeds of every car over every lap of an F1 weekend, the help that can be given by bringing some automation in is obvious.

The FIA’s work with Catapult has created a bespoke positioning system that allows for AI involvement in deciding whether or not cars were outside track limits.

Known as Track Limits Computer Vision (TLCV) and now integrated into Racewatch, it helps define where the track edge is (as can be seen plotted on the red line above) and the AI can then detect cars that appear to have gone beyond it.

For the first lap in Saudi Arabia, as can be seen in the log table down the right of the above image, the system flagged that Max Verstappen and Kimi Antonelli had crossed the red line.

But while AI technology has advanced a lot, the FIA does not want it to be making actual calls on close decisions so humans still need to judge on whether or not the rules have been broken.

As Malyon explains: “I don't believe we're at a stage where technology will make a decision. And in fact, for the fair and equitable nature in sport, I'm not sure we want technology to make a decision at this stage. What we want to do is use technology to optimise the human and the time they have available.”

Behind every F1 race is a live operating system called RaceWatch.

— Catapult (@catapultsports) April 30, 2025

Built with the @fia over 15 years, it tracks 300+ sensors per car, flags incidents in real-time, and powers race control decisions.

Now, it’s inspiring tech in football, rugby & more: https://t.co/4aiVOmaKCO… pic.twitter.com/917YDMqzqF

The concept the FIA uses is that AI can automatically discount those track limits breaches that are so obviously outside that they do not require human intervention. That will then allow it to flag up those more marginal cases where things are very close and getting human insight is important.

It means that FIA personnel only need to pay attention to 5% of track limits incidents that are flagged, ensuring those marginal calls get more attention.

Malyon (pictured below) compares it to using AI for medical scans.

“The conclusion they've come to is not that they want to use AI to actually diagnose,” he said.

“What they want to do is to use AI to exclude the 90% of cases where it's clear there is nothing to look at and allow the expert, highly trained operator to spend 100% of their time looking at the 10% of the cases to be able to make better decisions.”

Like every aspect Racewatch is now involved in, the FIA’s approach is to learn and evolve.

Bentley adds: “The software is under development all the time. This platform has been running for 15 years and there are not many things that have been running that long that have been constantly evolving in this way.

“Every race we are finding things, and we're monitoring it and adding to it and bringing together new tools. And we're already looking at other stuff in the future.”