Up Next

Had Mercedes and Ferrari not got their concepts wrong, McLaren’s season would likely have looked less eye-catching than it did.

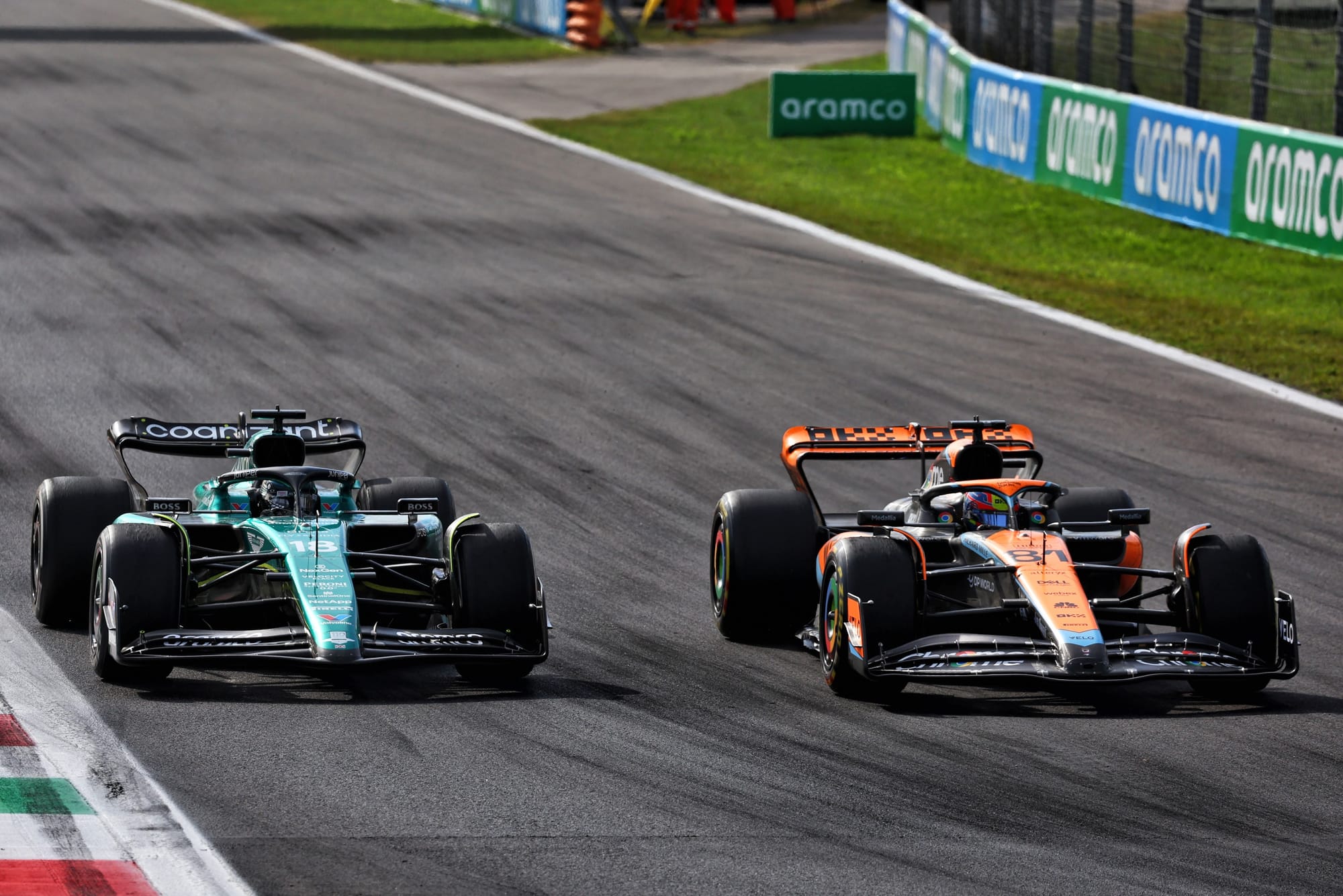

But it’s to McLaren’s credit that, unlike those two rivals, it saw which way the technical wind was blowing before the season had even begun. Couple that with the competitive collapse of Aston Martin after Spain and McLaren was something of a sensation. Such dramatic turnarounds in form are very rare in modern F1.

It started the year with a concept it had already realised was obsolete and based its whole approach on updating that – as far as was possible within the hard points of the chassis – as quickly as possible.

The second part of that critical upgrade came in Austria and that was the fulcrum upon which McLaren’s season pivoted. It leapfrogged the team past not only the midfield rivals it had been struggling against – but past Ferrari and Mercedes, too.

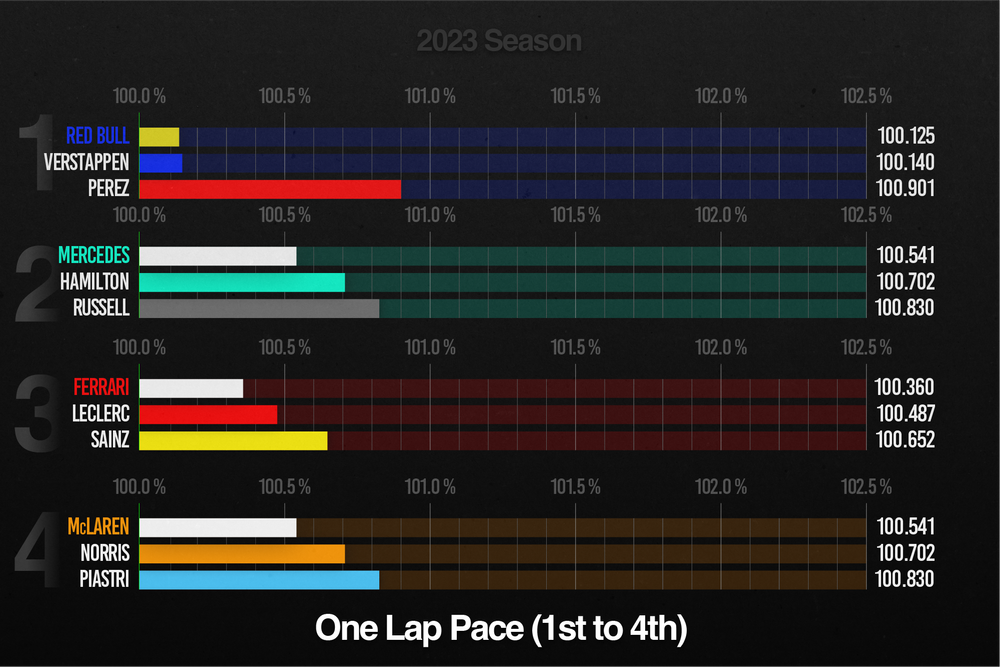

In the nine-race sequence between Austria in July and Qatar in October, the McLaren MCL60 was on average F1’s second-fastest car. It could even occasionally present a threat to Red Bull in qualifying – though not in the race.

The flurry of podiums – and a win for Oscar Piastri in the Qatar sprint - was enough to vault the team up to a strong fourth place in the championship.

It put the team on an apparently exciting trajectory, one which looked frankly unlikely early-season when the original car – which had missed the performance targets set for it over the winter - wasn’t even always making it out of Q1 and the technical director James Key had parted company with the team.

That was one of the first actions taken by Andrea Stella after being promoted to team principal to replace the Audi-bound Andreas Seidl.

In his previous position as performance director, Stella had felt the structure of the technical department placed too much managerial load on some of the design talent – specifically the aerodynamics chief Peter Prodromou.

In his new boss role, Stella encouraged Prodromou to devote more of his time to what he does best – which is creating and drawing in his search for aero performance.

Stella also recruited David Sanchez from Ferrari and Rob Marshall from Red Bull to bolster the technical team but their gardening leave meant that for this season Stella was effectively the technical manager as well as team principal.

But the realisation of the need to change the whole architecture of the car around the floor-sidepod area came even before these personnel changes had been made, as Stella explains.

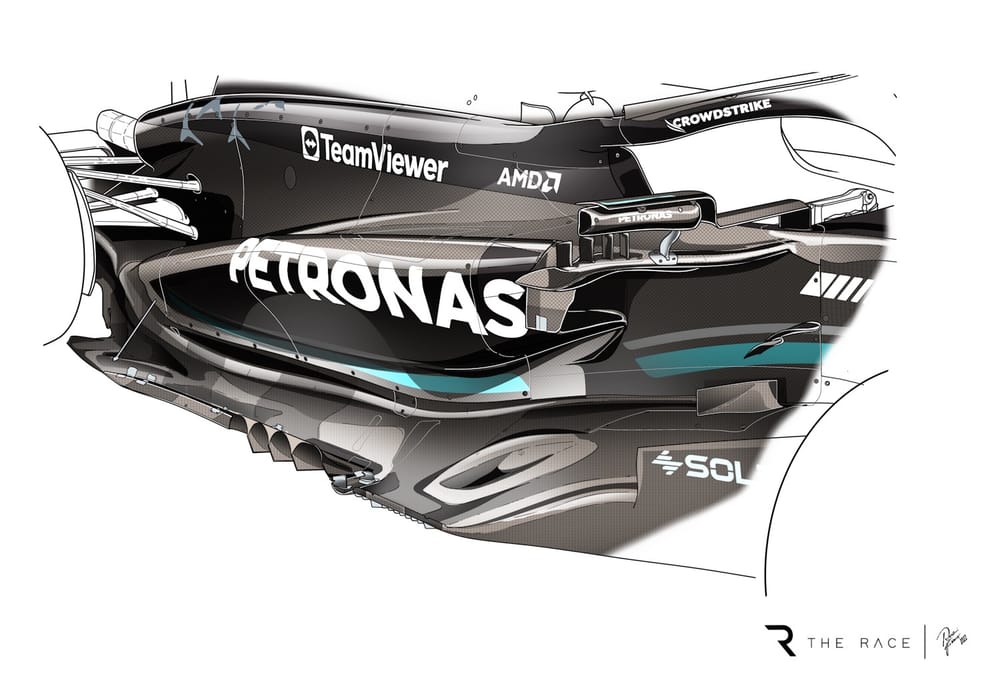

“The original programme was what became the launch car and which ran in the first three races. But looking at the geometry of that car, the floor especially, just from observation it did not seem to represent the new thinking on aero concepts we were already seeing on the top cars [of ‘22].

“So we began to look at those other concepts but they were not progressing very fast. In the tunnel, CFD, the aerodynamic tracker was just not progressing in a way you know by experience what is competitive.

"The slope was too gentle.”

With the newer – more Red Bull-like – concept not matching the performance of the original in simulation, the decision was taken to launch with the original and work at bringing the performance of the newer concept up.

By the time of the launch, that simulation breakthrough had finally been made and the team was already well underway with making what was effectively a B version of the car, with a fairly comprehensive redesign and re-engineering programme around the sidepods and floor.

The update came in two parts – the new floor of Baku and the new sidepods of Austria. Combined, they transformed the car.

Making it happen required some brave calls from Stella in his new role, but he’s big on collaborative skills and he felt he had a lot of talent within the team which could make his vision real. “We needed to unlock this potential from a flow physics point of view [to get the concept working] in the first place and technical point of view [to get it designed and built] in the second place,” he recalls.

“Even the technical knowledge requires the people element. You may have seen technical people who may have been very strong technically were horrible to work with and normally this does not lead to sustained success…

"You can be illuminated in terms of technical knowledge but if you don’t get the 100 people in the aero department to follow you, understand your vision, to believe in it, it’s always a bit of a threat when you introduce a new aero concept.

"It’s not like the day after you switch it on and it works. The day after is, ‘Mmm, I don’t know. It's promising but there are many downsides and, by the way, the car is now slower than it was yesterday'.

"So that is where you need to buy the trust of your people, to buy it because of the validity of the technical concepts but also because you kind of activate the human elements which create a team.

"That’s where we were in around December ’22; we realised the geometry was what it was while for a few weeks we observed the tracker [on the new concept] was not going very steep and we felt there was potential - but how do we unlock it?”

It’s to Stella’s great credit – and of the group which bought into that vision – that they pulled the turnaround off. Comparing its pre- and post-Austria qualifying deficits to pole, the car gained around 0.85s to the front, an enormous leap.

That much was in McLaren’s own control and it did what it did. What was not in its control was where that would put it on the grid.

Pre-Austria, it was the sixth-fastest car (barely ahead of Williams). Post-Austria it was the second-fastest – and that was partly down to the Ferrari and Mercedes concepts reaching the limit of their potential.

In hindsight, those teams had chosen wrong and struggled to make any inroads towards Red Bull.

Meanwhile, Aston Martin had what appeared to be a Red Bull-like concept - but after proving very fast for the first few races suddenly lost around 0.3s to the field post-Spain. That too helped create the gap behind Red Bull for the upgraded McLaren to thrust itself into.

So it begs the question of how well might McLaren’s promising trajectory be maintained into ’24.

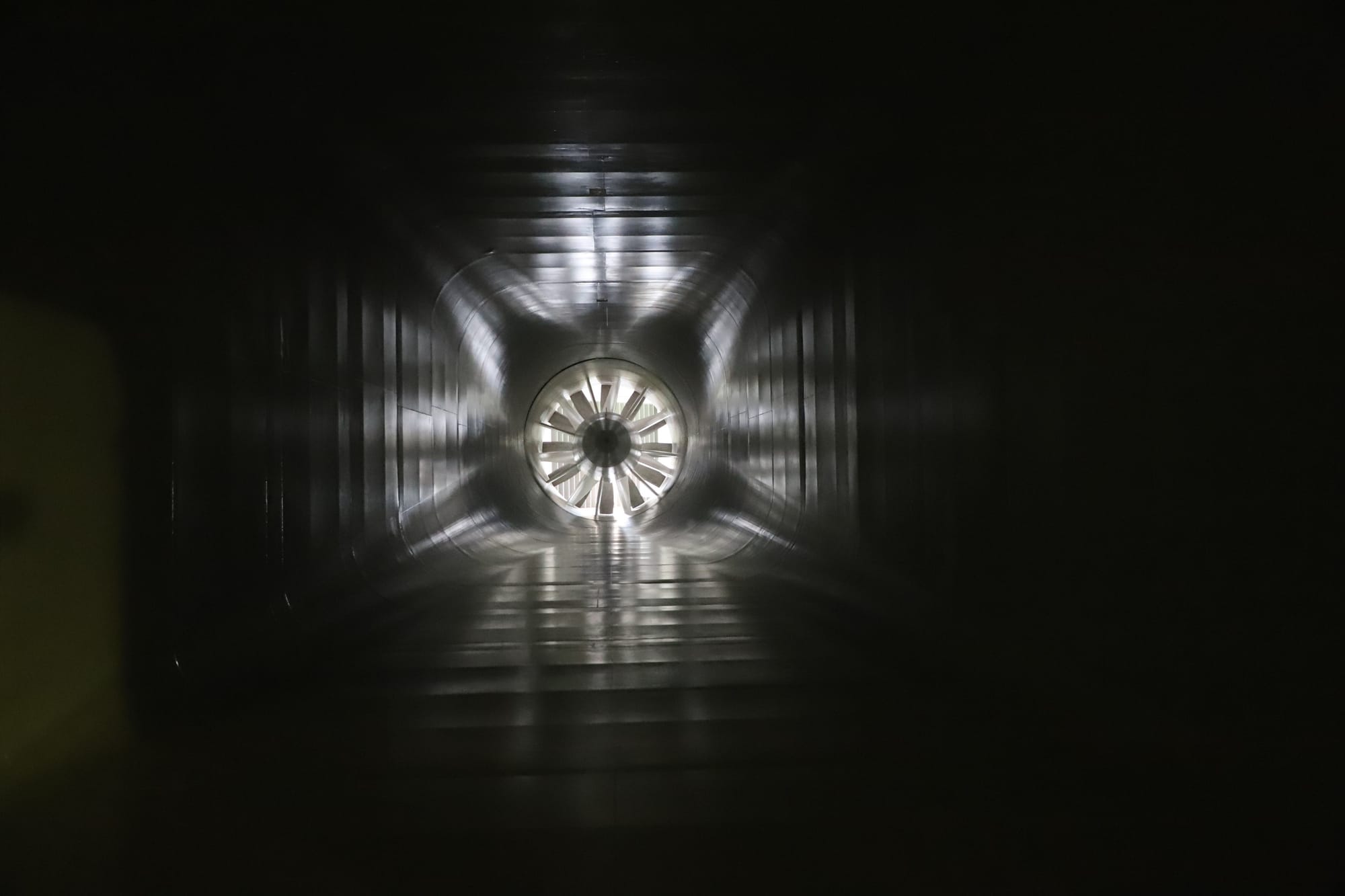

Previously, much was being made of how McLaren was stymied by the limitations of the Toyota wind tunnel in Cologne, now that it was no longer cutting-edge technology – and that real progress might have to wait until McLaren’s own in-house tunnel was up and running.

Which it now is.

Stella, while excited about the new tunnel, doesn’t see that as the big differentiator.

“If you don’t get the right concept to start with you are almost independent of the tunnel,” he says. “You can test there as much as you want. But it’s only when you get the foundations [of the car] right that the accuracy of the development tools such as the tunnel starts to give you some premiums.

"But these are the incremental gains. The major changes we were able to make from launch to Austria and Singapore was more to do with things you almost didn’t need a wind tunnel for.

"The tunnel doesn’t tell you what to do. They are as good as the quality of things you put in. You have to ask it the right questions.”

Stella’s vision extends beyond the simulation tools – and it’s this which is probably going to determine the sustainability of McLaren’s form. Because changing the car mid-season was about much more than just the hardware changes.

“To achieve what we did, I needed to work on the leadership model, to create the capacity in the leadership to be able to carry out the amount of work required. When I see opportunities I don’t want to wait and I saw there was an opportunity in the team and I can’t think, ‘Ok I’ll leave it until ’24.’ I can’t sleep.

"This led us to understand we needed to overhaul the functional model of the team, of how you identify the functions, how you lead them, how they should work with one another.

"This gave rise not only to the changes which happened early on but are still ongoing. There are a lot of things happening in the ground which are instrumental in this single vision.”