Up Next

Sauber may be just 15 months away from becoming Audi’s works Formula 1 team, but the process of 'Audification' started back in 2022.

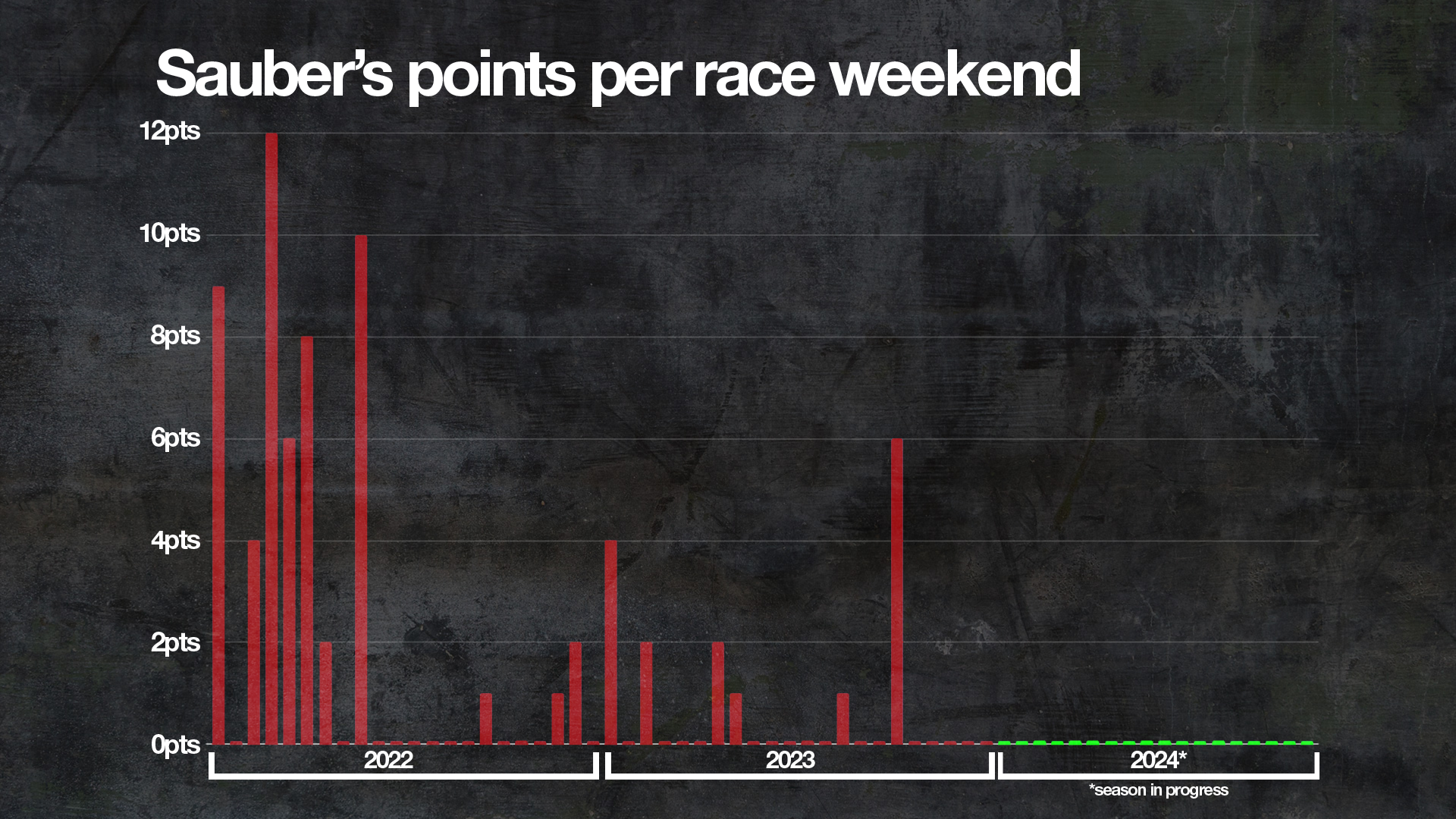

Not that you would know it given its dismal results. Sauber has failed to score a point so far this season, suggesting the team hasn’t heeded a lesson from the past when it was BMW's works team.

With just 16 points across its last 50 grands prix, this is a team that gives the impression it is drifting. But any expectation that Audi's illustrious record in other forms of motorsport - whether that's rallying, sportscars or tin-tops - and the prodigious investment level means success is guaranteed is misplaced.

The BMW Sauber era from 2006-09 is a cautionary tale that if you waste an opportunity in F1, which the Audi project appears to have done over the past couple of years when it should have been sharpening its competitive teeth with stronger midfield performances, it may never come again.

To tell that story, we must look back to the 2008 Canadian Grand Prix.

BMW on top of the world

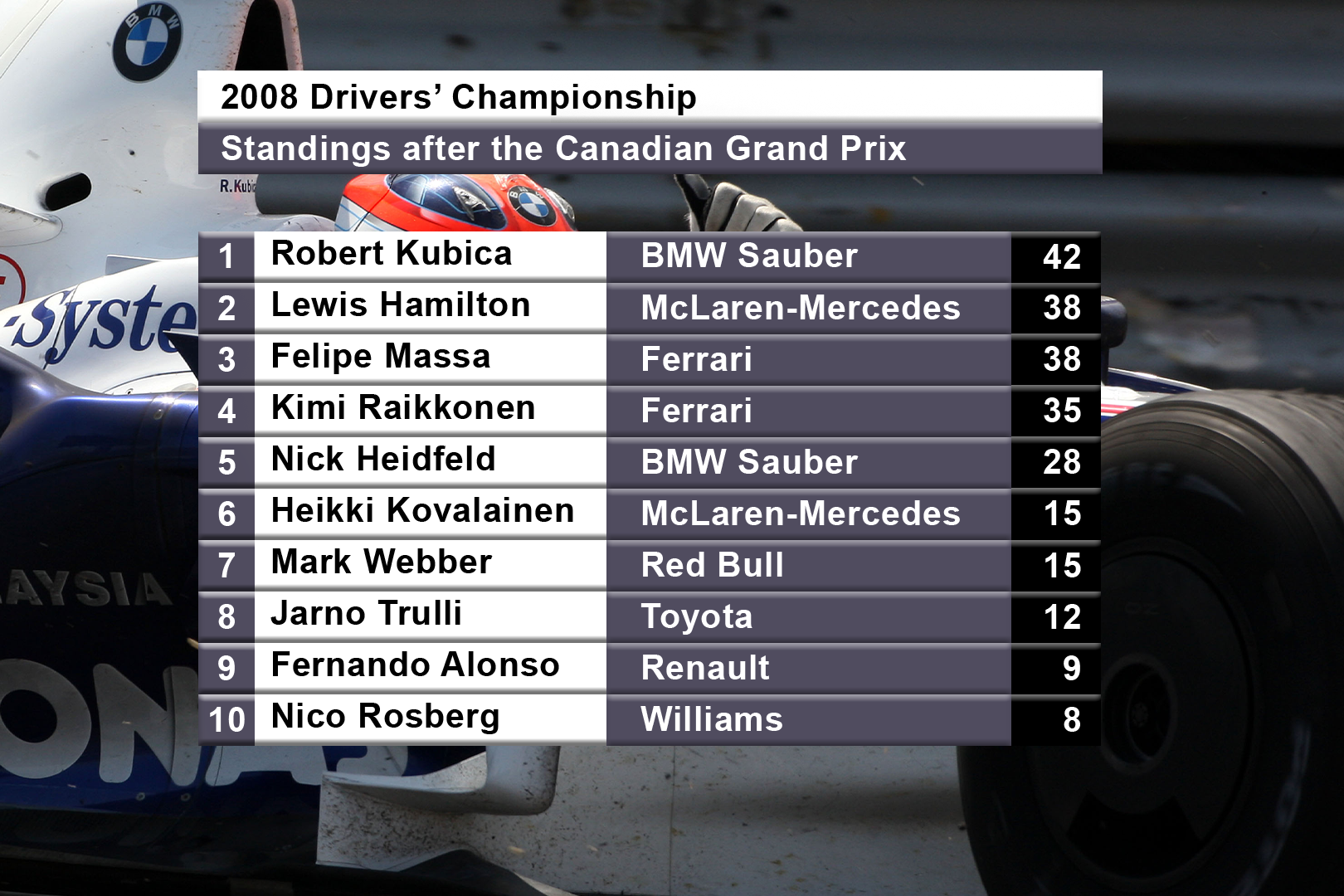

Robert Kubica took his only grand prix victory in Montreal in 2008, leading home Nick Heidfeld in a famous one-two for BMW Sauber.

That victory put Kubica into the lead of the world championship for the first and only time in his F1 career.

The BMW Sauber F1.08 was a seriously competitive proposition. While McLaren and Ferrari were a little faster, Kubica strung together a strong run of results including three podium finishes in the five races preceding Montreal.

The championship seemed on, but it ultimately never was - because it wasn't part of the plan. BMW had laid out a clear timeline for progress and that victory in Canada meant the box marked 2008 had been ticked.

This was the latest key step in a programme that had succeeded in hitting every target since BMW bought a majority stake in Sauber in June 2005. In the first season as BMW Sauber in 2006, the team finished fifth in the constructors' championship and bagged two podium finishes. It even exceeded the target set by team principal Mario Theissen.

"For our first year on the grid, we set ourselves the goal of both halving the 1.5-second per lap deficit to the leading cars, which the Saubers were running at in 2005, and improving on eighth place in the constructors' championship," said Theissen during 2006.

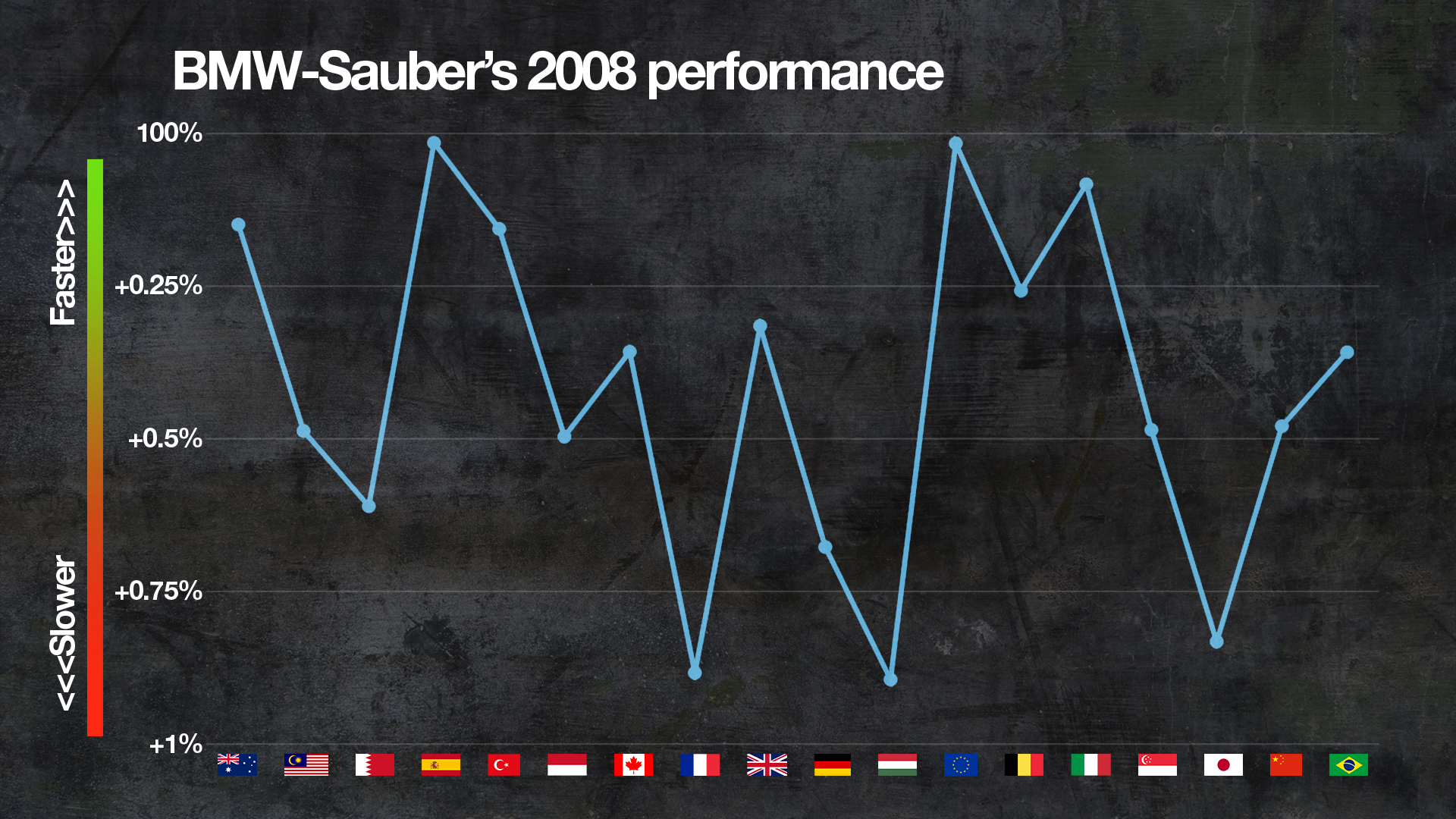

The pace gap target was even exceeded, BMW Sauber ending up just over 0.4% off on average - about four tenths over a 90-second lap.

In 2007, BMW Sauber did it again by climbing to second in the constructors' championship - third in reality given McLaren was excluded in punishment for the spy scandal.

It was felt that the team had also completed the necessary expansion and development to become a frontrunner.

"It is natural that expectations increase the more successful you become," said Theissen at the end of 2007.

"That brings pressure from the outside, of course, but also raises the standards we set ourselves. The end of this season has seen us wrapping up the development phase of the BMW Sauber F1 team.

"This phase has run according to plan and has seen us make it into the top three in a short space of time. Next year we will be looking to record our first win.

"We know that this will not happen automatically. The great progress we have made this year, in particular, has shown that we have got the direction of our development work and our working processes spot on. Motivation within the team is extremely high as a result."

A missed chance

Kubica and BMW Sauber had a genuine shot at the 2008 world championship. But with the first win bagged, as far as BMW's corporate strategy was concerned, the focus immediately switched to maximising development on the 2009 car.

That meant a drop-off in performance from having clearly the third-fastest car in the first part of the season to times where it was fourth, fifth, sixth or even, at its nadir, only seventh-fastest as 2008 went on.

The 2008 BMW Sauber was never the outright fastest car, even early in the season. But it was a strong car, a big step forward from the 2007 machine with what technical director Willy Rampf called "an aggressive development approach".

Early in the season, the car was capable of mixing it with pacesetters Ferrari and McLaren. While not quite as quick, it could battle with them - aided by Kubica's brilliance in a car that gave him the rear-end stability that suited his aggressive driving style. After a difficult first full season in F1 in 2007, he thrived.

He retired in Australia after being rear-ended by Williams driver Kazuki Nakajima, but that was followed by a strong run of results: second in Malaysia, third in Bahrain (after taking pole position), then fourth places in Spain and Turkey before a return to the podium with second in Monaco. Then came that win in Canada and everything changed.

In the remaining 11 races, Kubica only finished on the podium three times. Two of those came at Spa and Monza, lower-downforce tracks, with the final one a second place at Fuji that was assisted by a dramatic first lap that compromised McLaren's and Ferrari's races.

Even in that Japanese GP, against depleted opposition, Kubica led early on and drove a superb race yet slipped to second behind Fernando Alonso's Renault despite "a really great race" in a car he said "wasn't competitive anymore".

Kubica gave it his all, but the car simply wasn't quick enough. He ended the season down in fourth place, 23 points behind champion Lewis Hamilton back in the days of 10 points for a win.

That's a big gap and there's no guarantee that even with 100% effort BMW Sauber and Kubica could have done it. But it was a chance that was thrown away.

And it wasn't only a question of shifting focus to 2009. That was a perfectly understandable strategy given the dramatically overhauled aerodynamic regulations that were coming in. But BMW Sauber almost put the handbrake on.

According to Kubica, there were even components that were designed for 2008 that improved performance but never saw competitive action.

"In such a competitive sport, you need to use the opportunities as much as you can," said Kubica in an interview in 2014. "The train might go by once and you might jump on it and see what it brings, or you might stay where you are and maybe regret in a few years that it may have been better to jump on this train and see where it brought you.

"At BMW there was big focus on the 2009 car, big hopes with KERS, but in the end it was a big flop. The most difficult thing is that there were parts in the factory which were giving much better performance into the car but they were not introduced in 2008, they were waiting for 2009."

Theissen, who had strong disagreements with Kubica during the second half of 2008, saw it differently and strongly refuted the idea that BMW decided not to fight for the title.

He has stressed that there was actually more development during 2008 than in previous years. The team also had some windtunnel-to-track correlation troubles that played their part.

Regardless, the drop-off was stark.

BMW wasn't afraid of making its title aspirations very public, and as Theissen said, 2009 was all about fighting for the world championship.

"We are following a long-term timetable," said Theissen in March 2009. "In our first year we set out to finish regularly in the points, in year two we wanted to record podium finishes and in our third year we were aiming to notch up our first victory. We achieved all of these ambitious aims.

"In 2009 we are looking to take the next and most difficult step yet: we want to be fighting for the world championship title. The F1.09 gives us a good platform to fulfil this aim; now we have to see what happens in the season's 17 races. What we know for certain is that you can plan your level of performance, but not your results."

The accuracy of that final sentence was proved by how 2009 went.

BMW's decline and fall

The run-up to 2009 was encouraging for BMW Sauber. It was the first team to run a car broadly to the new regulations when it tested a 2008 car clothed in 2009 bodywork at Jerez in December.

It was an unsightly car, with the bizarre proportions of the snowplough front wing and narrow rear wing demanded by the regulations particularly grating. But it meant that BMW appeared to have stolen a march on the rest.

However, there were problems. One of those was of its own making through the introduction of KERS.

KERS - short for kinetic energy recovery system - was the first manifestation of hybrid power in F1. And BMW was very confident about the progress with its system, comprising a motor-generator unit and lithium ion batteries.

In fact, BMW was so confident that it blocked proposals from rival teams to defer the introduction of KERS. Theissen said in 2008 that "for various reasons, we could not accept postponement".

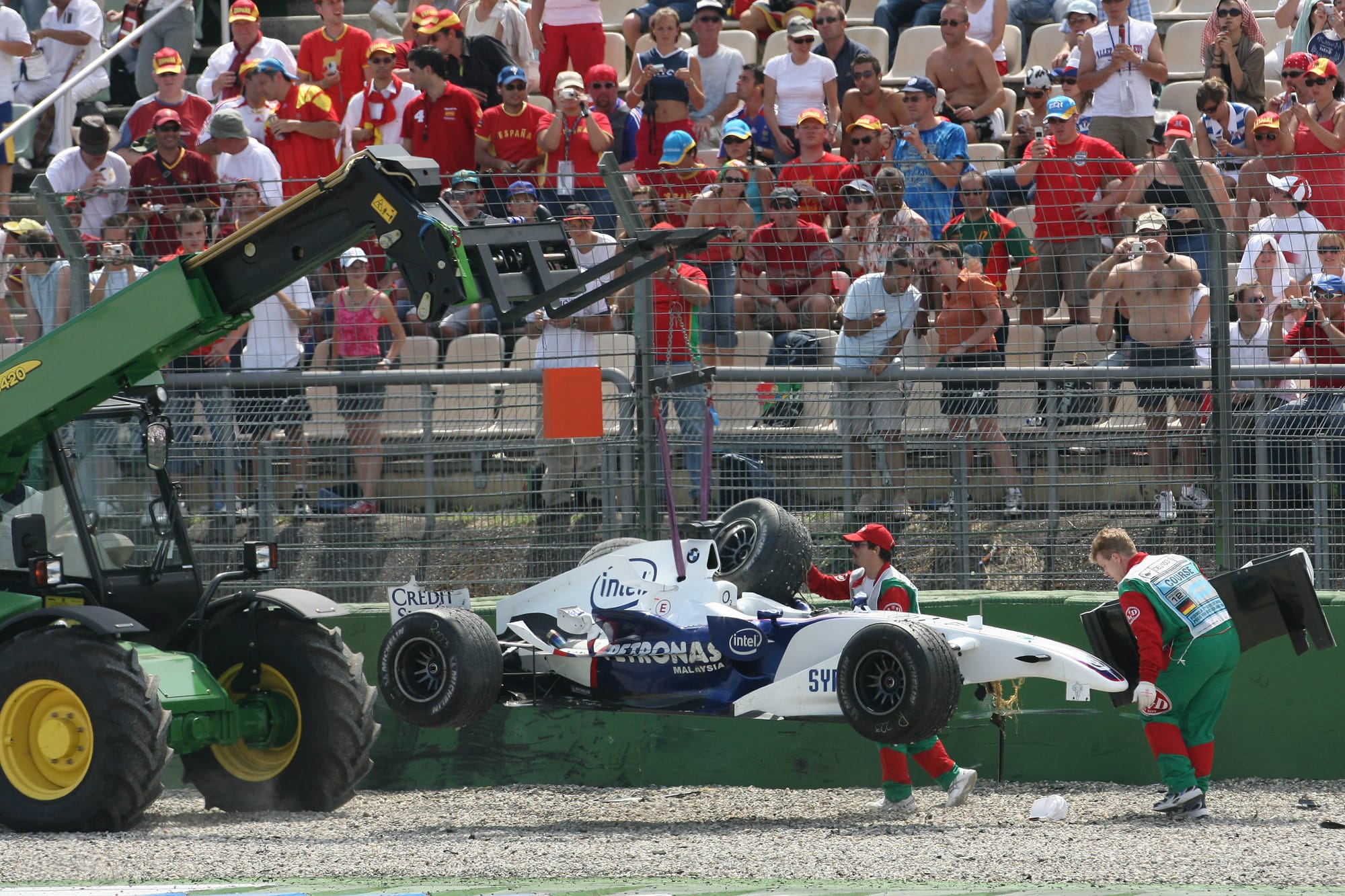

That was a mistake. There were high-profile problems with its development of KERS, such as the incident in testing at Jerez in July 2008 when a mechanic suffered an electric shock after touching the car when test driver Christian Klien returned to the pitlane.

But the big problem BMW Sauber had in 2009 was that its KERS was overweight and difficult to package. That was partly because of the air-cooled batteries, which had to be put in a place where the cooling airflow could get to them - with Rampf acknowledging that BMW Sauber "underestimated the complications and the impact they had on the car". There were also problems with the new wider front wings that it never completely got on top of.

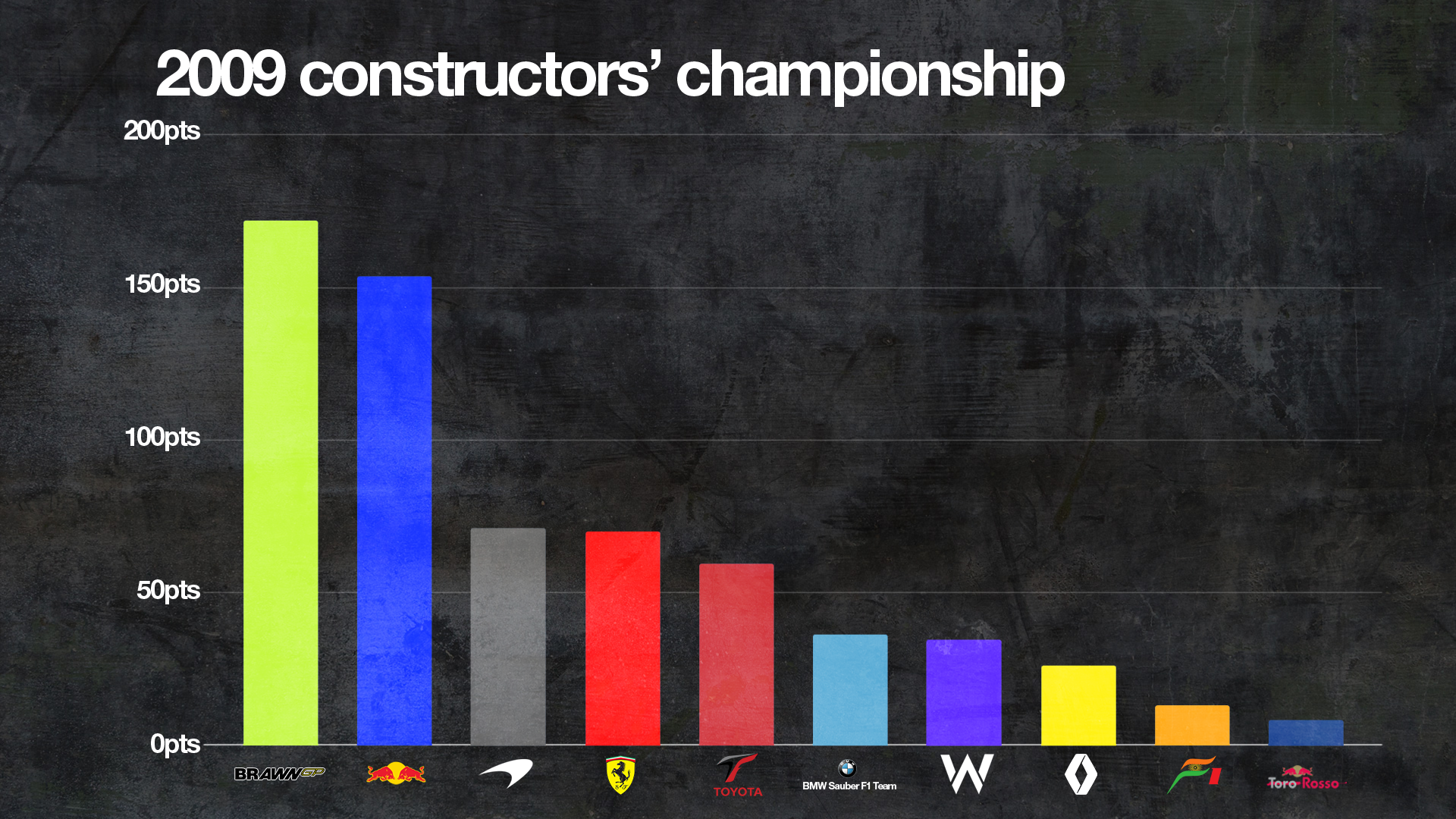

BMW Sauber also missed the double diffuser trick that Brawn, Toyota and Williams hit on. The team felt the double diffuser was illegal and Theissen argued it being ruled legal was a "gamechanger" that explains why the team failed in 2009. He cited the team's strong end to the season once a brand new gearbox had been introduced to create the space to optimise the double diffuser as proof of that.

The season started with Kubica's encouraging performance in Australia. Running without KERS because of his weight (Heidfeld did run it in the sister car), Kubica flew on medium-compound Bridgestones late on, only to be eliminated in a collision with Sebastian Vettel's Red Bull while battling for second.

But that race was a rare high point. Kubica finished second in Malaysia, with Heidfeld runner-up in the penultimate race of the season in Brazil, but results were patchy otherwise. KERS was decided to be a weight and packaging penalty that BMW couldn’t carry and it was dropped from the fifth race of the season in Spain onwards.

The team ultimately finished sixth in the championship, but by then BMW's F1 programme was doomed.

In late June, BMW made the shock announcement that it was pulling out of F1 at the end of the season as a result of the global financial crisis - or to use the official rationale, for reasons of "strategic realignment". Had results been as expected, perhaps things would have been different.

BMW's fourth year as a full works team went so wrong - after three years when it hit its targets admirably - that there was no fifth season.

This meant BMW's 10-year stay in F1, which started when it joined Williams as engine supplier in 2000, came to a dismal end.

And after various attempts to sell the team failed, notably to Qadback Investments, it was eventually taken over by founder Peter Sauber - who had owned 20% of the team throughout the BMW era.

Audi's lessons

So what lessons must Audi learn from this? Well, F1 is no great respecter of timetables and performance must be maximised at all times, with all opportunities taken.

It's not so much that Audi believes it has done enough over the past couple of years, as it seems not concerned that this time has been squandered.

Audi first committed to buying a controlling stake in Sauber in 2022. That takeover happened in phases, culminating in it upping its ownership to 100% in March 2024. The chance to have three full seasons of building up the team before it officially became Audi was rightly regarded as a fantastic opportunity. Without the pressure of the name, the team could expand both in terms of headcount and facilities, gradually working its way up the grid.

However, that's not paid off. Sauber has seemingly been treading water with the unstated view that everything will suddenly come together when it becomes Audi in 2026.

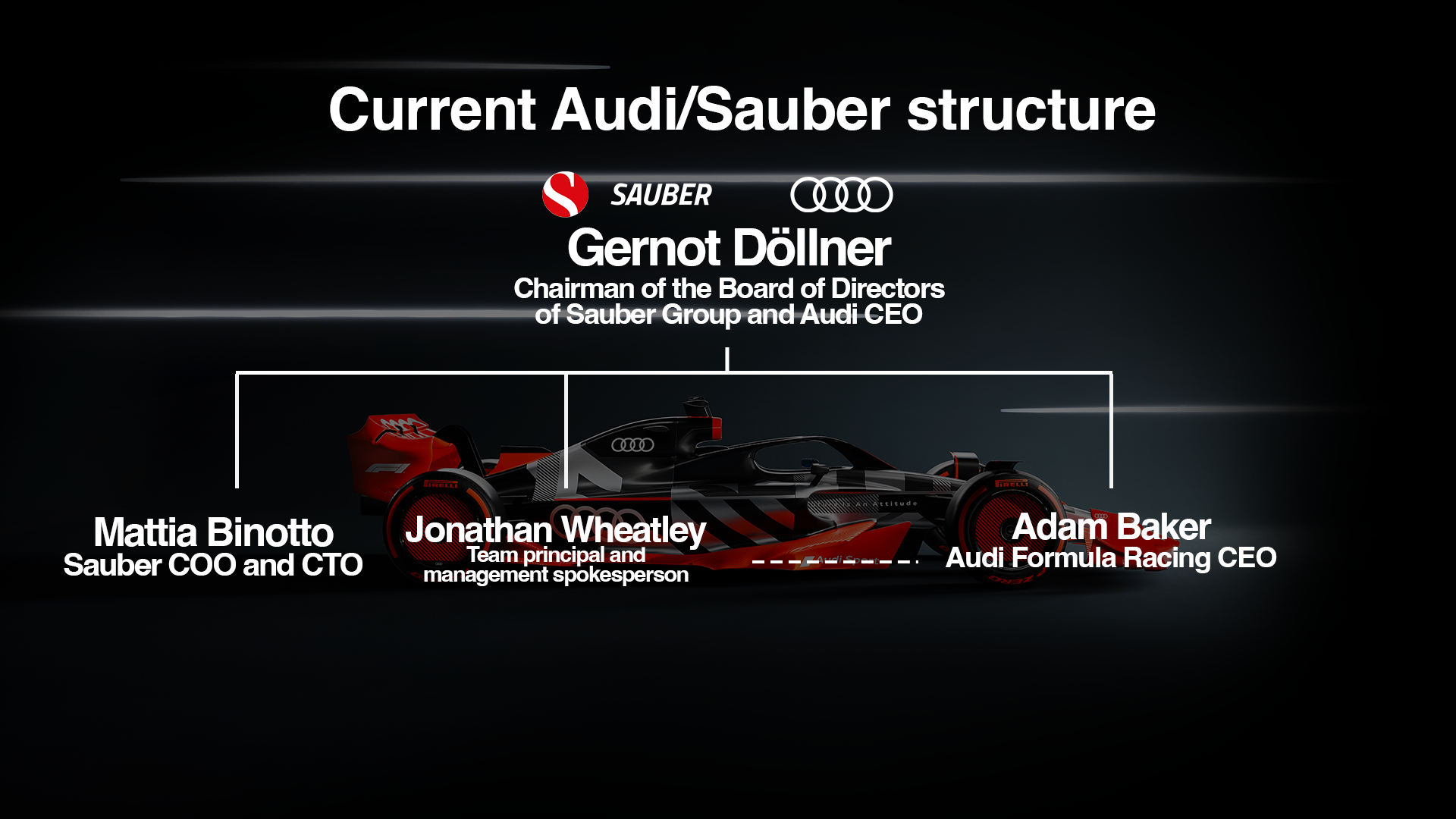

That's played a part in the recent shake-up, with ex-Ferrari team principal Mattia Binotto coming in as CEO. Red Bull stalwart Jonathan Wheatley has also signed up to join as team principal, but won't start until next summer.

Audi clearly has a plan but, in its BMW Sauber guise, this team made the mistake of assuming that things would come together in the future based on its own timeline. And it feels like at Audi, the same thing is happening again.

And Sauber now is far less competitive than it was in 2005 before the BMW takeover, so there's a very long way to go to get anywhere near the level of achievement of BMW Sauber's early years.

This is F1 and Sauber must maximise the next 18 months before Audi's debut. It needs to become a sharper racing organisation, improve its development rate and exhibit the ruthless pursuit of results any F1 team needs to have even a chance of getting to the front. As Binotto recently said: "We need to train our muscles for the future."

He's absolutely right. After all, in F1 if you work on the basis of success coming at some point in the future without being aggressive enough with short-term objectives, then tomorrow never comes.

Just as that glorious championship-winning tomorrow never came for BMW Sauber.