Up Next

The ban on teams developing the main areas of their 2026 Formula 1 cars until the start of 2025 has been enshrined in the regulations through further windtunnel and CFD restrictions.

After the F1 Commission agreed that “no work may be carried out on the development of a car” for 2026 before January 1, 2025, the FIA’s World Motor Sport Council has ratified rule changes to police that.

As expected, this is done by specifying limitations to restricted windtunnel testing and CFD simulations - essentially the same restriction invoked for the current generation of cars, when the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted the plan for new rules in 2021 and efforts were made to manage costs for the 12-month delay to the introduction of the new rules to 2022.

From December 1 of this year until January 1 2025, the only windtunnel work permitted is using a scale model that “substantially complied with the 2023, 2024 or 2025 technical regulations”.

Dyno testing aimed to develop brake system components “with minimal air ducting” can be carried out, as long as that does not test “or in any way provide incidental data or knowledge on” the performance or endurances of bodywork.

It is a similar story in terms of preventing CFD simulations, with the same December 1 2023 to January 1 2025 timeframe only permitting CFD work using geometries that “substantially comply with the 2021-25 technical regulations”.

Similarly, the “sole purpose of the development of the brake system components and associated test rigs” is the only exception.

HAD WORK ALREADY STARTED?

As the ban came into effect from December 1 this year, any work that may have been done before then is acceptable, although if any has been conducted at all it will be extremely preliminary given there are no defined chassis rules yet.

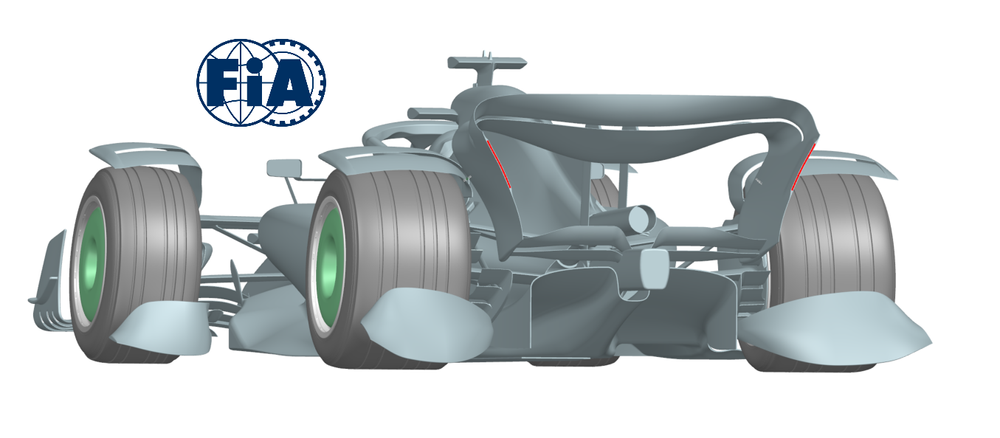

So far all that is known publicly is that the cars are set to be shorter and lighter, with reworked aerodynamics, less downforce and less drag - and an attempt to improve wake characteristics once again, although some would prefer a greater focus on how cars can better produce downforce in ‘dirty air’ rather than try to control the wake itself.

The lack of a set of published technical regulations would not necessarily stop teams working on their cars either now or next year without the ban in place, though.

There could be draft versions in circulation in private, which is why the regulations make a point of outlawing more than just working on cars that are defined by published technical regulations.

The rules forbid “using car geometry partially or wholly compliant with and/or substantially derived from drafts and/or published versions of the 2026 F1 Technical Regulations or FIA proposed 2026 bodywork geometries and concepts” for either windtunnel or CFD testing.

Team working groups will already be set up and looking ahead to 2026, though, and these may continue as long as nothing makes it to the windtunnel or CFD phase.

Although this does not go as far as what Lewis Hamilton suggested earlier this year - not allowing teams to develop next year’s car until a certain point in the season preceding it - it is a sensible measure that means teams can only commit meaningful development resource to their 2026 cars for the 12 months prior to that year.

It means that all windtunnel and CFD work, in terms of cost and the time spent, will be entirely factored into teams’ 2025 budget cap and aerodynamic testing restriction allowances, and stop anyone attempting to get a headstart by sacrificing their 2024 seasons and/or their 2025 cars.

This could have been tempting - it is similar to what the likes of Haas and Sauber did ahead of 2022 after all - as early development ahead of a new set of regulations can buy a team a big advantage.

That is still going to be a factor though, and these restrictions place all the emphasis on deciding when to switch off development in 2025 to put full focus of time and money onto the 2026 car.

WHAT ABOUT ENGINE DEVELOPMENT?

Given the scale of the technical undertaking, the restrictions for power unit development are not as severe - and nothing substantial has changed from what has been laid out for some time now.

Although the V6 turbo-hybrid engines are being retained following a lengthy run for the first generation versions that were introduced in 2014, there are significant changes coming.

The MGU-H has been dropped for 2026 but the electrical power output is increasing significantly because of a massively uprated MGU-K and battery, which will put the split between internal combustion engine and electrical power close to 50/50.

The six registered power unit manufacturers - Red Bull Powertrains, Mercedes, Ferrari, Honda, Alpine (Renault) and Audi - have been permitted to work on the 2026 engines without obstruction, and obviously no ban like that of the aerodynamic work is going to be implemented.

But there are limitations on how they are developed that cover the equipment that can be used, how much time can be spent using them, and for the first time how much money can be spent.

Power unit test benches are limited to three single-cylinder dynos, three power unit dynos, one powertrain dyno and one full car dyno, as well as two energy recovery system test benches and one energy store (battery) test bench.

Operation hours - defined as when engine speed exceeds 7500rpm on the dyno - are limited to 5400 cumulatively across 2023, 2024 and 2025 with a limit of 2160 hours for each individual year in that period.

Existing or prospective fuel and oil suppliers are not allowed to operate a test bench for the purposes of 2026 engine development with the exception of one single-cylinder dyno exclusively for the development of the fuel and/or oil.

There are also financial restrictions in place ahead of 2026.

In 2023, 2024 and 2025, engine manufacturers may spend $95million per full year reporting period - although new power unit manufacturers (Audi and Red Bull Powertrains) get $10m in 2023 and 2024, and $5m extra in 2025.