Up Next

Ferrari’s United States Grand Prix performance will be a key indicator on whether it’s on the right track technically, even though it doesn’t have any significant upgrades to introduce.

While Ferrari is working on a floor upgrade that could be trialled before the end of the season with an eye on 2025, this will not appear for the United States Grand Prix sprint weekend.

That’s despite team principal Fred Vasseur raising expectations of an improvement after the Singapore Grand Prix when he said the team would try its best to have a "small upgrade” for the next race.

But that was a month ago, and now he’s framing Austin as a test of the upgrades it has already introduced before - with any changes here expected to be minor details to help optimise the package.

“Since Singapore, we have been working flat out and the high-speed turns at this track will provide a useful test for the upgrades we introduced at previous races,” said Vasseur.

“As is always the case at a sprint weekend, the work carried out at the factory prior to the event takes on greater importance, with only one hour of free practice before immediately going into the competitive part of the event.”

You could argue that’s using the sprint as an excuse for a lack of progress, but it’s pragmatic given the lack of free practice running - even with this year’s change of rules that lifts parc ferme between the sprint race and qualifying proper.

However, there’s a more powerful argument for this being a rational strategy for Ferrari that’s rooted in the development progress it has made.

A key misstep in Ferrari’s season was the major floor upgrade introduced at June’s Spanish Grand Prix.

This created problems with bouncing and, with Ferrari having reverted to the old-specification for the British Grand Prix in early July, a small modification to mitigate the problem appeared at the Hungarian Grand Prix later that month.

A new floor was then introduced for the Italian Grand Prix at Monza, the second race after the August break, that appeared to work well.

After Ferrari won at Monza, it also performed well in Azerbaijan where Charles Leclerc took pole position and finished second. But as Carlos Sainz warned that weekend, there was always the risk this run of form was an illusion.

“It could give us a good run,” said Sainz of the sequence of races in Italy, Azerbaijan and Monza. “But at the same time, maybe a fake one because then you go back to Austin and the car is like it was in Zandvoort and you’re lacking.”

That’s what makes this weekend a key test, not only of the new floor that appeared at Monza, but also of the new front wing that was introduced in Singapore a month ago.

The question is whether this recent run of form for Ferrari was purely down to the track characteristics suiting the car, or if the car upgrades played a big part.

Answers to that question have been equivocal from the team itself, perhaps because it doesn’t know for certain if even simulations at the factory indicate that it should be the case.

Ferrari’s main weakness this season has been on high-downforce tracks, particularly those with longer corners – especially faster ones. However, it has also struggled when there has been a wide range of corner speeds.

That makes Austin a good test of its car as although it’s a track with plenty of faster turns, there’s also some slower content.

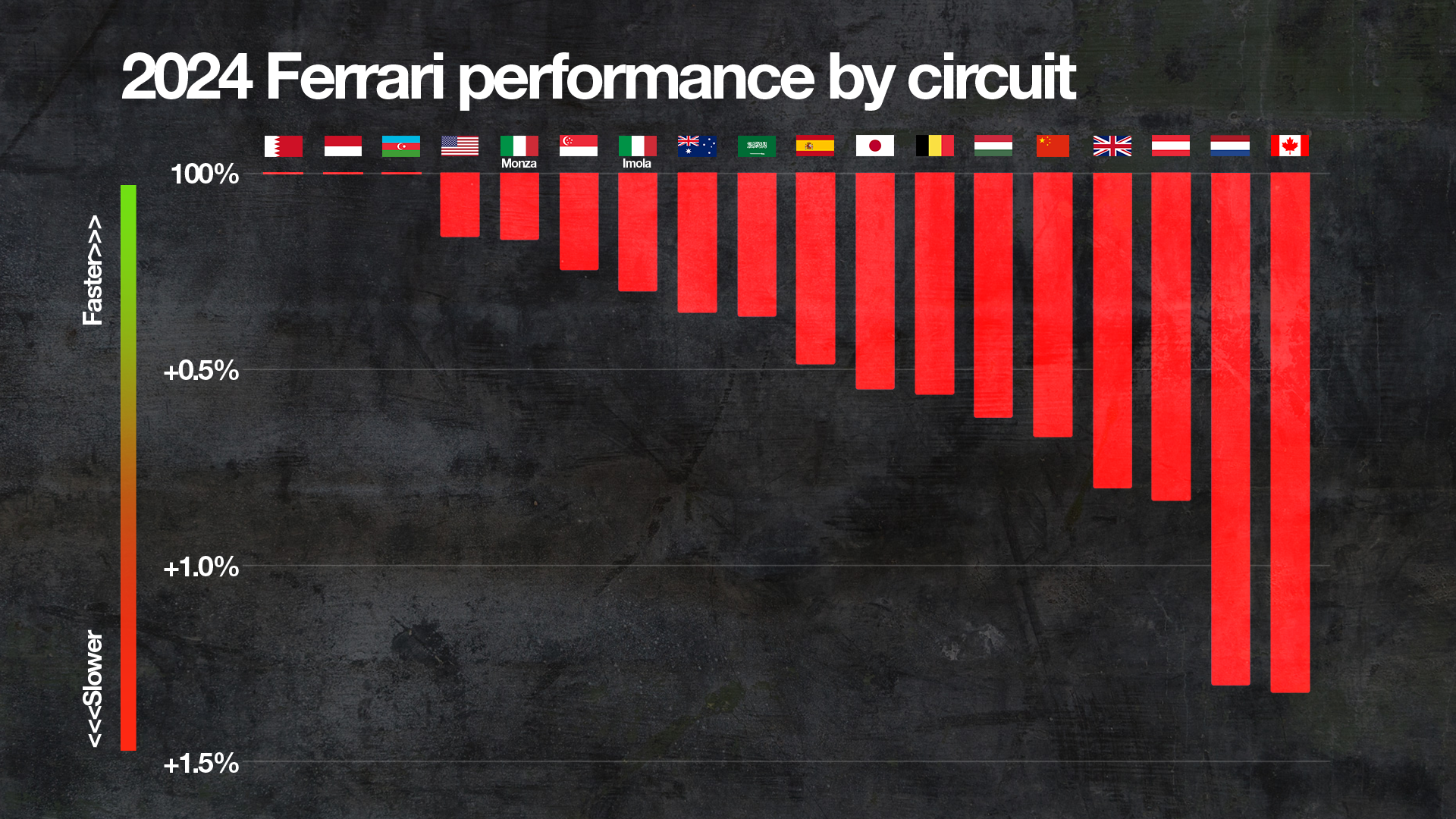

There’s a very interesting pattern in Ferrari’s single-lap pace across the season. The Race’s supertimes metric, which utilises each car’s fastest single lap of a race weekend expressed as a percentage, shows a clear pattern when you arrange the tracks visited so far this season in pace order.

There are three tracks where Ferrari has been outright fastest. Two of those are no surprise - Monaco and Baku. The other is Bahrain, which is something of an anomaly given that was based on a Q2 lap by Leclerc that he couldn’t repeat when it mattered in Q3.

Bahrain is not as conventional a circuit as it perhaps looks, and Ferrari’s gentleness on the tyres there, and the punch its power unit packs off slower corners thanks to having a smaller and therefore more responsive turbo than its rivals, meant it performed well.

Also in the top half of Ferrari’s tracks so far this season are Miami, Monza, Australia and Saudi Arabia. Clustered in the bottom half are more conventional tracks, including circuits like Austria - the track that features the highest percentage of traction-limited cornering time on the calendar - and Zandvoort.

At the bottom is another anomaly, Canada.

The Circuit Gilles Villeneuve is a curious track, one that generally gets considered among the street tracks, but it was a weekend on which everything that could go wrong did go wrong for Ferrari. Both cars were eliminated in Q2 thanks to misjudging the starting tyre pressures - and Leclerc was down on power in the race.

So why has the Ferrari worked so well on street tracks and not so well elsewhere?

Well, for starters, the aforementioned smaller, more responsive turbo always guarantees good power delivery off slow corners.

The Ferrari is also an agile car that rides kerbs well and that can be very effective in short, sharp, slow corners.

At a track like Baku, for example, that’s helped by the low wing levels that makes the rear end fractionally unstable and therefore helps the front end turn in well. It’s also confidence-inspiring under braking, for Leclerc in particular.

Much of this will be down to the mechanical platform of the car and those characteristics have been present for several years.

So why doesn’t that translate to regular tracks?

Using its most recent bad track - Zandvoort - as an example, Leclerc described the Ferrari as “just understeery, can’t rotate the car”.

As Ferrari senior engineer Jock Clear admits, Ferrari has been backed into a corner at higher-downforce tracks thanks to that lack of front-end.

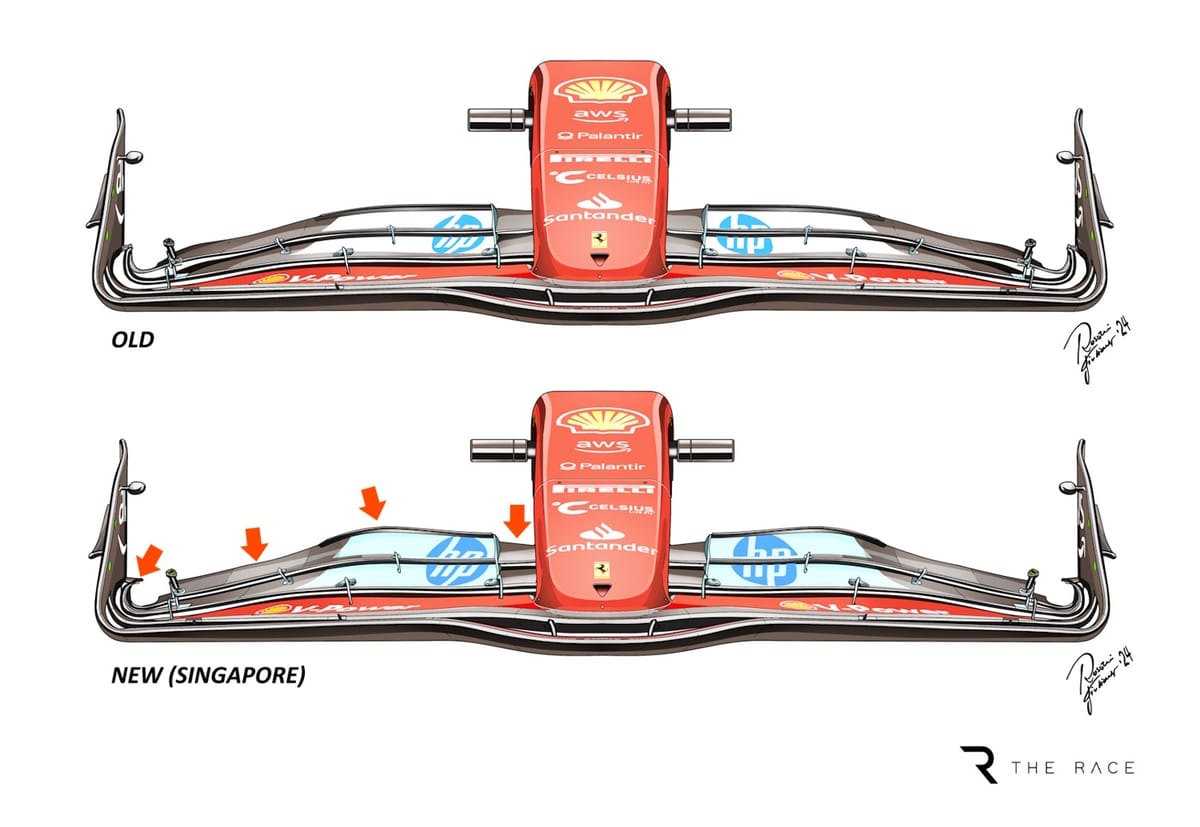

“Basically, it’s just moving the energy a little bit inboard,” said Clear of the new front wing in Singapore.

“If you look at it closely, you’ll see that the inboard is a bit more aggressive and the outboard is a bit less aggressive. So you’ve moved that dynamic a bit. It allows us to crank on a bit more [front wing].

“We’ve been a little bit backed into a corner at some of the high-downforce circuits because we’re running out of front power, so it’s just a bit more powerful at the top end.

"Slightly more efficient, marginally, but it’s the fact that it’s a bit more powerful at the top end, which gives us a bit more scope.”

The front-end weakness at lower speeds is a generic trait of these ground-effect F1 cars, one that Ferrari hasn’t mitigated as well as others, partly because it’s not as advanced with flexible wing technology as McLaren and Mercedes are.

The Ferrari has also, in contrast to the previous two years, tended to look after its tyres well in the race but struggled to warm them up thanks to being almost too gentle on the Pirellis.

That’s the case regardless of track configuration, and makes the SF-24 a stronger race car than qualifier.

The Austin performance will also be an indicator of whether Ferrari has solved the underlying problems with its tools that contributed to it going the wrong way in the first place.

“After Spain, we didn’t feel like we’d lost our way but there was some anomaly between what was happening in the [wind]tunnel and what we were seeing on track and we had to get on top of that,” said Clear.

“That is the process. When you see an anomaly you have to get on top of it, try and understand it, and get back on track.

"What we’ve seen since is that we understood it, we got back on track, we just have to be eyes-wide-open on what the next anomaly will be, because there will be another one.

“So it’s not that sometimes the development works [and] sometimes don’t work.

"You are testing something new every week and tunnels, with the technology that we have, they don’t have the ability to model everything perfectly, and maybe 20, 30 years in the future, we’ll be much better-equipped, but at the moment there are differences between what you see in the tunnel and what you see on track.”

Ferrari has made tweaks to its windtunnel to produce more precise data given how sensitive these cars are in yaw.

It’s understood this has led to improvements with the rolling road system, which is a key technical battleground for the current cars given how close it runs to the ground. Austin will be the first chance to test the products of all these improvements at a conventional track.

And this all matters not just because Ferrari wants to rekindle the dying embers of its constructors’ championship push and win more races, but because of the implications for next year.

If it has understood the root cause of its car problems, including those of porpoising and the limitations that make it a car better suited to outlier tracks than more conventional circuits, then that is good news for its hopes for 2025 and beyond.

If not, then that could mean Ferrari continues to have a similar performance pattern for a good while yet. And while that means there will be more victories, the danger is that a championship win would likely remain out of reach.