As is the case every year, the Automobile Club de l'Ouest and the FIA have reviewed the way the World Endurance Championship's Balance of Performance is established. Only this year, they've done more than just fine-tune it.

And for many specialists, the concept, pushed a little further to the extreme each time, is starting to hinder the sporting side of the WEC.

What is BoP for?

The adopting of BoP in the Hypercar class caused a lot of talk, in the paddock and elsewhere. Used for many years in GT racing, it consists of a series of technical adjustments, primarily affecting weight and power, that are designed to create a level playing field among cars of different design and architecture.

BoP therefore helps maintain a similar level of performance between all cars, which reduces development costs significantly.

"In GT World Challenge, both because of the diversity of the cars accepted and the more marketing-oriented side of the series, it's understandable. But here, we're talking about a world championship," a competitor that knows both series well told The Race.

But why make such a decision for what is now arguably the second-most important championship after F1?

"The idea was to completely change the philosophy of the top class [compared to LMP1] and to design a new one taking into account all the different parameters of the moment," explained Marek Nawarecki, FIA circuit sport director, in 2023.

"One of them concerned the costs, which were very high. The adoption of the BoP, allows us to have less expensive cars. It is indeed one of the only ways to slow down the development race, as manufacturers know that the cars will be balanced with each other."

How does BoP work?

"The BoP compensates for the equivalence between two-wheel drive and four-wheel drive [cars], aerodynamic performance, differences in centre of gravity, refuelling time which depends on the amount of energy on board," explained Thierry Bouvet, ACO international technical delegate.

"What it will not do is compensate for a lack of optimisation in the race: the competitors are responsible for the drivers' form, strategy and tyres. And neither will it compensate for a lack of performance if we do not have enough representative data."

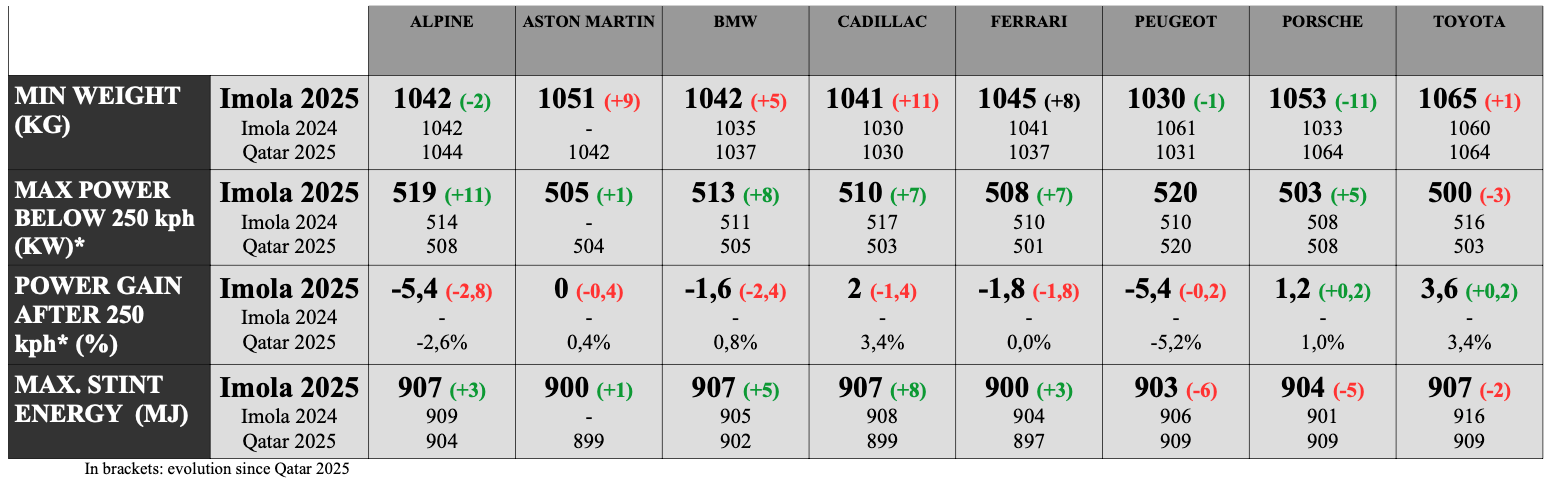

Therefore, the figures appearing in the tables are the result of three parameters: the homologation parameters, the platforms equivalence and the manufacturer compensation. Before going any further, here's a brief explanation of each of them that Bouvet gave us at the beginning of 2024.

Homologation parameters

"They are based on information gathered in the windtunnel, the centre of gravity, the average amount of fuel on board, etc. All this data, combined with that gathered on the tracks, allows us, thanks to our simulation tools, to define these approval parameters."

Homologation parameters necessarily evolve with each race since they depend on the tracks: "The aerodynamic performance of the cars is evaluated in a windtunnel, and once they are within the performance window, we freeze them and scan the car. These data become our reference."

Platforms equivalence

"We balance the best LMH [a car 100% designed in-house] with the best LMDh [a car based on one of the four approved chassis manufacturers, and equipped with a standardised powertrain]. We want both these platforms to be able to win."

Manufacturer compensation

"We have seen significant differences in performance between two cars from the same team," explained Bouvet at the beginning of 2024. "From now on, we will base ourselves on the average of the best cars from each manufacturer."

This will define the level of performance to be achieved. The governing bodies then take action if a competitor needs to be slowed down or to be given a boost.

How did the BoP work in 2024?

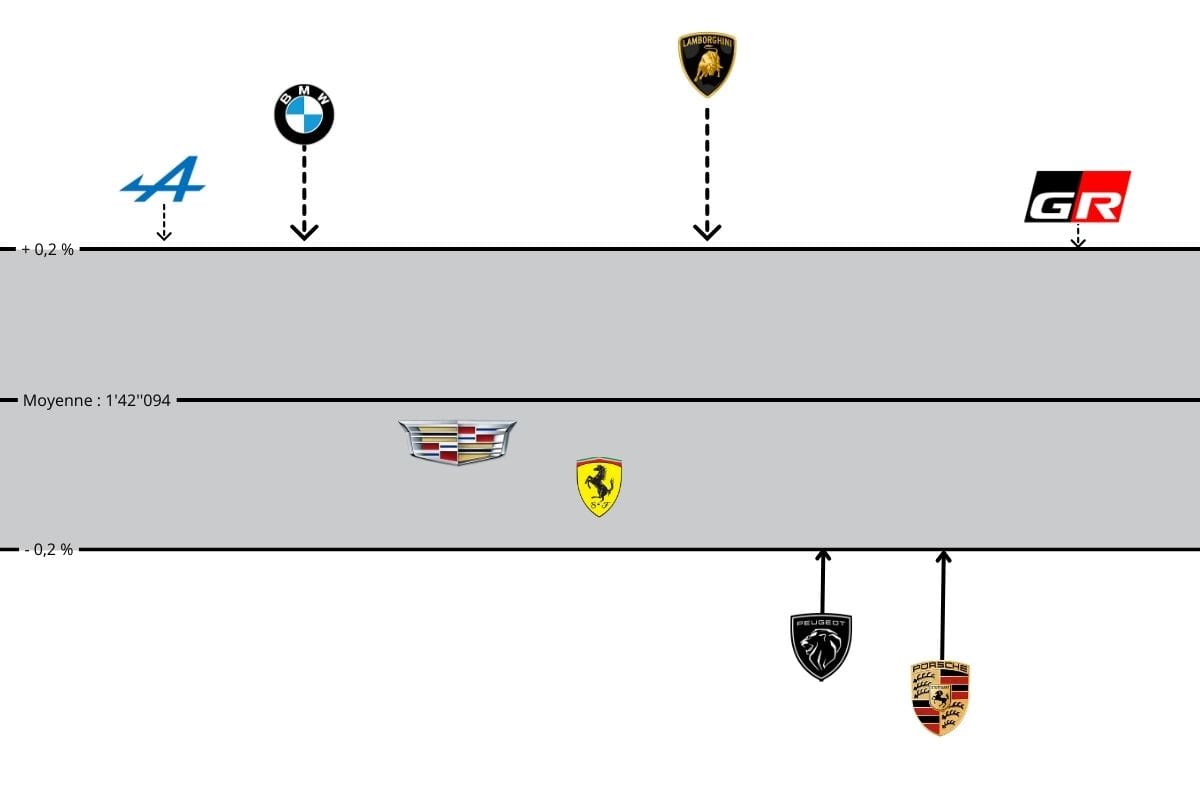

Last year, the ACO/FIA defined a performance window in which all cars should be in an ideal world. "We establish it to determine whether or not a manufacturer needs compensation," we were told.

The upper and lower limits of the window were 0.2% above and below this average of established performance, resulting in a very narrow window, only 0.4% wide. For this purpose, 20% of the best laps in the race were selected.

Below you can see an example of what this window looked like.This one was the one from Qatar, a race that was clearly dominated by Porsche and Peugeot.

"The idea is that all the cars are in it [the window]," explained Bouvet. "And if that's not the case, then we need to put back the ones that aren't, one way or the other. If everyone is in it, then it's perfect. If not, then we take action."

Indeed, the manufacturer compensation parameters of those in the window were not modified, and it was up to the teams to work to get as close as possible to the lower limit. A highly commendable ploy that leaves room for meritocracy.

Until the Le Mans 24 Hours, only the most recent race was used to establish the manufacturer compensation parameters. But subsequently, a decision was made to opt for a rolling BoP based on the last three races. In addition, a dual stage BoP was also adopted starting with the Le Mans 24 Hours, with a power level modification above 250 km/h to level out the top speed of the different cars.

And at the end of last season, the BoP was quite good with very close performances. But despite this, the decision was taken to change the philosophy adopted again to tighten up the performances even more.

What's changed in 2025?

Here we are: 2025, a highly anticipated season, the second round of which is being held this weekend in Imola. First of all, it is important to know that this evolution of the system is the result of eight technical working groups organised during the winter with the FIA, the ACO and the manufacturers.

"It is an evolution of the process. We are doing it in a slightly different way," Thomas Chevaucher, FIA technical engineering director, explained in Qatar at the end of February. "All the parameters we implemented offer nice competition. They don't compensate for strategy, tyres and driver performance. The target is to balance the potential of the cars."

But specifically, how have the calculation methods changed?

"Last year we took the average of the 20% best laptime," Bouvet recalled. "Now we use a combination of the 10 best laptimes and 60% best laptimes average, so it is more race representative."

By basing the parameters of manufacturer compensation on only 20% of the best race laptimes, the legislator only considered laps completed on fresh tyres.

But 60% of the best laps in the race is a big change from the past. Whereas second-order performance parameters such as tyre degradation were not taken into account, they are now.

"That was a wish," Bouvet confirmed. "There are still slight differences between LMH and LMDh so we needed to take into account more laps to remove these small differences. It was very collaborative with all manufacturers, we tried many ways to open the eyes of the manufacturers and took their feedback into consideration."

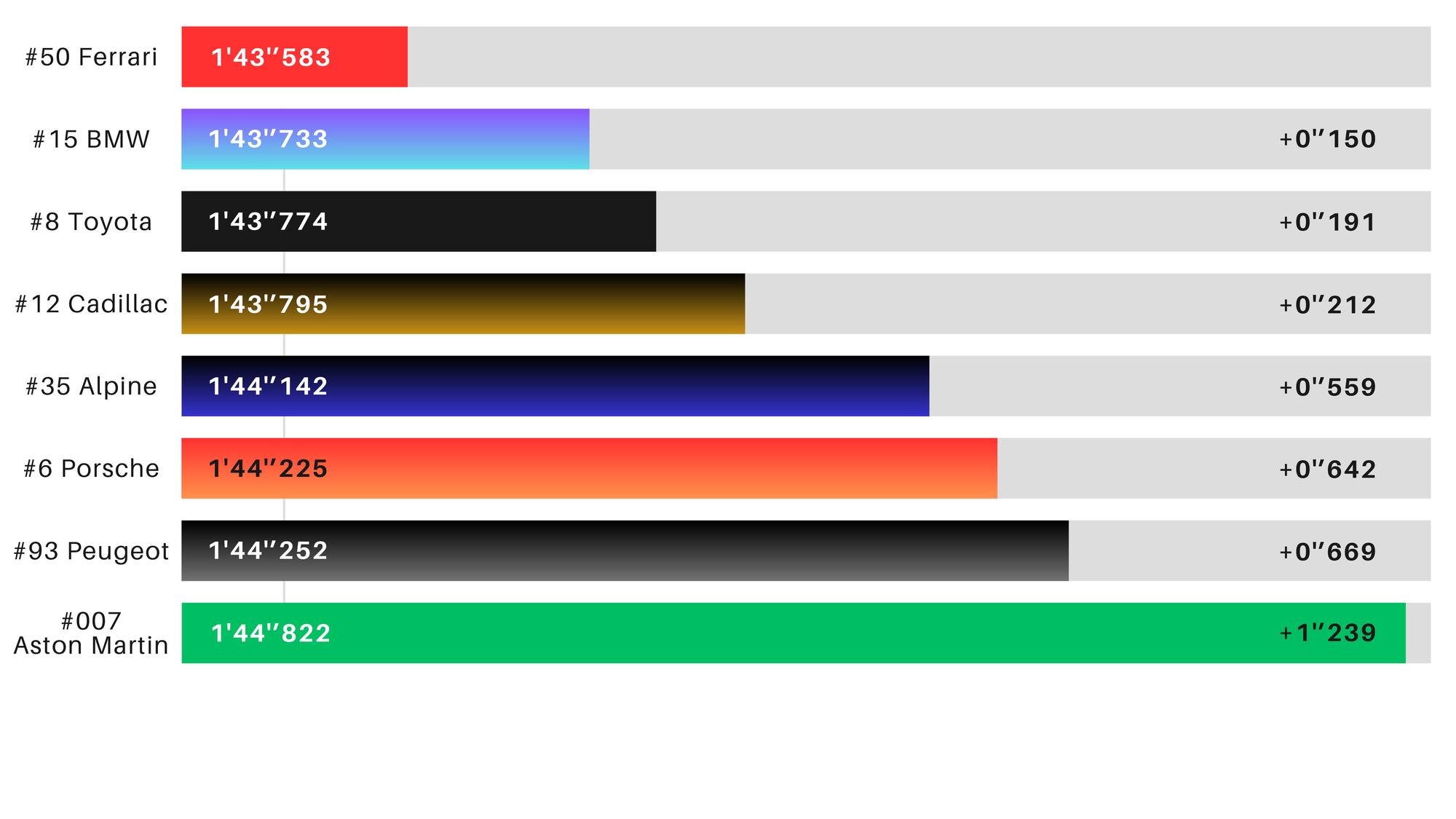

To give you a clearer idea, below you will find the classification of the 60% of the best laps in the race during the 1812 km of Qatar.

All this without forgetting that the BoP is rolling, and that the data used are those of the last three races.

To arrive at the figures for Imola this weekend (see the table below), the FIA and the ACO have therefore used the average of the 60% of the best race laptimes as well as the 10 best laps in the race of last year's Fuji 6 Hours and Bahrain 8 Hours, plus the Qatar 1812 km 2025.

The system is the same in LMGT3, with the difference that the 10 best laps in the race are not taken into consideration because the category mixes professional drivers and gentlemen drivers.

But by taking the average of 60% of the best laps in the race, we also balance the drivers against each other in a way. In the end, the number of parameters taken into account only increases and this is confirmed by the next point discussed: 100% convergence.

What is 100% convergence?

Last year, as explained above, the different cars had to be within a 0.4% window. This year, the philosophy has changed, as the governing bodies want all the cars to be able to achieve exactly the same laptimes. We are obviously talking here about theory and potential of performance.

"We are targeting 100% convergence on laptime," Bouvet explained. "Last year, in the Hypercar class, it was not a full compensation. Once more, there's still some differences between the LMH and LMDh about components which can have an effect on the tyre deg."

He is referring to the advantage that LMHs with a MGU connected to the front axle could have over braking zones and in acceleration phases. Confirmation if there was still any need for it that cohabitation between LMHs and LMDhs is not so easy.

What about a new car?

As the manufacturer compensation is based on data collected during the last three races, how can a car that is starting in competition be balanced, as was the case with the Aston Martin Valkyrie in the 1812 km of Qatar?

"We consider the best in the class for the last three races," Bouvet confirmed. "And for good reason, we have no data. And then gradually this car will come into the process."

At Imola this weekend, the data used will therefore be that of the best cars at the 2024 Fuji 6 Hours and the 2024 Bahrain 8 Hours, and that of the Aston Martin at the 2025 Qatar 1812 km.

Le Mans is a special case

Due to the nature of the track and the importance of the Le Mans 24 Hours, the BoP in force there is unique. Just as it will not be taken into account when establishing the BoP for the Sao Paulo 6 Hours (July 13), which will instead be based on data collected in Qatar, Imola and Spa.

"Le Mans is outside the process," Chevaucher confirmed. "It's not necessarily based on the WEC races. This Le Mans process is as it was done last year."

Uncertainty still reigns as to the system adopted, but the governing bodies assure us that they will not rely on data from June 2024 to prevent a competitor from sacrificing one edition to perform well in the following one. Everything suggests that the calculations will be based solely or almost solely on data from the simulation.

As has been the case since Le Mans last year, a power variation will be made from 250 km/h to ensure that there are no excessive disparities in terms of top speed. That parameter will obviously be even more crucial at Le Mans than anywhere else.

What should we make of this?

If you've got this far and you haven't had to swallow an aspirin yet, we're delighted! The system is complex and difficult for the teams to understand, so imagine what it's like for us. But one thing's for sure, it's divisive. In fact, we can confirm that several protagonists have expressed their dissatisfaction to us. (But not on the record.)

Article 6.2.1 of the WEC sporting regulations stipulates that manufacturers, competitors, drivers and any persons or entities associated with their entries must not seek to influence the establishment of the BoP or comment on the process and/or the results, in particular through public statements, the media and social networks.

By taking into account the average of the 60% of the best laps in the race, the governing bodies cancel out completely or almost completely any advantage that a car might have had in terms of tyre degradation.

Second-order performance parameters are now taken into consideration when establishing the BoP, and this is highly regrettable. To a certain extent, even the performance level of the drivers is balanced, especially in LMGT3, where professional drivers and gentlemen drivers are mixed together.

"The BoP does not compensate for the strategy, the choice of tyres, the form of the drivers and so on..." Chevaucher insisted. Until now, the governing bodies have always defended themselves on the basis that this had to remain a sport.

Today, what will make the difference on the track is only the drivers and the strategy, even if there is less room for manoeuvre than in the past, particularly with regard to fuel consumption and tyre management. But it is clear that the competition is no longer in the design offices. Engineers must be bored...

This leaves us fearing a levelling down and reminds us of a sentence uttered by an individual from Peugeot Sport at the very beginning of the 9X8 programme: "If we are behind, the BoP will take it upon itself to raise us to the level of the others."

Moreover, last year the BoP showed its limitations, and this should be the case again this weekend at Imola. By making the Toyota heavier and reducing its power level, the car no longer has any raceability. Because of sluggish acceleration, the GR010 Hybrid drivers are no longer able to overtake or defend themselves on the track, and the most striking example remains the 2024 edition of the Lone Star Le Mans in Austin (Texas).

Sixth on the grid, the #7 Toyota surprisingly found itself on course to win (it ultimately finished second). But the car never overtook any of its direct rivals on the track - only managing to take the lead through daring strategies, particularly undercuts. So it gained the upper hand thanks to its strategists, but also because the car managed the tyres better than its rivals. An advantage it will no longer be able to count on this year.

If we can understand that there's still some differences between the LMHs and LMDhs about components which can have an effect on the tyre deg, Toyota, which still has the best racing team in the field, is clearly the big loser under this new BoP system.

Narrow aero window, centre of gravity, downforce/drag ratio, top speed...everything is aligned, including the stint length and the time spent at the pump.

Indeed, the efficiency of the engines is very disparate, particularly between the very old twin-turbo V8 of the Porsche 963 (derived from that of the RS-Spyder) or the V12 of the Aston Martin Valkyrie and the efficient twin-turbo V6 of the Toyota GR010 Hybrid. The cars therefore start with a different amount of fuel - but that too is compensated for.

So our concern is twofold. First of all, isn't tyre management part of the DNA of endurance racing?

How can we forget those splendid battles between Porsche and Toyota in 2017, when the TS050 Hybrid relied on its ability to keep the same tyres for two stints to compete with a 919 Hybrid that was faster on one lap but very aggressive with its tyres.

And how many cars have won the Le Mans 24 Hours because it consumed less fuel than its rivals, completed one more lap per stint and therefore saved itself trips to the pitlane? That was also the magic of endurance racing!

Moreover, by aligning the cars on all parameters included the top speed, won't we end up with pack racing? Overtaking will become increasingly complex, as we saw again in Qatar, on a circuit that - it must be said - is not very conducive to overtaking either. Should the show take precedence over the sport?

But regulation is judged by the number of competitors on the track. And without this BoP, there wouldn't be as many.

"Think back to where we were four years ago," President of the FIA Endurance Commission Richard Mille said in November 2023. "In both Hypercar and GT classes, we have grids like we've never seen before. Nobody believed it."

This year there are eight manufacturers in Hypercar, and they will be joined by Genesis in 2026 and then Ford and McLaren in 2027. And it is worth remembering that between 2018 and 2022, Toyota was alone against private teams.

So if the rules of the sport seem to be flouted, how can the promoter be proved wrong?

Despite these regulations based on the BoP, which go against all the fundamentals of motorsport, endurance racing has never been in better shape.

The general public, some of whom will be scarcely aware of the BoP, are delighted. The purists are much less so...