Up Next

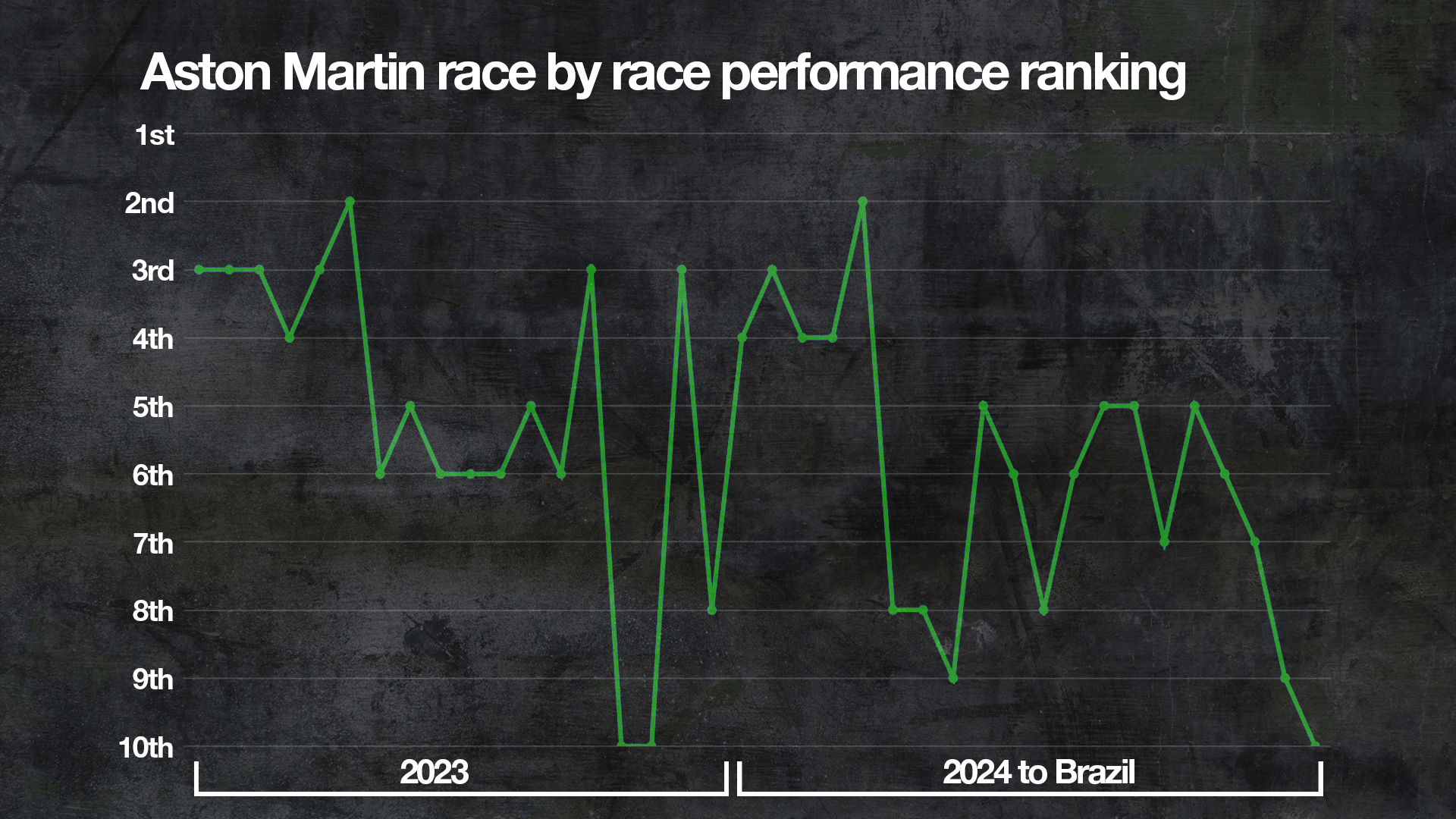

Few would have imagined, even when the peak of Aston Martin’s stunning podium-laden start to 2023 had long since passed, it would have the slowest Formula 1 car at some point in 2024.

As the mirage of Aston Martin’s brief stint as F1’s second-best team faded through last year, senior figures remained pragmatic but optimistic.

They knew the team had done a good job over the winter to bring together ideas from the people it had recruited from various teams, and had a solid base for 2023, but benefitted most from how much others slipped up and thus slotted into the gaping chasm between Red Bull and the rest.

They were keen to remain calm in the face of a downward trajectory because the reality of last season meant other, bigger teams should have been ahead of them and while it was disappointing that it faded the way it did, realistically, it was still a good season and potentially a strong foundation to build on further.

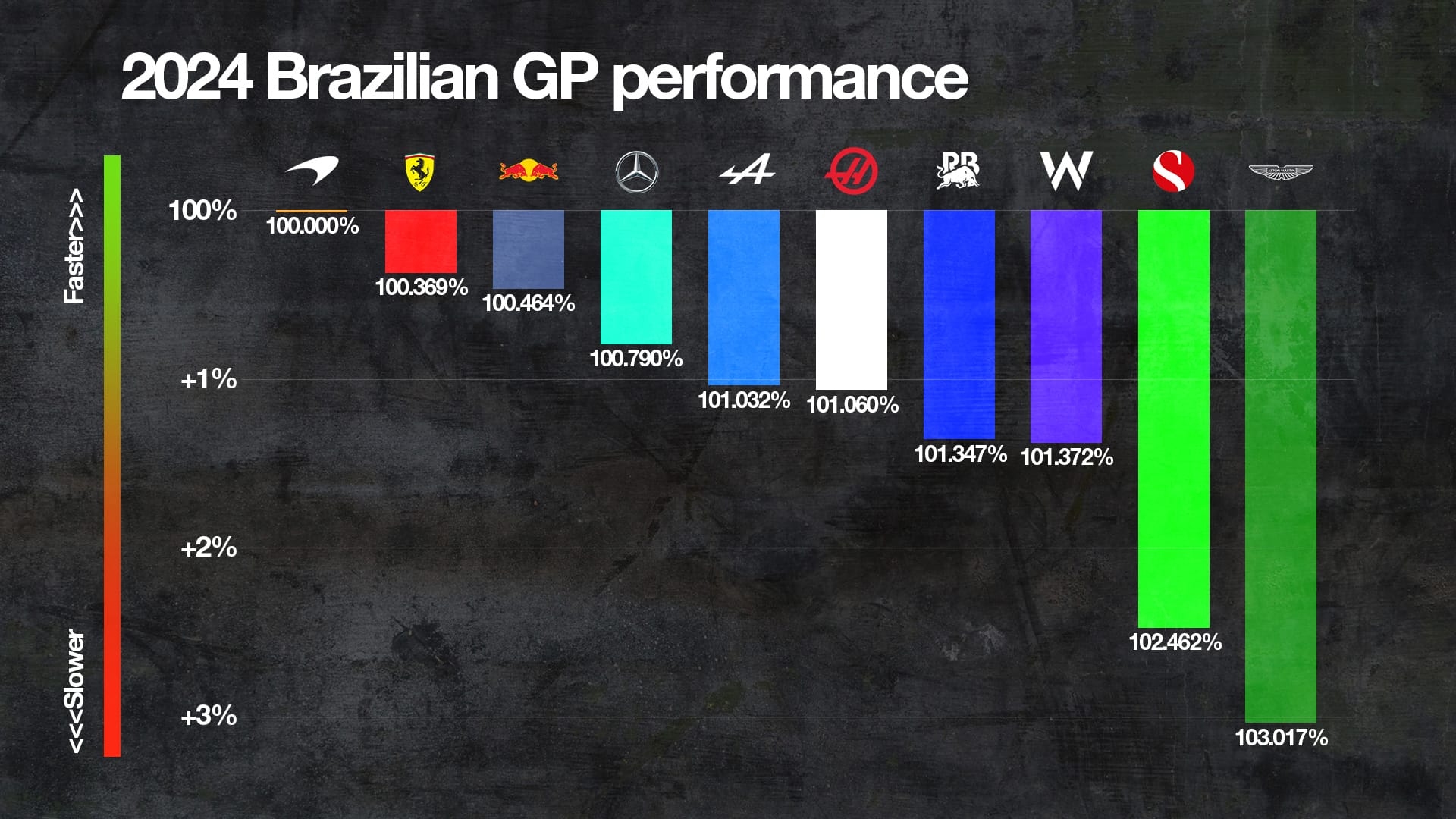

That has not happened in 2024. Its decline since has been persistent and is best illustrated by having the slowest car at the 2024 Brazilian Grand Prix, just 12 months on from its most recent podium finish - although the reality of that podium was more an opportunistic, well-executed race weekend by Aston Martin and some Fernando Alonso heroics than the car being genuinely that fast by the end of 2023.

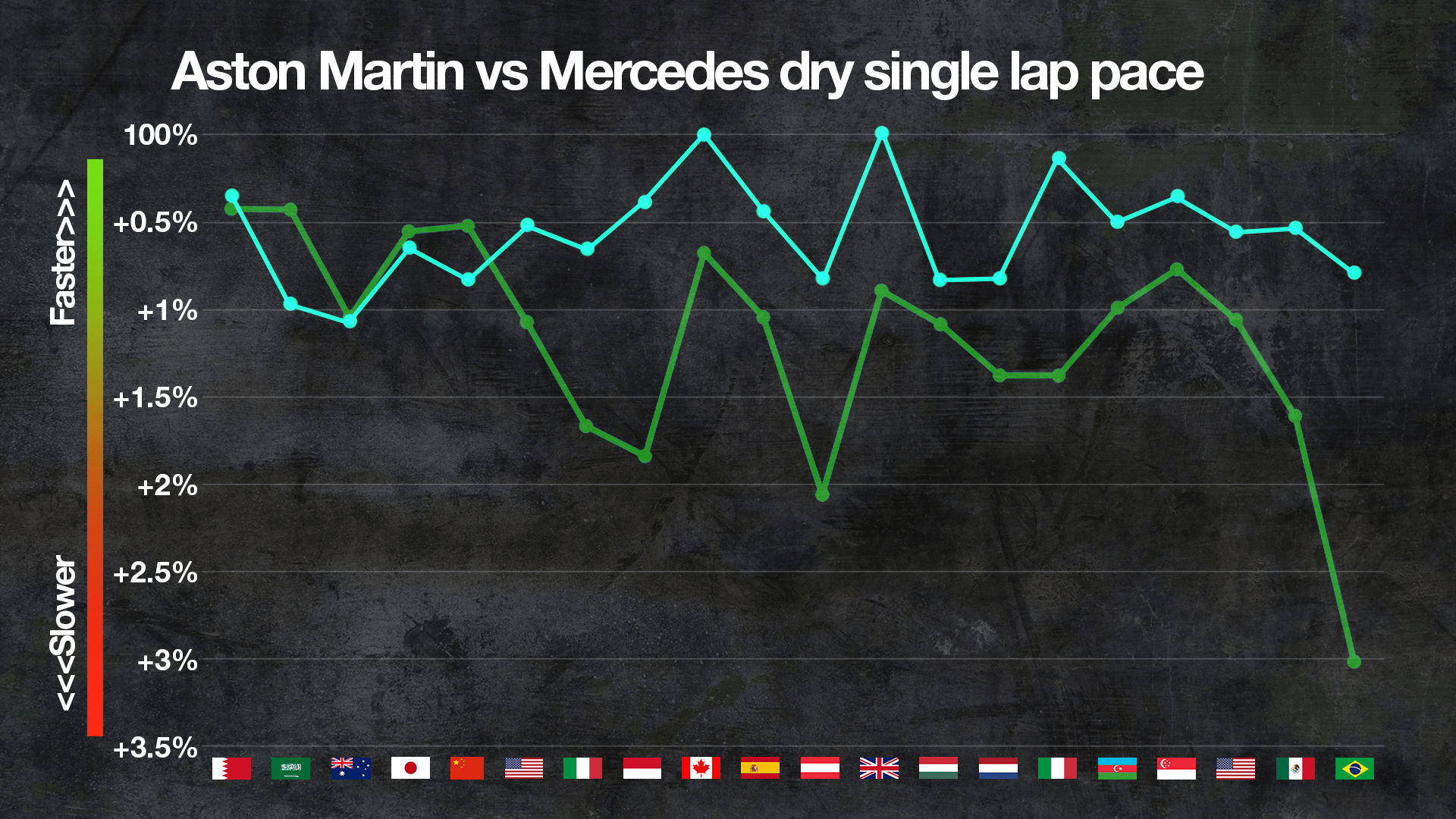

This year, having raced Mercedes in several of the opening grands prix, Aston Martin has slipped further into the midfield battle on a race-by-race basis.

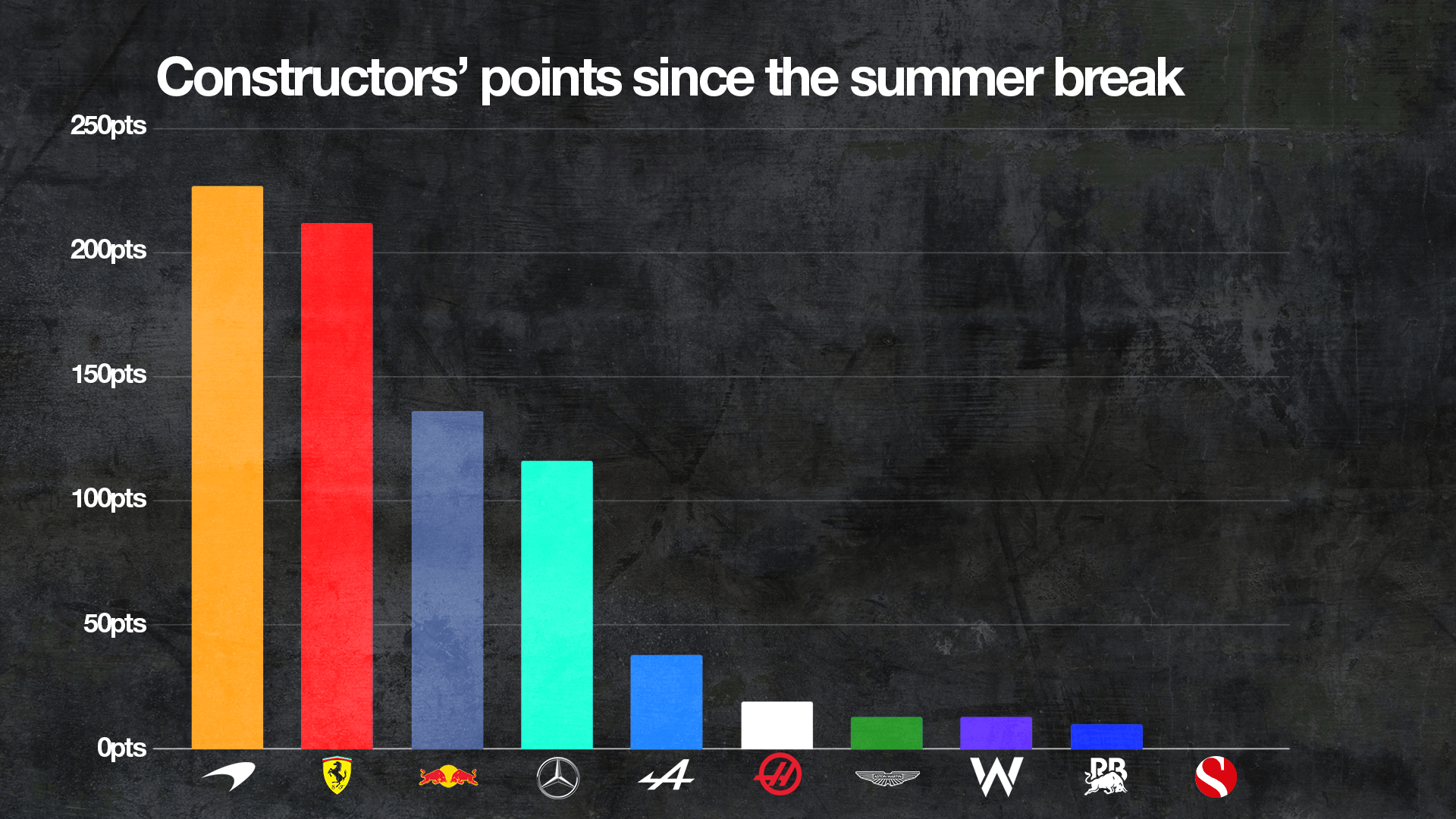

The majority of its points were scored in the first nine races and a point-less triple-header means Aston Martin has now scored just 13 points since the summer break: fewer than Alpine and Haas, level with Williams, and just three points more than RB.

Unsurprisingly it has often been slower than all of those teams at different points and most embarrassingly of all was even worse than Sauber in Brazil. That was partly exaggerated by circumstances but still marks the nadir of Aston Martin’s underwhelming season: set-up problems, floor spec changes, qualifying crashes for both drivers, an embarrassing formation lap exit for Lance Stroll and a futile race for Fernando Alonso, who finished between the two Saubers.

The floor issue was particularly telling. Aston Martin has been mixing and matching floor specs all season and started the Brazil weekend intending to use an older floor from race four in Japan then ended up running another older floor from Hungary in mid-season.

The fact it was not using its most recent floor upgrade from October’s United States Grand Prix is indicative of the development problems it has had. One race before Brazil, in Mexico, Stroll had declared: “I don’t think we’ve made the car quicker since race one of the season.”

That was an oversimplification. F1’s a relative game, as Aston Martin performance director Tom McCullough likes to say, so the AMR24 is probably better now than it was in Bahrain. But others have improved more, so the (relative) pace is weaker – leading to frustrations from its drivers and almost certainly pressure from the notoriously impatient chairman and owner Lawrence Stroll.

Corrective action is clearly needed and Dan Fallows no longer serving as technical director means at least some alarm bells are ringing somewhere inside Aston Martin’s impressive new factory.

Observing where Aston Martin has been weak is a lot easier than fixing it. Adding peak downforce is easy in the ground-effect era. But controlling the airflow effectively and using that downforce in different speed ranges without inducing problematic car traits has become a major challenge.

“It's very easy to set the targets, it's hard to actually achieve them without introducing other problems,” says McCullough.

That’s been a fundamental weakness of Aston Martin’s. Its development processes, its tools, or the way they're being used, have stopped it from bringing together the mechanical and aerodynamic platforms as effectively as other teams.

Whatever path Aston Martin chose developmentally for this car was wrong. Bodywork changes, front wing updates and floor revisions are just fiddling around the edges of a flawed concept. And the technical team in its current form has not been capable of tapping into the potential that exists in these rules, leaving it to hit up against the same development ceiling, rolling out mostly ineffective upgrades that induce negative handling characteristics.

In unsuccessfully chasing better medium and high-speed performance, Aston Martin has accidentally thrown away the good foundation it had in 2023 with a stable car that gave the drivers confidence and was particularly strong in low-speed corners.

But it also seems Aston Martin has prioritised the quantity of upgrades over the quality. If so, a bizarre and inefficient strategy at the best of times is simply out of touch with the demands of modern F1 when deployed in the cost-cap era.

The bottom line has been a car with no real strengths, lots of problem areas to troubleshoot, and futile development avenues that might actually have led somewhere if they had played out in full but were presumably cut short to get a physical part on the car.

A silver lining for 2025 is that Aston Martin feels that there are significant gains in the windtunnel that haven't made it onto this year's car, as they are being fed into next year’s. Waiting may be essential, if wider conceptual changes are coming. Or it could be evidence of the team learning its lesson not to rush things that aren’t finished yet.

But it is important that whatever Aston Martin is able to get right in 2025 doesn’t just repeat the cycle of developing well with a good lead time for a new season and then slipping back once it begins. Especially as 2025 will mark the arrival of two major recruits: Enrico Cardile as chief technical officer and Adrian Newey as technical managing partner.

Such arrivals are the elephants in the room where Fallows is concerned. There are two people already slotting in above where he was in the food chain, and that’s without factoring in Andy Cowell recently arriving as Group CEO and Bob Bell joining earlier in 2024 as executive director - both with much wider remits than the day-to-day technical leadership.

It was only a matter of time before a major reshuffle occurred to work out how to conceive a structure that works with so many senior figures. A top-heavy hierarchy has the potential to generate clashes of ego, inefficiencies, confusing lines of reporting and bad communication.

Even if that’s avoided, you still have the problem of the structure having to change to accommodate new people - and that means the previous leaders, like Fallows, being faced with the prospect of working in a set-up they didn’t sign up for.

It was made clear when Newey was announced that the technical organisation would need a new structure.

Given the extent of Aston Martin’s struggles, the quality and stature of the people joining, and the immense potential this project still has, it would be a surprise if Fallows’ F1 exit isn’t followed by further high-level changes.