Formula 1’s all-new engine regulations coming for 2026 triggered their fair share of horror stories as teams and drivers first began to explore the new rules.

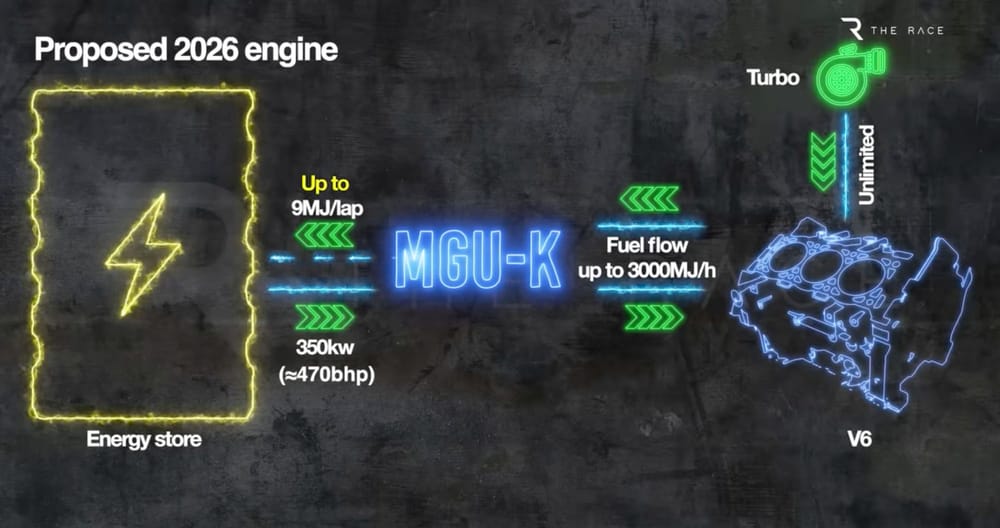

There were concerns about the shift towards a 50/50 power split of the internal combustion engine and the battery leaving cars starved of energy - which prompted fears of races turning into economy drives, of teams being so desperate to harvest electrical power that cars would be revving flat-out under braking, and of huge speed drop-offs on the straights that could even require drivers to change down gears.

This was something that world champion Max Verstappen famously highlighted after trying out an early iteration of the 2026 car on the simulator.

“If you go flat-out on the straight at Monza, and I don't know what it is, like 400m or 500m before the end of the straight, you have to downshift flat-out because that's faster,” he said.

“I think that's not the way forward. But of course, probably that's one of the worst tracks [for it].”

With F1 now just 12 months out from the power units running on track for the first time, however, a different picture of what we can expect has emerged now that manufacturers and teams are working on the engines in real life on the dynos.

The Race has spoken to senior figures to get a better picture of where things are at with the 2026 engines, in an attempt to separate the myths and the scare stories from the realities.

A false picture

To understand why current predictions for the new engines are in contrast to the fears voiced a while ago, it is important to get to the bottom of the catalyst for those early worries.

When the first alarm bells started ringing over the 2026 engines, some viewed it as scaremongering from teams who were perhaps worried about the performance of their own product.

However, that theory did not really stack up as some of the themes - such as cars running out of energy on the straights - seemed to be pretty universal among a host of manufacturers.

What is important to understand about those findings though was that they came from a false picture - because the cars being run on the simulator to deliver that outcome were nothing like what we are going to get in the real world.

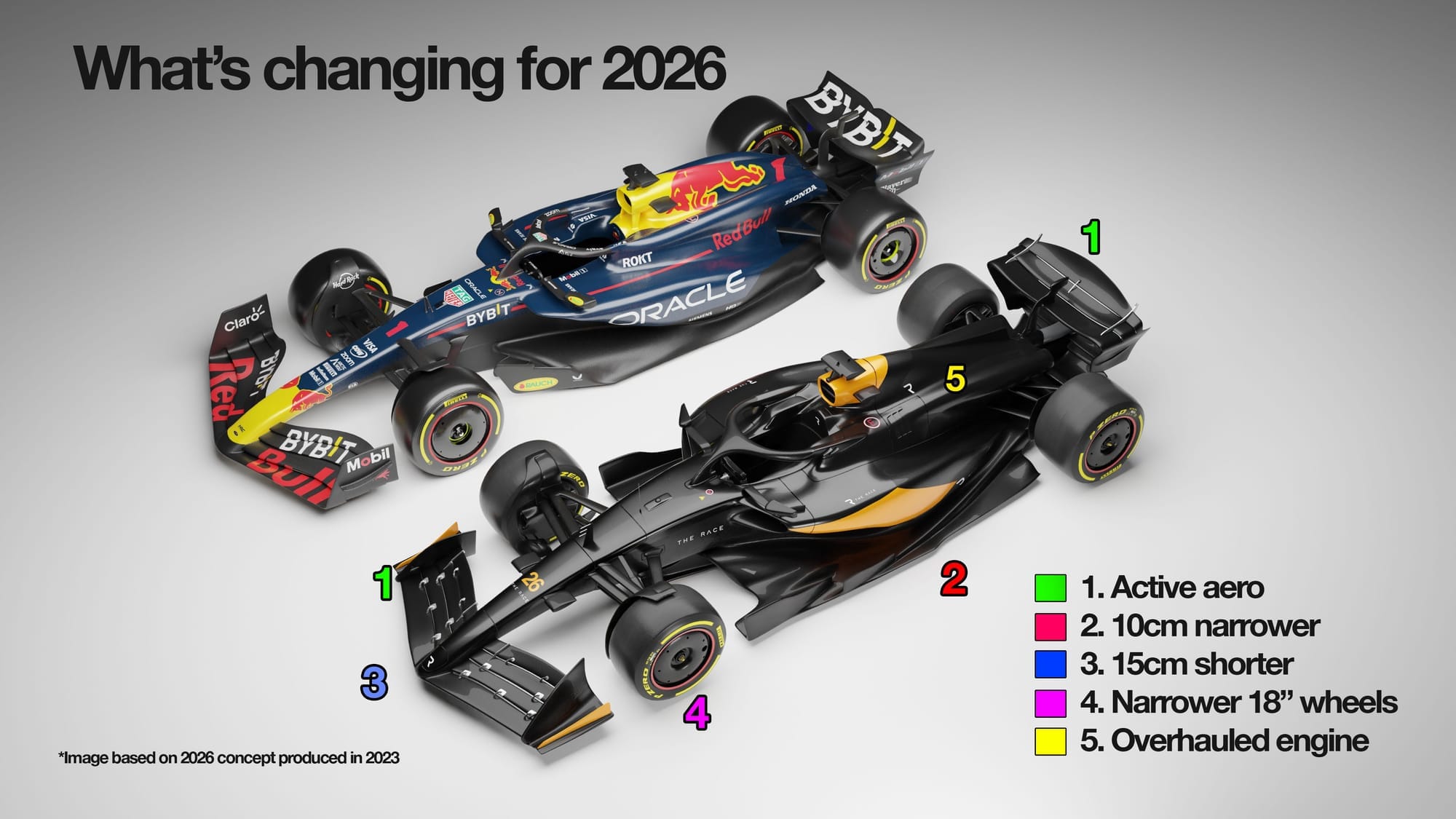

Early simulations of the 2026 power units that were being run in 2022-23 were based on the drag and downforce levels of contemporary machinery - which are way higher than what the new cars are going to be like.

It is only as teams have begun to evaluate a more accurate picture of what is coming - which includes active aero for less drag on the straights and more downforce in the corners - that the real picture emerged.

And it has become pretty obvious that how teams choose to pitch the downforce/drag of the cars makes the difference between delivering some alarming findings in the simulator and actually looking in pretty decent shape.

The consensus seems to be that things are heading in the right direction - even if there are still some challenges to overcome and potentially some fine-tuning of the regulations to be done.

That end-of-straight drop-off

Most 'doomsday scenarios' put forward about the 2026 engines typically involved Monza and drivers running out of battery, then needing to be changing down gears on the straight to ensure the engine revs did not die totally.

While there is no denying that tracks like Monza - which have long straights and minimal opportunities for energy recovery - will be a big challenge for the 2026 power units, the picture emerging for most of the calendar is quite upbeat.

The way that drag has been reduced for the 2026 cars means that the energy required to propel the cars down the straights has been reduced - so, on the current trajectory, the batteries will be lit up further than originally thought.

Furthermore, two additional demands have been put in the regulations to ensure that drivers are not suddenly left with zero power halfway down the straights.

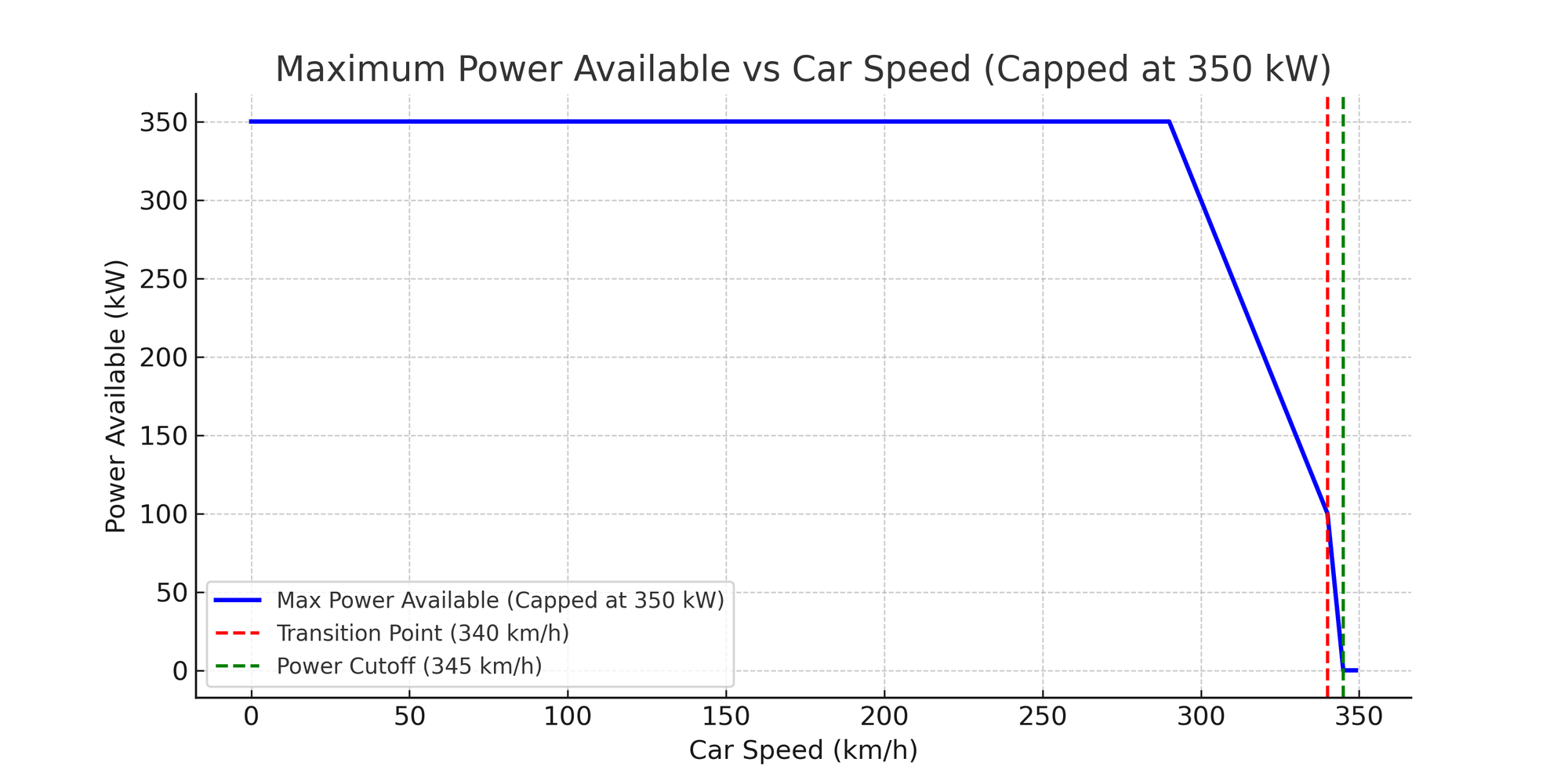

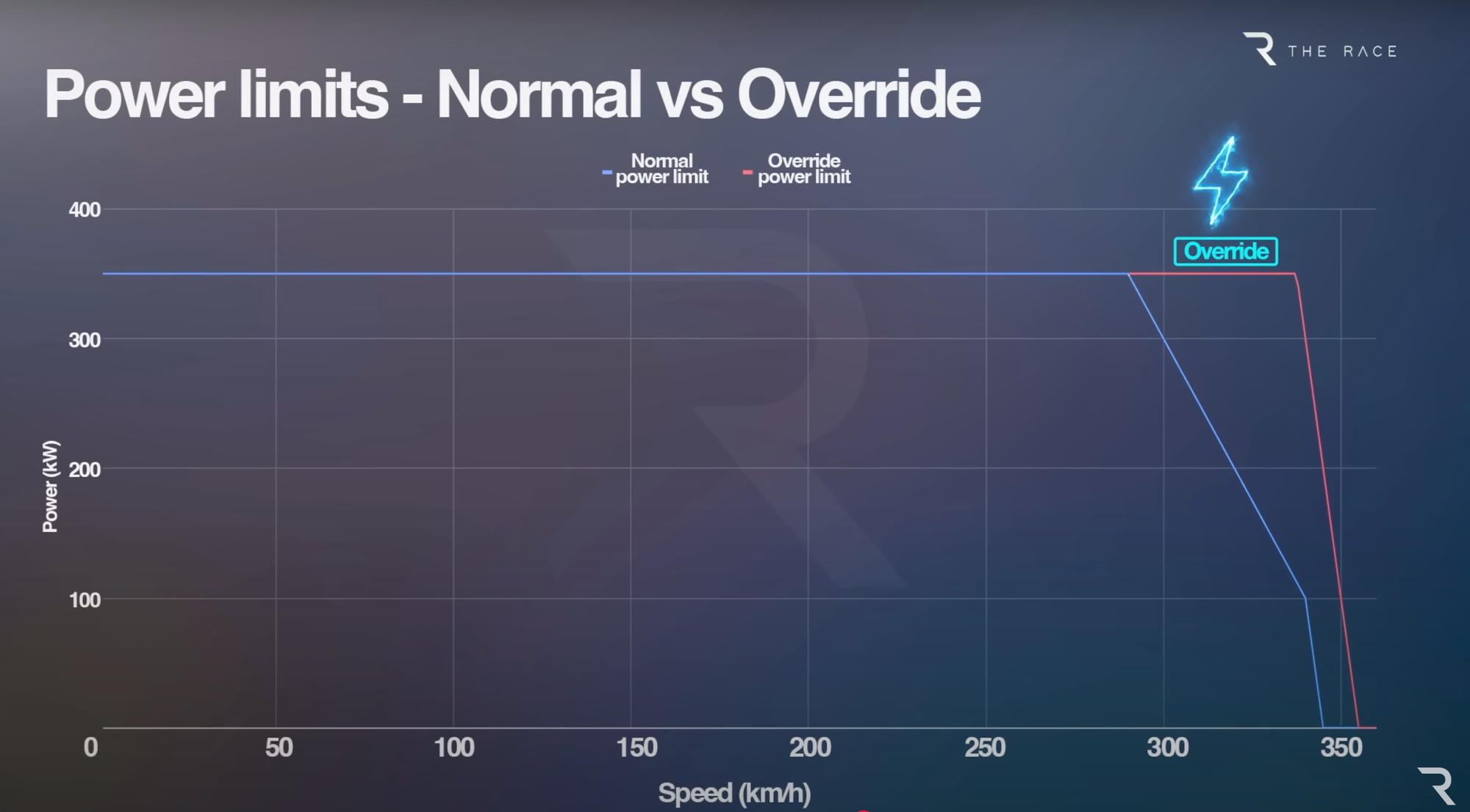

The first relates to car speed and demands that once the cars are up to a certain velocity, then the limit of electrical energy that can be used starts dropping away from the peak 350kW allowed with the 2026 power units.

As the graph shows, this starts reducing as cars approach 300km/h, then tapers off more aggressively from 340km/h before it hits zero at about 345km/h.

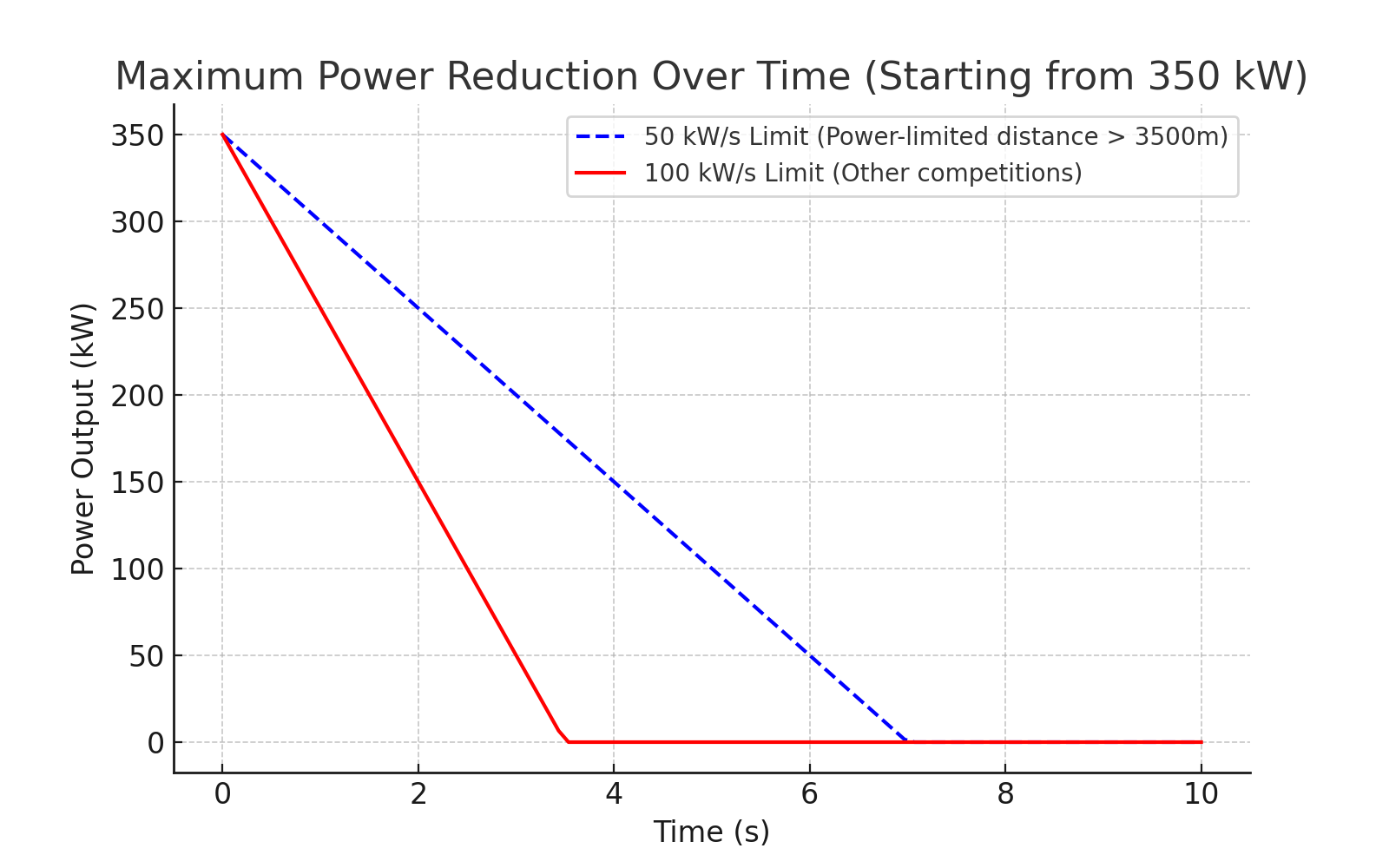

Perhaps of more importance, however, to how things ultimately shake out is an article in the technical regulations that limits the rate at which power can be reduced - so there is no cliff edge potential.

This is known as the ‘turn down ramp rate’ and effectively prevents teams from burning all the power quickly to arrive at a point where drivers go from having maximum power to none in an instant.

There are two ramp rates laid down: one for tracks where power will be very limited, and then a different metric for everywhere else.

At those tracks where the FIA determines that the power-limited distance exceeds 3500m, the power can be reduced at no greater rate than 50kW in any one-second period.

For other venues, the rate of reduction is capped at 100kW in any one-second period.

You can see in the above graph how long the power reduction runs for.

At Monza, which will fall into the power-limited track category, it will take seven seconds for the MGU-K to go from 350kW to 0kW.

The start/finish straight there is approximately 15 seconds long. So if there was in theory enough energy to run for half that straight at max power (say, 7.5 seconds) without any restrictions, with the ramp-down it would mean around four seconds at 350kW, followed by seven seconds of ramp-down.

This means 11 seconds of energy in total - which is now three quarters of the straight. That scenario is very different to those early fears.

Combined together, these rules force teams to focus on efficiency of the battery power rather than efficiency of laptime.

This will prevent teams doing what they would have done without any restrictions - which is deploying the full 350kW at the start of the straight until it ran out all of a sudden, leading to some potentially troubling scenarios.

Extra harvesting in the corners

It does not take a genius to work out that, with F1’s 2026 engines having got rid of one electrical harvester (the MGU-H) at the same time as increasing the demands on the battery, the new power units will be more energy starved.

This means that teams will be chasing extra hard for ways to get as much power into the batteries as they can.

Last year, F1 design genius Adrian Newey said that people will have to get used to a different behaviour from engines - especially in cornering.

“It's certainly going to be a strange formula in as much as the engines will be working flat-chat as generators just about the whole time,” he said. “So, the prospect of the engine working hard in the middle of Loews hairpin [in Monaco] is going to take some getting used to.”

The suggestions of engines being revved high through corners seems weird, but is not actually that dissimilar to what we’ve had in the past - like in the exhaust-blown diffuser era when engines were still running off-throttle when turning.

The quest to maximise the harvesting of energy means that under braking and in corners teams will want to get the full benefits of the performance of the combustion engine even when the driver does not want it.

So as a driver enters a corner, rolls off the throttle and puts on the brakes, the speed of the engine will want to be kept as high as possible - so more energy can be harvested, even if it is not going to the wheels.

This could place a greater emphasis on drivers being asked to go much lower down the gears than they would ideally like - with the potential for the power unit to be revving a bit more than would be normal.

Early simulation data and dyno running does not indicate that this will sound abnormal though, and it is something that even takes place occasionally with the current power units.

Drivers may not like it, as it may seem unnatural, but if that’s the way to a faster laptime - because it gets you more energy in your battery and that gives you greater energy deployment somewhere else around the lap - then it will need to be done.

Another characteristic at play will be the likelihood of teams wanting to keep the turbo spinning through corners to avoid any lag coming out.

While ultimately there will be differences for the technicians in how engines behave in corners compared to what we have right now, to observers the change will not be obvious - and it may be quite spectacular to have some high-revving cornering.

One engineer said: “There won't be a disconnect between what you see and what you hear. From everything I've seen and heard on the dyno, it gears up normally and the audio cues are still very in line with what you expect. It’s just a bit noisier going around the corner.”

Even faster in Monaco?

One thing the switch to a 50/50 combustion engine/battery power split hasn't done is altered the overall power output.

The balance between ICE and electrical (850hp/160hp currently to 530/470hp in 2026) ends up delivering very similar overall power of around 1000hp.

Early indications point to the performance of the engines being every bit as good as now - and there is even the chance of acceleration being slightly better.

Electrical power delivery can be quite sharp, and that means the cars could be quite torquey - and even more so depending on how people have set up their turbos or are compensating for turbo lag.

There could also be some tracks that prove to be quite an eye-opener in terms of performance - especially Monaco, which has lots of braking and corners for energy recovery, and only short straights for deployment so running out of battery will not be a problem.

Overtakes could become tactical

F1 will be moving away from the reliance on the drag reduction system (DRS) to a new system that is known as 'Manual Override Mode'.

This is, in simple terms, a power boost button that allows drivers to fill in for any energy lost in the glide path regulations discussed before and provide the full 350kW of energy until around 340km/h, before it tapers and expires completely at 355km/h.

While this should deliver the same overtaking spectacle as DRS, one of the more enticing aspects will be how this element is used tactically.

Drivers are going to have to balance out burning up battery power for an overtake against the risk of then being left without any energy around the later stages of the lap.

There could be mistakes made in drivers blasting past rivals on one straight, only to find themselves a sitting duck a couple of corners later.

The sound factor

One of the early criticisms about the switch to turbo hybrids in 2014 was that the sound was not as iconic as with the previous V8s and V10s.

The issue slowly faded away though and, as the power of the current engines has ramped up, so too have F1 fans got used to the noise.

The 2026 power units are not going to feature a return to the old-era sound, but there should be a slight improvement based on the fact that the removal of the MGU-H takes away a little of the back pressure on the engine.

However, it must be remembered that the combustion engine will be burning less fuel than before. That means it will be working less in theory - so there will likely be a lowering of the noise.

Noise gains in one area, and losses in another, have left early pointers from dynos being that the 2026 power units do not sound much different to what we have right now.

And that means this element is unlikely to become much of a talking point.