Up Next

Formula 1's ongoing row over flexible wings took a fresh twist over the Azerbaijan Grand Prix weekend, as attention switched from controversy over front wing flexibility to an apparent trick McLaren has come up with on its rear wing.

In Baku, the rear-facing onboard camera from Oscar Piastri's race-winning McLaren appeared to show the top element of the rear wing deflecting at high speed.

This wasn't quite as obvious as an entire rear wing structure flexing to create lower drag, which is something the FIA first began cracking down on in the middle of 2021, but it looked like something designed to achieve a similar effect to a lower order of magnitude.

It looked like just the top element of Piastri's wing - the part that opens when the DRS is engaged - was able to bend or twist slightly at its outer edges, therefore increasing the slot gap between the two main wing elements when DRS was not in use.

This would reduce drag, giving any car that was able to use it a small straightline speed boost that could be very beneficial on a circuit such as Baku, where such long straights mean all teams need to compromise downforce levels to reduce drag.

It would also be especially beneficial to a driver leading the race, who is not able to use DRS himself, trying to fend off a faster Ferrari for dozens of laps along one of the longest straights on the F1 calendar.

Charles Leclerc was surprised by the McLaren's end-of-straight speed as he unsuccessfully tried to repass Piastri in that race.

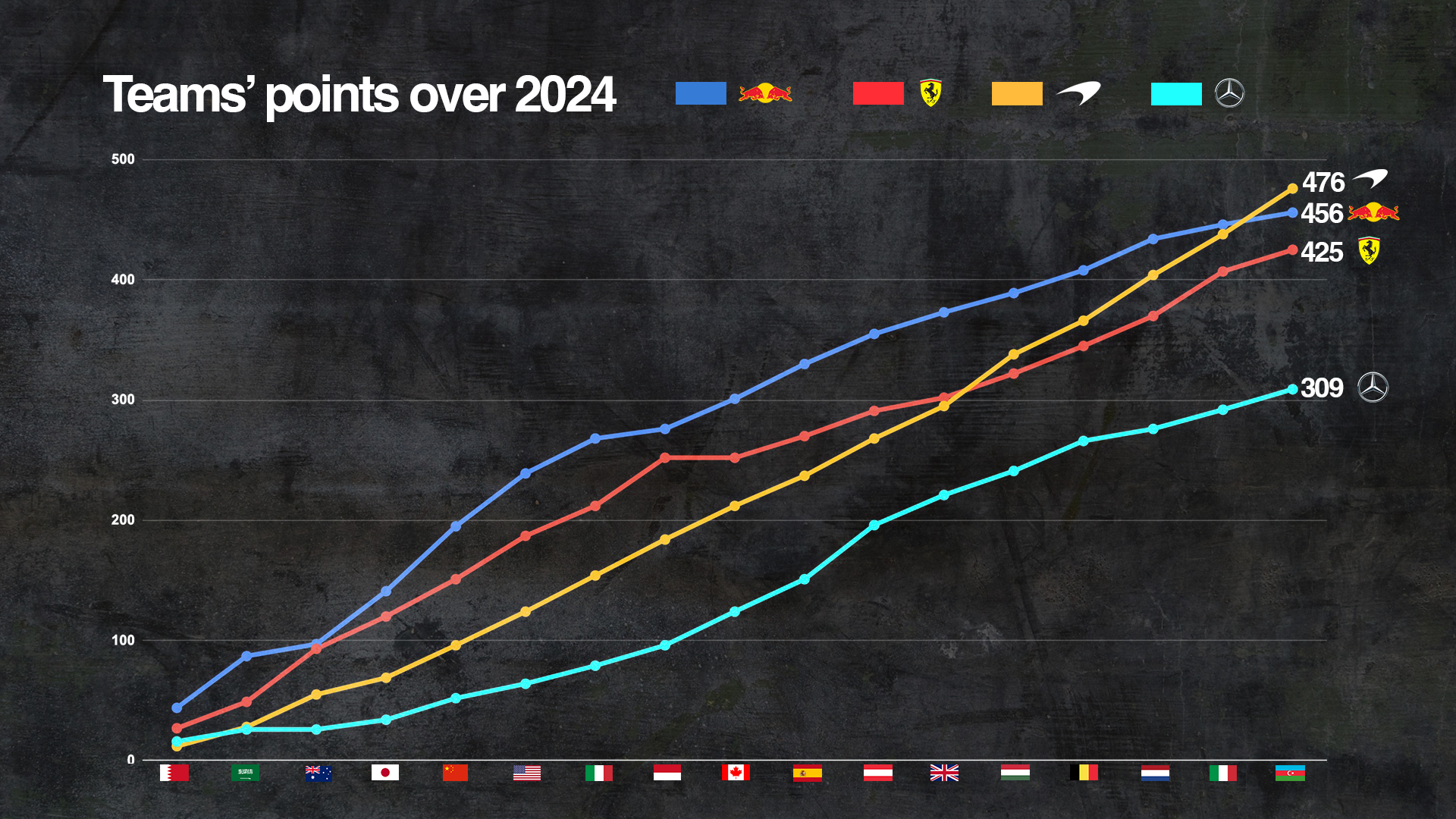

Both were using their Spa specification rear wings - which were significantly smaller than the one used by Red Bull, and a little bigger than the one used by Mercedes - so Ferrari and McLaren were quite similar to each other in their chosen downforce levels.

Where the McLaren may have had the edge was in the behaviour of that rear wing when not in DRS mode.

How it works

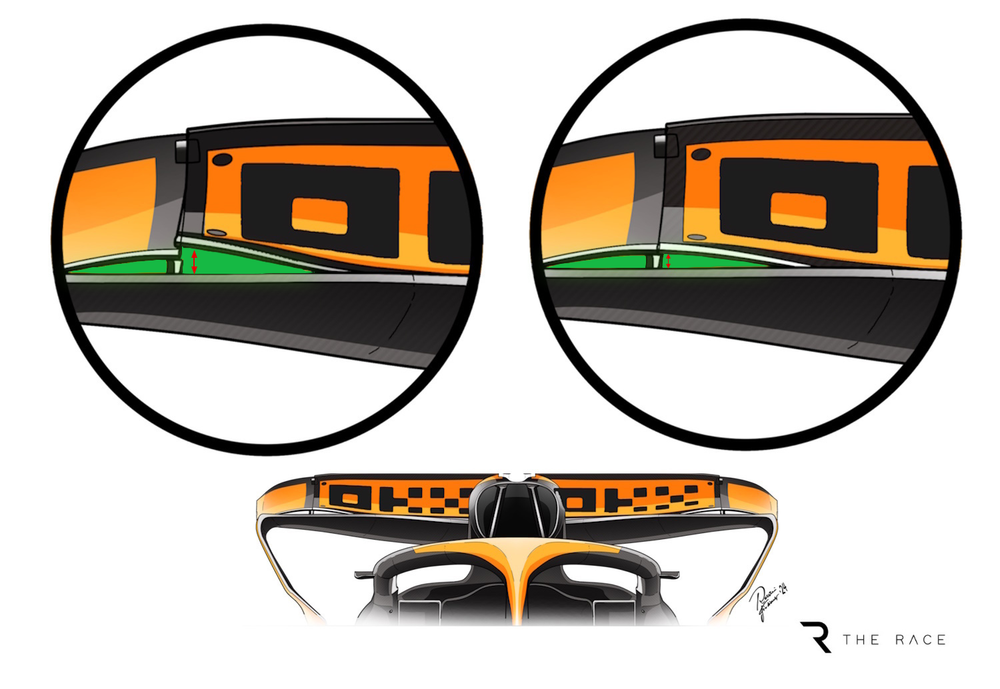

There is TV footage of the McLaren's rear wing at speed, showing the gap between the main plane's trailing edge and the leading edge of the flap.

At high speed we can see the flap leading edge deforming a little, increasing the gap between it and the main plane, which would reduce drag.

It's effectively creating a sort of mini-DRS effect - but without actually using the DRS.

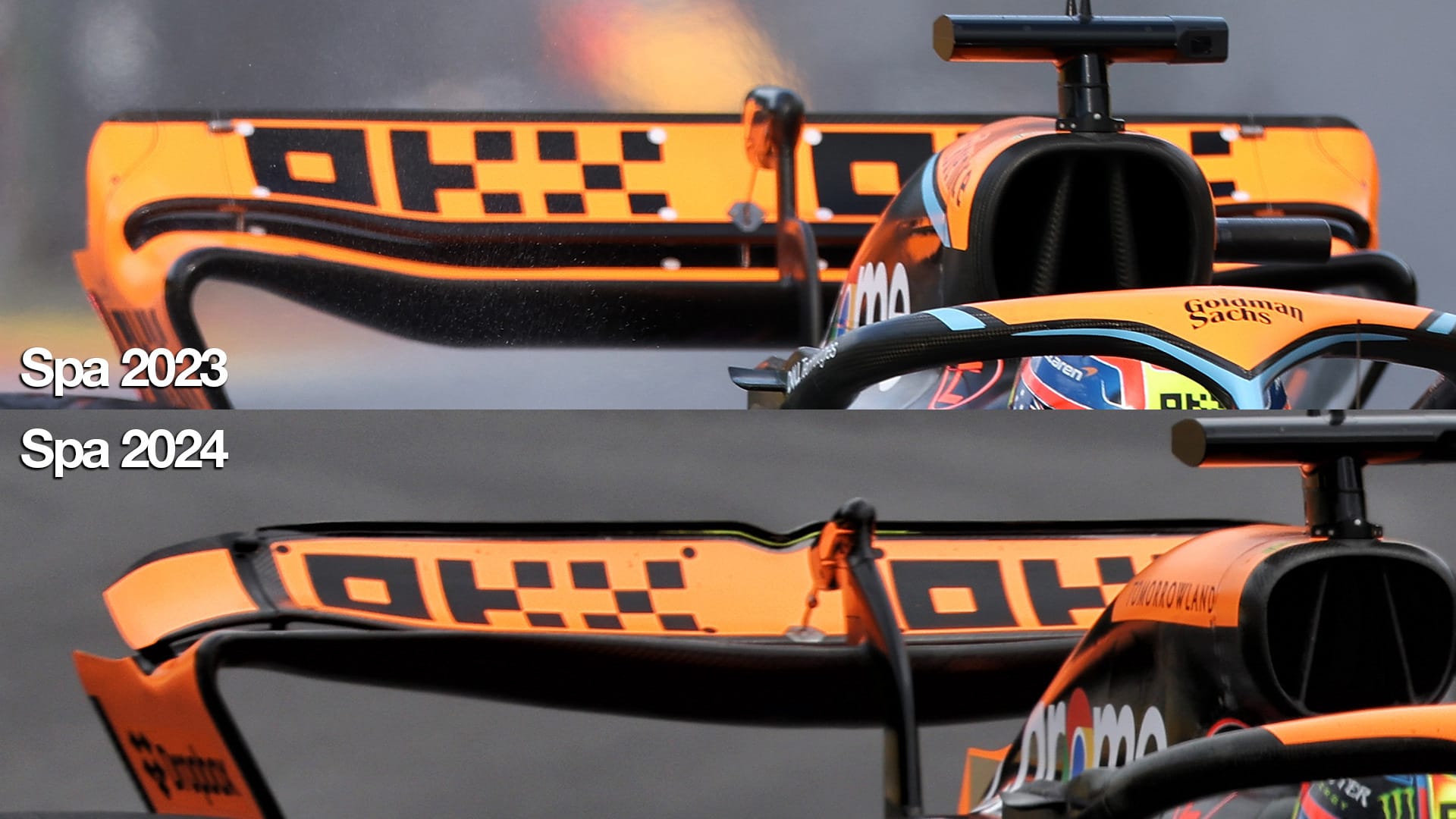

A lack of aerodynamic efficiency on its rear wing is a specific weakness McLaren identified during the middle phase of last season.

At Spa in 2023, Lando Norris said McLaren was losing close to a second per lap because of the need to run a rear wing that was too large.

McLaren did have a smaller one available, but team boss Andrea Stella admitted it was so inefficient that running it would have made the overall performance of the car even worse.

But having managed to find loads more pure performance from that incredible rate of development that kickstarted in 2023, McLaren has now been able to switch focus to improving drag at specific downforce levels where that becomes a real sensitivity for the car's overall performance.

That means circuits like Spa, Monza and Baku, where you have to trade off the level of downforce you want for the corners against the need for greater speed on the straights.

Fast forward to Spa 2024 and McLaren introduced what it called a new family of rear wings, "upgraded around some more modern concepts", according to Stella.

So it's not too much of stretch to intuit that McLaren has applied some of the clever aero elasticity it has utilised to such great effect on its front wings to create an efficiency gain on its rear wings too.

How is it legal?

Such a visual example of F1 teams' never-ending battle to create aerodynamic elasticity - which still passes the FIA's static tests - understandably created alarm among those who believe something like this should be illegal.

But McLaren's car remains on the right side of the law. That could change of course, but for now this is not an area under the FIA's active interrogation.

The same, of course, cannot be said for the front wings - which the FIA has actively investigated and monitored with cameras since before the summer break.

But again, so far the FIA has found nothing untoward.

Being able to reduce the drag penalty you pay for running more downforce is a target all teams are constantly chasing and F1 is always about trying to exist in the grey areas of the regulations.

No aerodynamic surface can be completely rigid at all times, as they would snap under the loads created at speed, so therein lies some inherent wiggle room that all teams could potentially exploit.

The rear wing flaps will be subject to load testing, just as the front wings are. But the FIA isn't able, with its current equipment, to replicate real loads in those static tests.

So this creates a fundamental playground for F1 teams to operate in: build aerodynamic parts with enough stationary rigidity to pass the static load tests, which then deflect usefully at speeds at which their rigidity is - for now - impossible to test.

It's logical the front wings have taken more of the FIA's focus recently, because that's an area where you can really gain a compound benefit in this ground effect era of F1.

Trying to achieve a sensible balance compromise between high and low speeds has become much more difficult as F1 has moved into ground effect.

Elastic aerodynamics appears to be the most effective way of taking the front wing out of ground effect at high speed - when you want rear stability and reduced front grip - while then still being able to run the level of wing angle you ideally want at lower speeds, when heaps of front grip and a positive turn-in is the most desirable handling characteristic.

So the amount of laptime you could potentially gain from this is also a function of how much easier the car is to set-up and drive, rather than a pure downforce versus drag numbers game.

The rear wing deflection seen on Piastri's car in Baku is maybe worth a tenth of a second on that long straight - and only in the race too, because in qualifying every car has use of DRS and at the speed the wing is 'backing off' DRS would already be active.

There would still be a gain at more conventional circuits too - but probably more like hundredths of a second.

However, in a race situation like the one Piastri found himself in at Baku, even a tiny gain from this might make the crucial difference that could prevent a chasing car getting close enough to make a pass for the lead.

Is a clampdown coming?

Although McLaren is doing a great job of exploiting permissible levels of elastic aerodynamics with its front wing right now, much to the annoyance of championship rival Red Bull, nothing in F1 lasts forever.

Twelve months ago, ahead of the 2023 Singapore Grand Prix, the FIA introduced a new technical directive aimed at clamping down on wing elements that were designed to 'back off' at different rates along their length depending on the speed the car was travelling.

In issuing that technical directive, the FIA basically accepted aerodynamic components have to be allowed to deform at speed, but it wanted to see that 'backing off' be uniform across the length of each component.

A glance at the current technical regulations on rear wing deflection suggests the wording is mostly focused on how the trailing edge of the rear wing moves back at speed, rather than the bottom edge of it lifting up as appears to be the case on the McLaren.

It could also be that the FIA's current deflection test parameters don't quite cover that area McLaren is exploiting - so it could be that the FIA actually needs to invent or modify its testing regime in order to check this area in the first instance.

It also seems that the FIA has recently been more preoccupied with regulating rear wing deflection when DRS is active, perhaps because of how potent Red Bull's DRS efficiency was in the early period under this set of rules, while McLaren's latest trick only works without the use of DRS.

The level of complication and technology involved in this area would explain why the FIA is seeking to make a more general clampdown on aero elasticity for 2025, rather than immediately targeting some of the things we're seeing in F1 now.

Sometimes the regulator simply has to accept when F1 teams cleverly exploit loopholes in the existing regulations - as Mercedes did with its one-season wonder dual-axis steering system in 2020. You basically take it on the chin and then write it out of the rules at the earliest available opportunity.

That's obviously much more difficult with an area like elastic aerodynamics, where there fundamentally has to be a certain level of permitted flexibility - something the FIA itself accepts.

But given this current battle has been raging between the FIA and F1 teams since the middle of 2021 we can probably expect something to be done to peg McLaren back by the time the 2025 season gets under way.